Political scientist Prof. Monika Oberle participated in the joint “Pilot Monitor for Civic Education” project. Speaking to UniReport, she explains the study’s key findings.

UniReport: Professor Oberle, the term civic education has become the subject of much more debate and controversy in these turbulent times than it was decades ago. As a scholar, can one (also) be pleased about this increased relevance in public discourse? Or does it risk overburdening the term and the educational field – especially when it comes to conveying and practicing democracy?

Monika Oberle: As a citizen, I can’t be pleased about the extent to which liberal democracy is currently under pressure – both from within and from outside. It’s true that calls for civic education are becoming louder these days. But civic education is not a fire brigade that can rescue a precarious democracy on its own, and certainly not on short notice. That would overload expectations. At the same time, civic education is highly relevant for a functioning and vibrant democracy. Intervention studies show, for example, that civic education measures can compensate for inequalities in political competence that arise from other socialization factors like family background. That is why it’s crucial to translate the kind of discourse you describe into concrete political action by sustainably equipping both formal and non-formal civic education with adequate resources and ensuring continuous scientific evaluation.

How would you summarize the findings of the Pilot Monitor? What’s the current state of civic education in Germany?

There are significant disparities in both the quantity and quality of civic education people in Germany receive. These vary not just by state – due to Germany’s federal education system – but also by social background. As such, aside from the Gymnasium, the other secondary school types in Germany offer significantly less political instruction taught by qualified teachers. In non-formal youth and adult civic education, which is based on voluntary participation, programs often reach those who are already politically interested, while people with lower educational attainment are less likely to be involved. We are still far from achieving equal access to civic education in Germany.

Politics and civics are often taught by teachers without a degree in political science. Does that constitute a basic problem? Don’t teachers from other disciplines bring valuable perspectives? And if you argue that politics can also be addressed in math or foreign language classes, doesn’t that mean the teacher doesn’t necessarily need to be a political scientist?

Teachers from other disciplines also need proper training to incorporate civic education into their lessons. Integrating politics and democracy education into teacher training – both at universities and in professional development – is still lacking in many places. That said, a German or math class can only supplement civic education; it cannot replace specialized political instruction. Political science instruction provides a space to explore politics in all its dimensions: polity (structures), politics (processes), and policy (content), as well as democracy as a system of governance. It systematically fosters students’ capacity for judgment and action in democratic decision-making. For this to be effective, the instructors must be academically and didactically qualified in political science. The share of civics instruction taught by non-specialists – ranging from 25% in Gymnasium college-preparatory schools to over 60% in Realschulen and Hauptschulen – is unacceptable.

A major point of controversy is how “neutral” teachers must be in the classroom. How would you define their role: as moderators, correctors, observers?

There is no requirement for political neutrality in civic education. State-sponsored civic education is explicitly values-based. It is anchored in the fundamental values of our liberal democracy: respect for human dignity, democracy, and the rule of law. Teachers do not have to hide their political views; in fact, there are strong arguments in favor of disclosing them – for reasons of authenticity, serving as a political role model, and avoiding covert indoctrination. However, the educational setting must always promote multiperspectivity, encourage students’ independent judgment, and avoid indoctrination. Navigating the balance between core democratic values and the principle of presenting controversies can be a tightrope walk at times. But even gray areas can be addressed transparently and in a cognitively stimulating way.

Educational institutions are supposed to be places where politics is not only taught but lived. What are the deficits and challenges in this regard?

In secondary school systems other than the German Gymnasium – where students are more likely to come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds – democratic practices and participation are implemented less frequently. Much depends not only on legal frameworks, but also on the individual school leadership and teaching staff. That’s why it’s so important to embed democracy education as a core mission in the training of school principals and to learn from best practices. External actors in civic education – working with student councils or other peer-to-peer formats – can also provide valuable impulses. Meaningful participation also requires real opportunities for decision-making. When voluntary engagement structurally leads nowhere, it can quickly result in frustration.

What are the specific challenges in the field of non-formal education? Where does civic education take place outside of school settings?

Non-formal civic education is extremely diverse in terms of both providers and formats. It takes place throughout life – including in youth education centers, adult education centers (Volkshochschulen), theaters, museums, workplaces, digital spaces, and other everyday settings as part of outreach education. Participation is mostly voluntary, which brings advantages (like motivation and openness) but also challenges (like the risk of preaching to the choir).

One challenge for monitoring non-formal education is the heterogeneity of available data and significant data gaps, which make comparisons across providers, regions, and time difficult. In the Pilot Monitor, we therefore not only compiled available data on key actors and public funding flows but also conducted a standardized cross-provider survey and collected representative public opinion data.

One of your other projects focuses on empowering civics teachers for democracy education and radicalization prevention – particularly on the topic of antisemitism as a cross-cutting narrative (PolRapLi-III). What insights have you gained, especially given increased tensions due to the war in the Middle East?

In these polarized times – when disinformation and conspiracy theories (especially on social media) are rampant and any discussion on wars and “crises” becomes highly emotional – civics teachers face major challenges in the classroom. Teaching needs to connect with students’ everyday lives while fostering factual orientation, perspective-taking, discourse skills, a grounding in democratic values, and the ability to tolerate ambiguity. Our new training program focuses on antisemitism as a cross-cutting narrative that fuels anti-democratic movements across the political spectrum. It will be piloted this summer, accompanied by systematic research and further development. Results from our recent online survey of civics teachers in Hesse and Lower Saxony underscore the urgent need for training in this area.

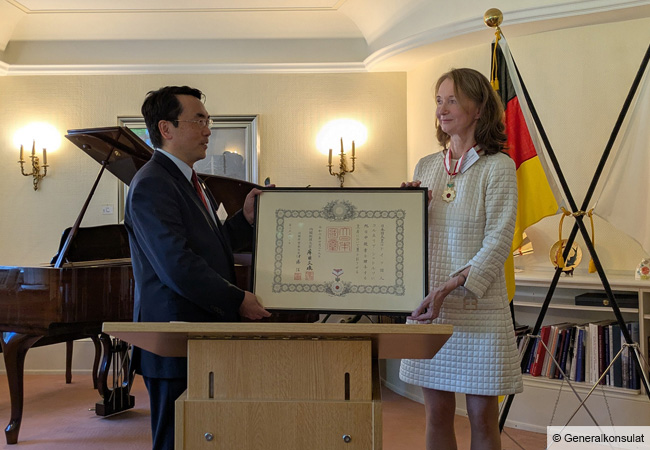

The project “Feasibility Study: Monitor Civic Education”, funded by the Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb), has been jointly led since 2021 by Prof. Dr. Hermann Josef Abs (University of Duisburg-Essen), Prof. Dr. Tim Engartner (University of Cologne), Prof. Dr. Reinhold Hedtke (University of Bielefeld), and Prof. Dr. Monika Oberle (Goethe University Frankfurt).

The Pilot Monitor for Civic Education is available for free download →