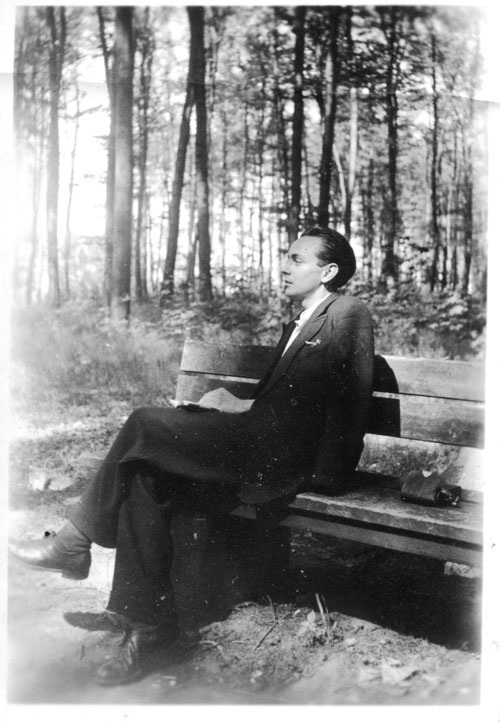

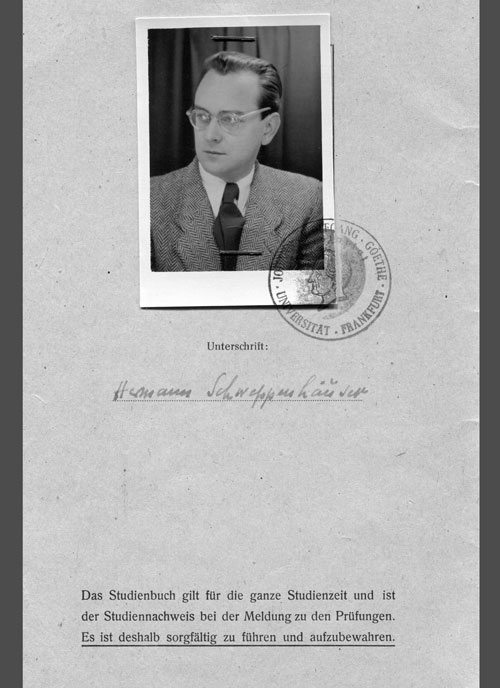

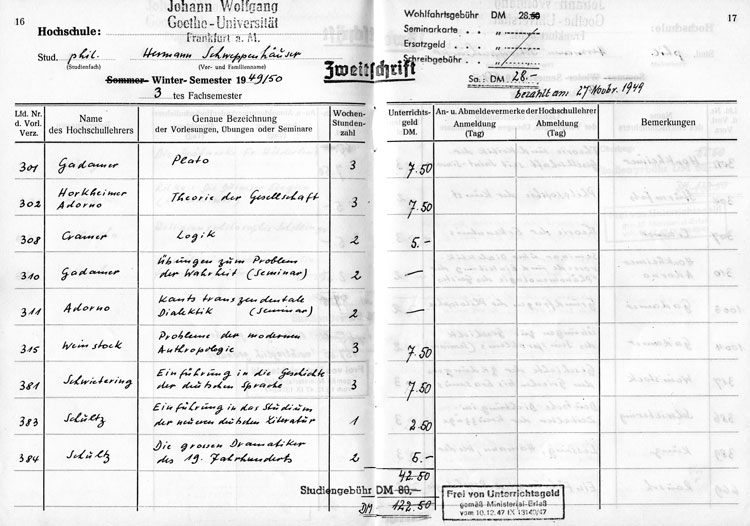

The Archive Centre of the Johann Christian Senckenberg University Library has been able to expand its collection of material on critical theory thanks to the bequest of philosopher Hermann Schweppenhäuser (1928-2015). Schweppenhäuser earned his doctorate in 1956 at the Institute for Social Research, which by that time had reopened. He was Theodor W. Adorno’s assistant up until 1961 and one of the most influential philosophers of the Frankfurt School. His bequest comprises about 75,000 pages and extensive unpublished archive material, which is accessible for research purposes at the Archive Centre.

Dr. Mathias Jehn, director of the Archive Centre, is very pleased: “This expands our collection on critical theory and the Frankfurt School tremendously. Our stock already includes, amongst others, the bequests of Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse and Ludwig von Friedeburg as well as lifetime contributions from Jürgen Habermas and Oskar Negt.” The Institute for Social Research is also home to the Adorno archive and valuable historic stock from the 1950s and 1960s. Some of the Schweppenhäuser bequest has yet to be processed: “It’s so vast that this is going to take at least another twelve months”, says Jehn. But the bequest, which comprises extensive correspondence with international experts from the field of philosophy, partly unpublished scientific manuscripts as well as a few private documents, is now entirely in Frankfurt and was entrusted to the library by Gerhard Schweppenhäuser, the philosopher’s son.

In 1961, Hermann Schweppenhäuser, who was born in Frankfurt, moved to Lüneburg where he had been called to the newly established chair of philosophy at the College of Education. What was originally supposed to be an intermezzo became a lifetime post accompanied by an honorary professorship at Goethe University Frankfurt. Adorno evidently had other ideas too: in a card dated 14 October 1960 from Graz, which is also part of the bequest, he congratulated Schweppenhäuser “most sincerely” on his appointment in Lüneburg and added: “I hope that you will accept the post, which will certainly allow you to gain considerable experience, and this hope goes hand in hand with the hope that you will complete your post-doctoral degreequicklyand stay with us!”

Yet the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, which never was or is seen by most of the researchers involved as a closed circle with a uniform theory, developed in another direction and so Schweppenhäuser was not called to Goethe University Frankfurt. Habermas, who became Horkheimer’s successor in Frankfurt in 1964, retaliated several times in public against “being categorized uninterruptedly as a critical theorist”, although he had worshipped Adorno, as his biographer Stefan Müller-Doohm notes. Habermas developed his own independent idea of a societal communication theory “which regards itself not as transformation but entirely as an alternative to the critical theory of society”, says Müller-Doohm in an article in the FAZ newspaper (2016).

Whilst Habermas indeed shared Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s criticism of the one-sided technical and economic rationalization of modern culture and society, he chose a different perspective and focused his diagnosis on a “problematic primacy of economics over democratically legitimized politics, with which societies influence themselves”, says Müller-Doohm.

In the obituary he wrote for the weekly “jungle world” newspaper (2015), Roger Behrens is critical of the fact that Goethe University Frankfurt did not give Schweppenhäuser a chance: “Schweppenhäuser’s philosophy is the attempt to justify critical theory […] without falling into the trap and postulating on normativity, as did Jürgen Habermas and the academics who followed him […]. In contrast, Hermann Schweppenhäuser – a year older than Habermas incidentally – vigorously pursued the postulate of critical theory, in line with Horkheimer and Adorno, in line with Karl Marx and in line with Kant – as radical enlightenment [and] critique of power.”

Although not all documents have yet been viewed, the bequest makes it clear that Schweppenhäuser significantly shaped the discourse on Adorno and Benjamin through numerous essays, which enjoyed international acclaim and were partly translated. Schweppenhäuser formulated a version of critical theory “which is closer to the prime intention of Horkheimer and Adorno than the Frankfurt School with its communication theory as reformed by Habermas and his successors”, says his son Gerhard Schweppenhäuser. His lectures, for example on the “Characteristics of Adornoesque Thinking” or the “Dialectics of Enlightenment” made “authentic study” of critical theory possible in both Lüneburg as well as Frankfurt.

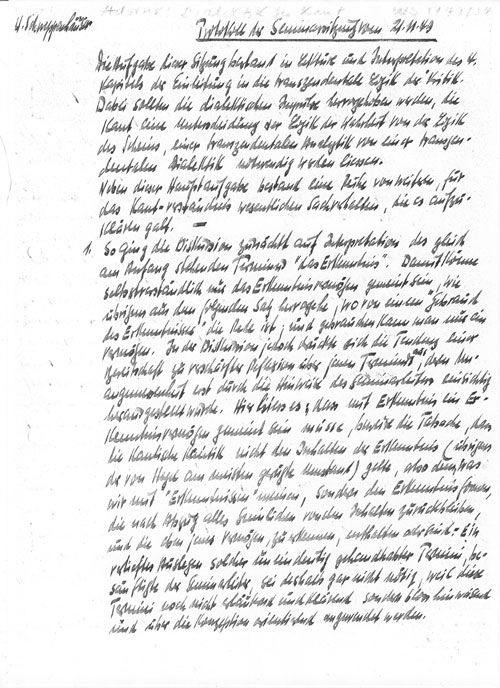

In his philosophical writings, Schweppenhäuser dealt with the self-reflection of dialectical thinking, the philosophy of language, aesthetics and critique of culture and current times as well as with the relationship between philosophy and theology. In the 1970s, he published the Collected Works of Walter Benjamin (Suhrkamp Verlag) together with Rolf Tiedemann. The bequest, numbered as “Na 77 Nachlass Hermann Schweppenhäuser”, includes numerous unpublished texts of many different kinds: from subject-specific deliberations to elegantly formulated aphorisms and fragments to literary productions in the fields of poetry and short prose. Attempts at playwriting from his student days are also waiting in the archive to be discovered. A first small selection of aphorisms from the Schweppenhäuser bequest appeared in the commemorative volume “Image and Idea” (Bild und Gedanke) published in 2016.

The extensive correspondence, which is also part of the bequest, shows just how close the philosopher’s dialogue with international academics was. These included, amongst others, Giorgio Agamben (Italy), Siegfried Kracauer (USA), Herbert Marcuse (USA), Gerard Raulet (France), Gershom Scholem (Israel), Gary Smith (USA), Ulrich Sonnemann (Germany) and Moshe Zuckermann (Israel).

Source: Press Release 06/02/17