A new book by Nordic scholar Matthias Egeler looks at the otherworld.

The wicked fairy in fairy tales, the elves in Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”, Princess Lillifee and her friends: fairies and elves are common in literature. Professor Matthias Egeler, an expert in Old Norse at Goethe University Frankfurt, has written a book about them. In “Elfen und Feen. Eine kleine Geschichte der Anderwelt” [“Elves and Fairies. A Brief History of the Otherworld”], Egeler traces the links from the cultural history of Celtic and Nordic myths to today’s pop culture, and explains the nature of these mythical beings, which is by no means always angelic. Some of them can definitely get rough and tough if they feel threatened.

UniReport: How did you come up with the idea of writing a book about fairies and elves?

Matthias Egeler: Fairies and elves are important phenomena in European cultural history. We all grow up with these stories – from the fairy in Pinocchio’s story to Tinker Bell in Peter Pan. We’re familiar with this diverse parallel existence of multiple kinds of elves and fairies. Through this omnipresence, including the myths and literature of the medieval period, they also feature prominently in my work as a medieval scholar. The book is an attempt to trace the development of elves and fairies from the medieval period to the present day.

Do today’s forms have anything at all in common with the fantasy creatures of the Middle Ages?

If we juxtapose today’s forms and the old ones that are still with us, we initially gain the impression that one end of the spectrum has nothing to do with the other. But history has a very good explanation of how today’s parallel worlds with such different fairies and elves in literature, art and popular culture developed. What’s more, we can learn how cultural and religious history works: the history of elves and fairies illustrates the importance of interactions and contacts in European cultural history and the significance of adapting mythical motifs to new contexts.

Would it then be correct to say that every age chooses the kinds of elves and fairies it needs?

Exactly! Everything current is a reaction to contemporary needs. The fact that these needs keep on evolving gives rise to a variety of elves that satisfy these needs, in accordance with each place, time, social status and economic situation.

Fairies and elves originated in the era of myths and sagas, before Christianity arrived on the scene. People wanted to explain certain phenomena or events in their lives and created these tiny beings for that purpose. Incidentally – are all of them tiny at all?

That depends. Today these tiny elves have become an important strand in our image of elves. Small elves are first prominently mentioned in the 16th century – think of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Tiny winged elves first experienced a breakthrough among English artists and literati in the 19th century.

That sounds similar to the history of the Heinzelmännchen in Cologne, who helped the poor shoemaker in his workshop at night.

I must admit I don’t know as much about the Heinzelmännchen as I would like to. My area of research is Old Norse and Old Irish literature and the world of the Icelandic folk sagas. But yes, helpful creatures like these also feed into our ideas about elves and fairies.

So, elves exist in Germany only thanks to literary reception?

Yes; from a German perspective especially, elves are a wonderful example of the importance of cultural contacts for the history of religion. Elves are an invasive species in Germany. The word “Elf” entered the German language via the reception of Shakespeare in the 18th century. By contrast, the German word “Fee” [fairy] is a loan word from French.

Does this mean that elves and fairies are merely two different words for the same phenomenon?

Again, that depends. By and large yes, but in certain individual contexts it was recently discovered that the two concepts arouse different kinds of associations. In the 19th century, the motif of tiny fairies became established in literary and artistic circles among the urban elites. Not everyone liked this idea, as a result of which a countermovement soon developed within which Tolkien had the largest impact. In “The Lord of the Rings”, he reverts to the medieval notion of elves, who not only resemble but are also as big as humans. Thanks to his books’ success, elves once again became firmly established in the popular spectrum as powerful beings. Today it is this Tolkienian part of the spectrum that is more frequently associated with the word “Elf”. The word “Fee” – fairy – by contrast, is often found at the other end of the spectrum, i.e. tiny beings with insect-like wings. Juxtapose Legolas the elf and Tinker Bell the fairy.

But originally fairies and elves were the same.

From a purely linguistic perspective, one is a Germanic word and the other a Romance word for a concept that played an important role in medieval literature. What we actually have are two equivalent concepts that – depending on the context – can trigger different associations.

Does this differentiation also apply to contemporary popular culture, including children’s books about Princess Lillifee and the like? There also exist children’s books that present a different image than that of the twee, glittery fairy and instead describe elves as helpful domestic spirits.

In the history of literature, there has long been an awareness of widely differing types of elf. The idea that elves are offended if we call them fairies already found expression in Kipling’s “Puck of Pook’s Hill”, written well over 100 years ago.

You’ve already given five long interviews about this book on elves and fairies – an incredible response. Were you expecting that?

No, not at all. Five years ago, I published a book with the same publisher about the Holy Grail, which did not meet such a popular response. I was surprised at how popular the subject evidently is.

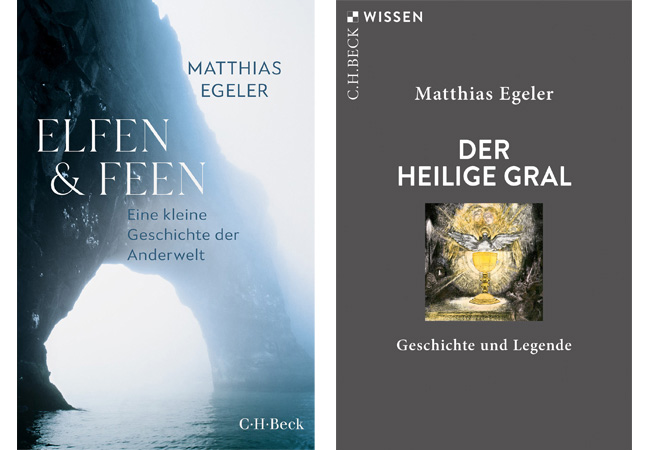

Elfen und Feen. Eine kleine Geschichte der Anderwelt

München: Verlag C.H. Beck 2024,

Matthias Egeler

Der Heilige Gral. Geschichte und Legende

München: Verlag C.H. Beck 2019

Given that there already are a large number of esoteric publications on the Holy Grail, maybe it’s more difficult to arouse public interest with a scientific book about the subject?

As a medieval scholar I don’t see much of a difference if I’m writing about the Holy Grail or about fairies and elves, as both subjects are part of the Arthurian tradition. I would have thought they would be of equal interest to the public, but life is full of surprises.

Why did you choose to write a “popular” rather than an academic book? Is there not much left to discover?

I can’t think of a single book about elves that tries to paint a bigger picture of the topic in this way. Given that elves and fairies are invasive species in Germany, there’s also much less written about them in German than there is in English. The situation in the anglophone world is totally different: there are many top-level scientific publications, which, however, all have different focal points. This means my book takes a new approach and provides added academic value. That being said, because I wanted to reach a broad public, I wrote a book for the layman. Had I wanted to write an academic book, I would have had to write it in English because the research discourse is very English-based; and these topics are much more present in English-speaking countries because elves and fairies have always been an important part of their literary tradition. Just think once again of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” An academic book in German simply wouldn’t find an audience. Nonetheless this is not a case of either-or, but of both, because Yale University Press is going to publish an English translation.

That means you’ve been knighted!

Yes, I’m very pleased about it. I enjoy writing for a broad public. First, it’s one of my tasks as a humanities scholar to conduct basic research, to examine things that might appear very obscure to outsiders. But I also consider it part of my job to make knowledge accessible to society in general. That’s what I wanted to do with this book on elves.

In your book you state that today’s elves generally have ties with nature, which was definitely not the case with the original elves. However, contemporary elves tend to be harmless. Would you like to see more aggressive elves?

That question does not concern me so much. If a book for a three-year-old present a more harmless image of fairies and elves, that’s absolutely understandable. I do have the impression that a rather sugary variation of fairies also prevails in books for teenagers and adults. This is not a criticism, it’s just that I notice an apparent need for these kinds of fairies and elves. All the same, I find it interesting that elves are now strongly associated with the environment and nature – which is in no way based on tradition – while simultaneously imagined as sweet and cute. I think this is a fascinating combination, and I’m not sure how we should interpret it. I would have expected that with more space in social discourse dedicated to the environmental crisis, ideas about nature spirits would be adapted and become more threatening. But maybe this will just take another ten years.