A research project on propositionalism

How do words and phrases combine to form meaningful sentences? And how can we analyze the contents of these sentences? Linguistics researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt aimed to demonstrate how the theory of propositionalism, which is not too widely known even among linguists, represents a suitable approach. A quite complex topic.

Before we turn to propositionalism itself, we must first answer – at least provisionally – several more fundamental questions: What are the meanings of linguistic expressions (like words or sentences)? How do hearers understand these expressions and their meanings? How are the meanings of complex expressions composed from the meanings of their constituents?

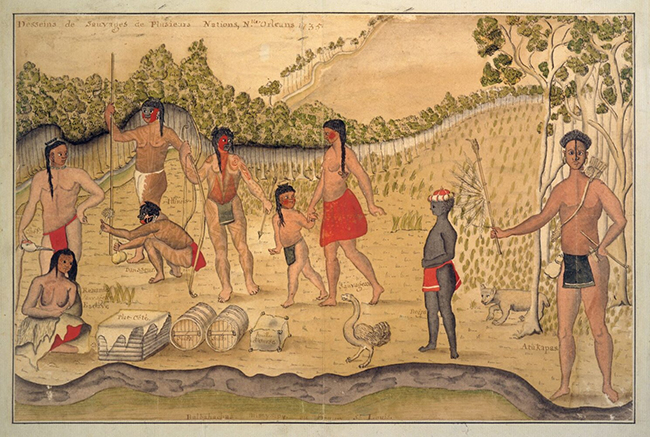

These and similar questions are explored in formal semantics, a branch of linguistics. The findings of this foundational research are relevant for computational linguistics, among other applications. In particular, formal semantics investigates the structural rules of languages that make it possible to construct specific meanings from words and sentences. “Propositionalism in Linguistic Semantics” – a Reinhart Koselleck Project at Goethe University Frankfurt funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) – aimed to shed light on how this acquisition of meaning works in the case of attitude reports (for example: “Heinz thinks that Merz is the President of the USA”). The central claim of propositionalism is that all attitude verbs (these include, for example, “think”, “want”, “imagine”) are related to sentence contents as meanings. But is that true?

Let us first look at words: Anyone who wants to read and understand a newspaper article – and benefit from doing so – should ideally know all of the words used in it. Only on this basis can a reader grasp the content of a text. But the meanings of individual words are not enough. In semantics, the path from word meanings towards the meanings of more complex units (phrases) and sentences and on to the contents of entire texts is referred to as “compositionality”.

How should we imagine this process of understanding? In compositional semantics, we imagine compositionality as an intertwining of the meanings of smaller parts. The meanings of individual words and parts of sentences are understood as their potential to combine with one another to form varying sentence contents – like pieces of a puzzle that, when joined together correctly, produce a coherent picture, or meaning. An analysis of the meaning of sentences such as (1) can serve as an example:

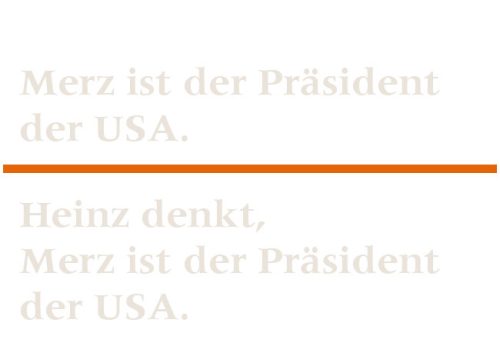

(1) Merz is the President of the USA.

In this context, the meaning of the auxiliary verb “is” can be imagined as a piece of a puzzle that, together with two matching pieces, form a complete sentence. “To be”, just like “to become” and “to remain”, belongs to a group of verbs called “copulas”. These do not transport any particular meaning by themselves. Instead, they serve first and foremost to connect other parts of the sentence. The meanings of “Merz” and “the President of the USA” are such matching puzzle pieces. Together with the verb “is”, they form the content of sentence (1).

In formal semantics, we use methods from mathematical logic to model linguistic meanings, treating them as functions – in this case, a function with two “arguments” (“inputs”) that interact with one another in the resulting content of the sentence, i.e. the value of the function (its “output”). Compositionality thus consists, in this case, in the application of a function, the meaning of the copula, to two arguments, the meanings of the nominal parts.

AUF DEN PUNKT GEBRACHT

- Die formale Semantik ist ein Teilbereich der Linguistik. Sie untersucht, wie sprachliche Ausdrücke miteinander kombiniert werden, um eine Bedeutung zu erzeugen. Sie nutzt logische und mathematische Modelle, um diese Prozesse zu analysieren und anzuwenden.

- Die Bedeutung von komplexen sprachlichen Ausdrücken entsteht durch das Zusammenspiel der Bedeutungen ihrer Bestandteile. Die Bedeutungen von Wörtern und Satzteilen verbinden sich zu einem Gesamtinhalt.

- In der modernen Semantik wird die Bedeutung eines Satzes als eine Proposition verstanden, die durch verschiedene mögliche Szenarien beschrieben wird, auf die der Satz zutrifft.

- Die These des Propositionalismus besagt, dass alle Einstellungsverben (z. B. »denken«, »wollen«) eine Beziehung zum Inhalt eines Satzes (Proposition) ausdrücken, der die Bedeutung des Satzes ausmacht.

- Das Koselleck-Projekt zeigt, dass der Propositionalismus auch auf viele komplexe Fälle angewendet werden kann. Eine präzise mathematische Analyse kann helfen, die Bedeutung in diesen Fällen zu analysieren.

Meaning composition and sentence contents

In semantics, the meanings of all linguistic expressions are analyzed as contributions to sentence meanings. But what exactly are sentence meanings, also known as sentence contents, or propositions? To answer this question, modern semantics can draw on groundwork from another discipline, formal logic, where – building on the formalization of mathematical theories – methods were developed as early as the beginning of the 20th century to analyze the contents of sentences (expressed in specific contexts). Here, the information content of a sentence is represented by the range of possible scenarios to which it applies. In our example, these scenarios are entirely fictional, since the sentence does not apply to any real situation: It is false (in contrast to, for instance, the sentence “Trump is the President of the USA”). But the fact that the sentence in our example is false does not necessarily make it impossible for some individuals to consider it true – perhaps due to substantial misinformation. If Heinz is someone misled in this way, one can accurately state that:

(2) Heinz thinks that Merz is the President of the USA.

The compositional analysis of sentence (2) proceeds in a similar way to that of sentence (1): The verb “think” has a meaning that combines with the meanings of the other two constituents to form the content of the sentence. However, for this verb meaning, the second gap differs from that in (1): here, a sentence content must be inserted, namely the content of sentence (1). This sentence content fills the second gap in the verb meaning, so that after filling the first gap with the meaning of the name “Heinz”, a new sentence content is created, namely that in (2).

Propositionalism and attitude reports

In semantics, sentences like (2), which describe an individual’s mental attitude towards a specific statement, are called “attitude reports”. They typically have the form “x Vs S”, where “x” refers to an individual (the attitudinal subject Heinz), “S” is a subordinate clause and “Vs” is a suitable verb. Using the technical term for sentence contents – “proposition” – attitudes such as (2) are often referred to as “propositional attitudes”.

Linguistic literature on attitude reports almost exclusively analyzes propositional attitude reports – that is, attitude reports in which a subordinate clause fills the second gap. This focus on propositional attitudes forms the basis for the central claim of propositionalism, according to which all linguistic material embedded in an attitude verb (“S” in the preceding paragraph) is sentential (i.e. contains a proposition). There are good reasons for this assumption. Most importantly, it facilitates a uniform analysis of all attitude contents. Since propositions stand in logical relations to other propositions (for instance, (3a) follows from (1)), propositional attitude contents are practically automatically equipped with a logical system of inference. This system predicts the validity of the inference from (2) to (3b).

(3a) The USA have a president.

(3b) Heinz thinks that the USA have a president.

Initial challenges for propositionalism

However, not all attitude reports exhibit a propositional structure like that in (2) and (3b), and it is precisely this observation that raises questions for our project. This applies, for example, to the report in (4), where the attitude verb “want” embeds an expression referring to an object (“a faster PC”). Since such linguistic expressions do not have propositions, but rather individuals or properties as their meanings, they seem to contradict the propositionalist claim.

(4) Oskar wants a faster PC.

Early proponents of propositionalism – including Willard Van Orman Quine (1956) – have developed a simple strategy to account for desire reports like (4): They break down the attitude verb (“want”) into a semantically equivalent combination of a propositional (!) attitude verb (here: “wish/want”) and an additional predicate (“have”). The latter then helps in the production of whole sentences, as in the strategy for forming (1). The propositional analysis of (4) is illustrated in (5) below.

(5) Oskar wants to have a faster PC. (or)

Oskar wishes that he had a faster PC.

Difficult challenges

But simply replacing “a faster PC” in (4) with another description, such as “a (cup of) coffee”, already causes problems for the strategies presented above: Oskar’s desire for a (cup of) coffee is presumably not satisfied by his possessing a cup of freshly brewed coffee – he wants to drink the coffee (not just to have it). Tricky cases like this one also pose distinct challenges for the Koselleck project funded by the DFG.

In addition to the coffee example presented above, these challenges include attitude reports like (6) and (7), for which it is either unclear how the verb should be decomposed, or in which there appears to be no suitable supplementary predicate, such as “have” or “drink” from the previous examples. It thus remains open, for example, whether “picture” in (6) is to be interpreted as “seem to see”, “pretend to see”, or “imagine how … sees”.

(6) Uli pictures a unicorn.

(7) Peter likes Anna.

Sentence (7) is even more problematic. It seems that there might not be any suitable predicate at all that could combine with “Anna” to form a sentence. This is the case if Peter likes Anna for who she is, where this is not tied to any specific property of Anna (Grzankowski, 2016).

By carefully analyzing these and other examples, the Koselleck project team was able to demonstrate that the set of cases that allow for a propositionalist analysis is far larger than previously assumed – if one uses sophisticated methodological approaches from mathematical logic. Indeed, fundamental research in logical semantics has corroborated the long-standing suspicion in formal semantics that all semantic analyses can be reformulated in order to meet the requirements of propositionalism. However, the substitute phrases often risk to not only bring with them the above-mentioned advantages of propositionalism, but also to unnecessarily complicate meaning composition.

Literatur

Grzankowski, Alex (2016). Limits of propositionalism, Inquiry 59(7-8): 819-838.

Liefke, Kristina (2024). Intensionality and propositionalism, Annual Review of Linguistics 10: 4.1-4.21.

Quine, Willard Van Orman (1956). Quantifiers and propositional attitudes,

The Journal of Philosophy 53(5): 177-187.

Zimmermann, Thomas Ede (2014). Einführung in die Semantik, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

– (2025): Propositions and Attitudes (pending publication in Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft).

The author

Thomas Ede Zimmermann, (born in Hannover in 1954) became acquainted with modern grammar theory while he was still at school. His enthusiasm for the formal modeling of linguistic structures first led him to study at

the University of Konstanz, which was the stronghold of theoretical linguistics back then. After completing his Master’s degree, he worked as a researcher in CRC 99 “Linguistics” and earned his doctoral degree with what must be the shortest dissertation in the field (13 printed pages). Following further career stages at the newly founded institutes of computational linguistics in Tübingen and Stuttgart, he accepted a call to Goethe University Frankfurt in 1999, where he worked as a Professor of Formal Semantics until his retirement in the

fall of 2020. He was the spokesperson for a research group on relative clauses and led the Koselleck project on propositionalism (from 2018 onwards). As the author of two textbooks, as a regular lecturer at international summer schools, and in the context of several visiting professorships at US universities, he teaches the fundamentals of his field to the next generation of academics.

t.e.zimmermann@lingua.uni-frankfurt.de

Die Autorin

Kristina Liefke, (born in Neumünster in 1983) knew from her first linguistics seminar that semantics would captivate her forever. In order to avoid having to choose between linguistics and philosophy, she went to the “semantic Netherlands” to undertake her doctoral degree (which she earned at Tilburg University in 2014). After postdoctoral positions at the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy and Goethe University Frankfurt (in the Koselleck project mentioned above), she was appointed Junior Professor at Ruhr University Bochum in 2020. A colleague recently aptly described her professorship, “Philosophy of Information and Communication”, as “Philosophical Semantics and Pragmatics”. She is working on propositionalism and models of communication, as well as the semantics of memory representations.

kristina.liefke@ruhr-uni-bochum.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding