Questions for Dr. Judith Müller, Research Associate at the Buber-Rosenzweig Institute and co-organizer of the conference “European Hebrew Text Cultures: Deciphering Entanglements through Close and Distant Readings,” which took place at Goethe University Frankfurt in late May.

UniReport: Many people know that Hebrew is the traditional language of Judaism. But it’s usually associated either with religious texts or – in its modern form – with present-day Israel. However, there’s also a European history of modern Hebrew literature. When did this tradition begin, and who was writing in Hebrew?

Judith Müller: Indeed, the history of modern Hebrew literature begins in Europe. It laid the foundation for the Hebrew literature that was later written – and continues to be written – in Israel, but it also connects back to the religious text tradition you first mentioned. In the 19th century, Hebrew began to spread as a didactic language of religious renewal, especially through Haskalah, an intellectual movement often referred to – somewhat simplistically – as the Jewish Enlightenment, in that it also critically engaged with traditional religious norms. Through Haskalah, there was a fluid transition from educational and manifesto-style texts to journals, verse epics based on religious themes, and eventually the first Hebrew novel by Abraham Mapu, published in the second half of the 19th century. As Hebrew became more widespread, both the language and the literature underwent a process of secularization, leading to modern European-style poems and novels whose themes and concerns were no different from those written in German, French, or English. For a long time, however, access to the language was available only through religious institutions – i.e. Talmud schools. As a result, most Hebrew writers were men, although not exclusively so. Important female authors from the first half of the 20th century include Dvora Baron and Lea Goldberg.

What motivated writers to write in Hebrew and not (only) in their native languages? Were their efforts tied to a sense of Jewish nationhood?

Yes, some writers were mainly motivated by the desire to contribute to a national Hebrew literature – even though the readership was initially very small. As more people began to write in Hebrew, the literature became more diverse, and not all were writing from a Zionist perspective. It’s important to keep in mind that many Jewish writers – especially those originally from Eastern Europe, who accounted for most Hebrew writers at the time – were not simply bilingual but often spoke three or four languages. Their mother tongue was usually Yiddish; Hebrew began as a religious language but increasingly opened up new expressive possibilities. In addition, there was at least one national language – such as Russian. Some writers didn’t feel comfortable enough with this language to write creatively in it or didn’t want to limit themselves to a Russian-speaking audience. Yiddish, on the other hand, carried many negative connotations and was seen by some as a “low” language, so Hebrew emerged as the classical, elevated alternative.

Your June conference took a cross-country, interdisciplinary, and diachronic approach to the phenomenon of European Hebrew literature. What were your key takeaways?

The most important insight was that Hebrew literature, across all its entanglements, not only spans multiple epochs and geographic locations, but that it has always been in dialogue with various cultures and traditions. From this, we can draw two further conclusions: First, tradition plays a central role in the emergence and establishment of a new literature. Second, in the case of Hebrew literature, the renewal of the language itself supported this process. During the conference, it became clear that engaging with tradition refers not only to Jewish religious traditions but also to Christian traditions – as those of the majority society – as well as classical Greek mythology as part of a general humanistic education. Conference participants also highlighted that the renewal of the language involved critical inquiry as well as the invention of new words – both developments that predate Zionism. The influence of multiple languages on Hebrew and its speakers – especially Yiddish – also needs to be considered. In this sense, the conference made a valuable contribution by bringing together diverse perspectives on the texts and examples presented at Goethe University.

Why was it important that the conference be held in Frankfurt?

Unlike Berlin or Vienna, Frankfurt may not be the first city that comes to mind in the German-speaking world when one thinks of the history of Hebrew literature in Europe. But Goethe University offers exciting research opportunities in this field. Thanks to the Specialized Information Service for Jewish Studies, the university provides access to scholarly literature that is not available in every German-speaking academic library. Moreover, Goethe University’s Judaica collection documents the centuries-old connection between Hebrew and German-speaking Jewry – far beyond the Enlightenment and emancipation. This was one reason we visited the collection with the conference participants and examined highlights like early Frankfurt-area Haggadahs and Talmud editions, Hebrew journals from the Haskalah period, and even modern Hebrew literary works translated and printed in Frankfurt.

In addition, we were able to bring together the Department of Jewish Studies and the Buber-Rosenzweig Institute – part of the Faculty of Protestant Theology – which strengthened internal university collaboration, even though that wasn’t our main goal at all. Dr. Orel Sharp, who spent two years as a Minerva Fellow at the Department of Jewish Studies and whom I know from our joint doctoral time in Be’er Sheva, and I wanted to make use of the rare opportunity of having two researchers with a focus on modern Hebrew literature at the same university in Europe. Unfortunately, that is not a common occurrence.

And beyond the university? Frankfurt and the surrounding region have a strong Jewish history. Were there any connections to Hebrew-language authors?

Yes! Interestingly, though, for the pre-war period, we know more about Hebrew writers in Bad Homburg than in Frankfurt. For example, future Nobel laureate Shmuel Yosef Agnon lived for a time in the spa town and worked closely with Martin Buber during that period. Hayim Nahman Bialik and publisher Shoshana Persitz also spent time there.

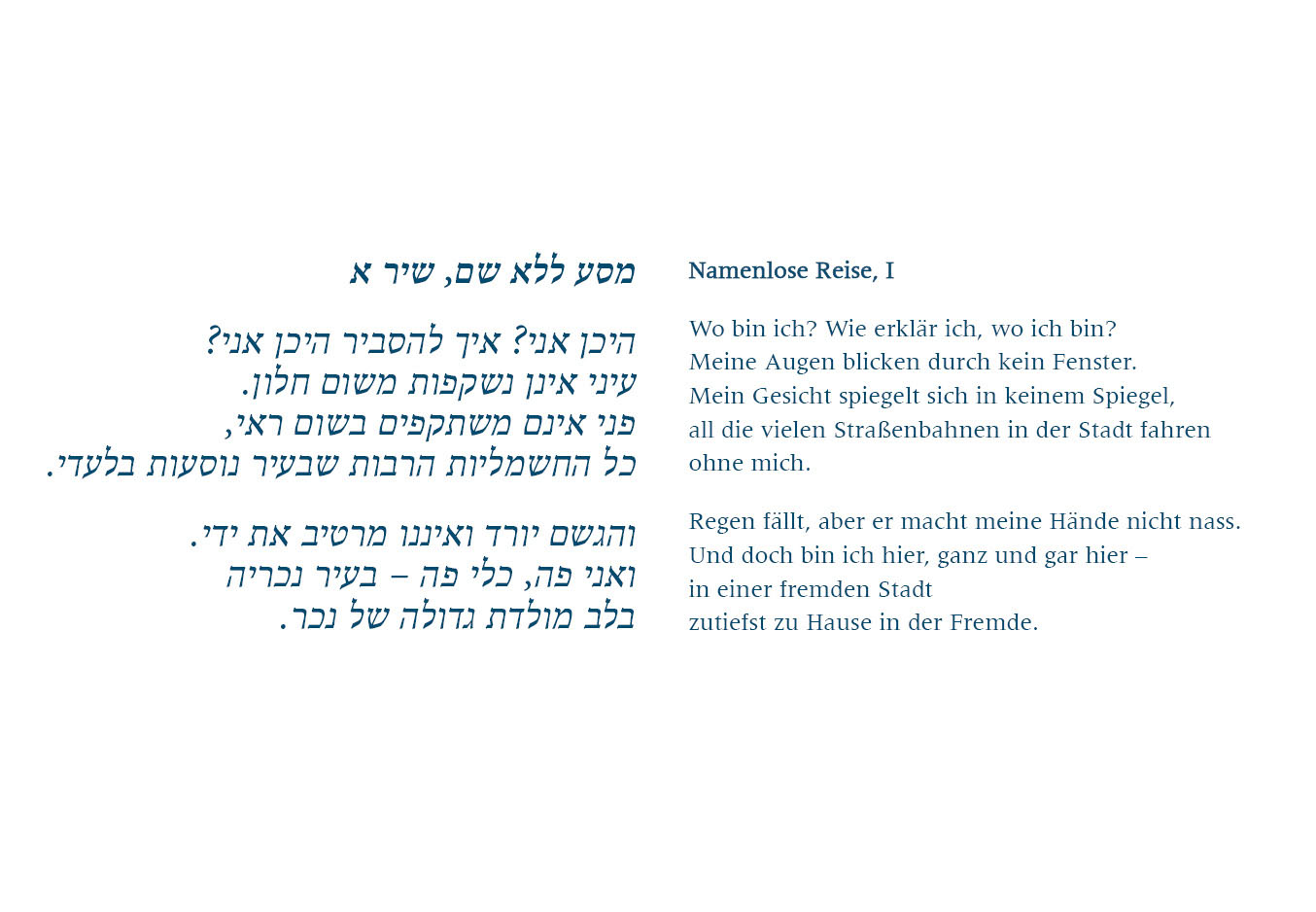

Which Hebrew-language European author should no one miss? And do you have a personal favorite or hidden gem?

Because so little of prewar European Hebrew literature has been translated, there’s a lot that readers are missing out on. One hidden gem – and a personal recommendation – is Lea Goldberg. Her novel “Verluste” [Losses] was published in 2016 in a German translation by Gundula Schiffer. Some of her poetry has also appeared in German translation. In addition, Yfaat Weiss’ translated monograph traces Goldberg’s academic path – especially at the University of Bonn.

Questions: Louise Zbiranski, Science Communication Officer for the research network Dynamics of the Religious and Coordinator of the platform “Schnittstelle Religion”.