200 years of the Physikalischer Verein: Birthplace of the natural sciences in Frankfurt

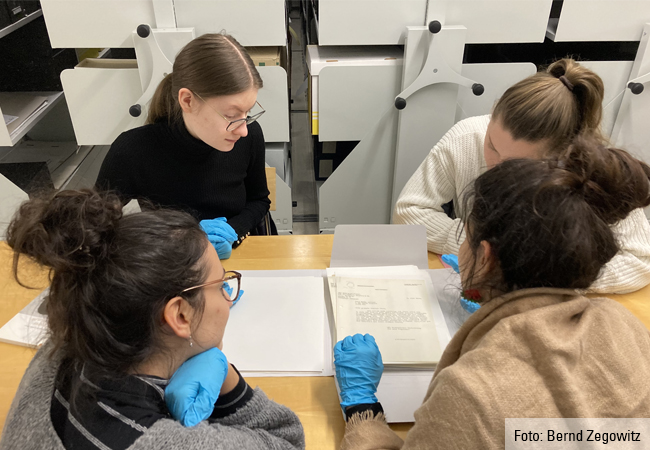

On a trip to his native Frankfurt in 1815/16, Goethe lamented the lack of an educational institution devoted to the natural sciences. Less than a decade later, on October 24, 1824, the Physikalischer Verein [Physics Association] was founded. The driving force behind this was Christian Ernst Neef, a doctor at Frankfurt’s Bürgerhospital, who, however, unlike the prince of poets, did not think of it as a noble pastime. Rather, Neef pointed out that the natural sciences and engineering had helped countries such as England and France to power and prosperity. As a center of commerce, Frankfurt could not afford to ignore this.

Ten gentlemen convened for the association’s first meeting, held in the rear building of the Hotel Reichskrone in Schäfergasse. Among them were doctors, teachers, a pharmacist, a notary and the “citizen and merchant” Johann Valentin Albert, who placed his collection of physico-technical apparatus at the association’s disposal. The Physikalischer Verein’s purpose was anchored in its statutes: “[…] to teach each other, with the aim of spreading knowledge of physics and chemistry more generally, and to foster and enrich these sciences themselves as much as possible […]”.

Assessors for the city: What caused the fire and who adulterated the beer?

The association was founded at a time of growing enthusiasm for popular science lectures and magazines as well as private collections. Albert’s collection contained disc calculators, hydraulic machines, a Coulomb torsion balance, photometers, polarization devices, electrostatic generators, quadrants, a reflecting telescope (an invention of astronomer Wilhelm Herschel) and a model of the planets, but also curiosities such as a Chinese puppet theater. Members of the Physikalischer Verein were allowed to use the instruments for an annual fee of six guilders. A stove, an oven and chemical appliances were available for chemical work. Users had to pay for reagents themselves. Members were allowed to bring their wives, as well as children aged 15 and over, to the lectures.

Beyond scientific research and education, the Physikalischer Verein also compiled technical expertises for the city. Its annual reports document numerous, sometimes abstruse inquiries, for example about the spontaneous combustion of mutton trotters, which were suspected of being the cause of a fire. Its members were also asked to comment on disputes in the neighborhood following complaints about a soap boiler and a malt grist. They inspected fire hazards in factories, steam engines, and a new process for cleaning privies, among others.

Testing the purity of beer is likely to have been one of the more pleasant tasks, which could help explain why the association appointed a five-person commission for this.

Introducing order to the cacophony of clock towers

In 1837, the members of the Physikalischer Verein offered to synchronize Frankfurt’s clock towers. In 1838, a measuring station was installed on the tower of St. Paul’s Church. It had a chronometer (a particularly precise clock), a theodolite (a device for measuring angles) and a bell. This enabled the association’s clock committee to determine the Sun’s highest position at midday. The bell began to strike exactly 22 seconds before 12. One stroke every two seconds, so that its last stroke sounded at 12 noon. This was the signal for the bells of Frankfurt Cathedral and St. Catherine’s Church to strike noon. And for Frankfurt’s wealthy citizens to synchronize their watches.

From the very beginning, the association’s Meteorological Department published weather data in two newspapers, the “Oberpostamtszeitung” and the “Zeitung der Freien Stadt Frankfurt”. It was not long before laypeople also started helping. The Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg allowed the association to erect a hut on Großer Feldberg in the Taunus mountain range. The plan was for it to go into operation on January 15, 1827, to mark the occasion of a European campaign day for the 24-hour collection of weather data. The scientists set off on a heroic expedition in a snowstorm and only gave up when a formidable gust of wind tore off part of the roof.

Crowd pullers: Technical exhibitions and air shows

From 1869 onwards, the Physikalischer Verein set up weather stations in the city so that interested citizens could read the temperature, air pressure and humidity for themselves. In 1907, it even purchased a balloon for weather observations. When the International Aeronautical Exhibition (ILA) took place in Frankfurt in 1909 with the support of the Physikalischer Verein, the association introduced an aeronautical meteorological service for the first time. The air show on the new exhibition grounds was a great success and attracted more visitors than the International Motor Show in later years. Count Zeppelin came to Frankfurt with his airship, and the daredevil pioneers of European aviation competed against each other.

The ILA’s success was based not least on the International Electrotechnical Exhibition in Frankfurt, which had taken place 18 years previously, in 1891. Its organizing committee included numerous members of the Physikalischer Verein, most of whom also belonged to the Elektrotechnische Gesellschaft. Among them was Leopold Sonnemann, founder and publisher of the Frankfurter Zeitung newspaper. Inspired by the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris (for which the Eiffel Tower was built), Sonnemann had a very practical reason for proposing the technical exhibition in Frankfurt: For three years, the municipal authorities had unsuccessfully debated the question of whether alternating or direct current should be used for the city’s incipient electrification, especially for street lighting and trolleybuses.

Guncotton, matches and a telephone that failed to impress

In 1835, the Physikalischer Verein hired chemist Rudolf Christian Böttger, who conducted his own research and held lectures. During his 50 years of service, he invented several things, including guncotton, matches and a metallurgical process. It was also during this time that Johann Philipp Reis presented his telephone, which, however, failed to impress the association’s members.

A further milestone was the construction in 1887 of a larger, modern building at Stiftstraße 32, made possible by donations by Frankfurt citizens. Its lecture hall could hold 200 people, and over the next few years, the building accommodated more and more specialist departments. From 1889 onwards, the Electrotechnical College trained young people there.

X-rays in the hospital

The members of the Physikalischer Verein responded astonishingly quickly to the latest scientific discoveries, such as X-rays in November 1895. When physician Dr. Walter König, head of the Physics Department, received Röntgen’s offprint at the beginning of January 1896, he immediately asked the author for permission to inspect the procedure on site. On January 29, König took his own X-ray of an injured boy, which showed that the child had broken a metacarpal bone. The first lecture for an invited audience took place on February 9, followed by demonstrations for schoolchildren three days later.

The Physikalischer Verein opened an X-ray laboratory to examine patients sent by Frankfurt doctors and the neighboring Bürgerhospital. Amid high demand, the Dr. Senckenberg Foundation made another room available in September 1896. In 1906, the two institutions parted ways when they each moved into new premises. From then on Walter König’s successor, Carl Déguisne, concentrated his research on the physics of X-rays.

From the foundation of the university until today

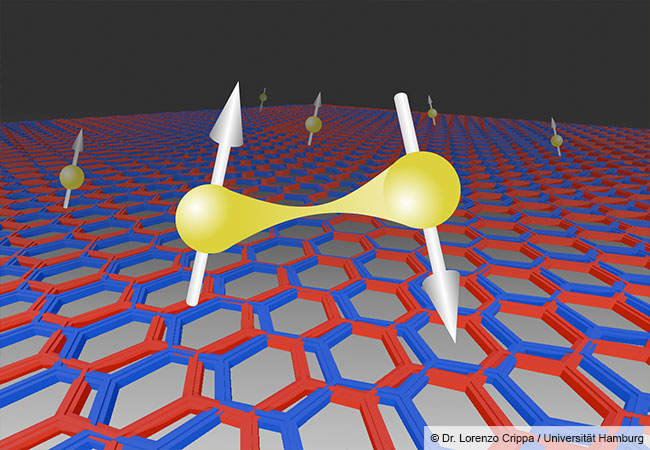

In 1914, the association contributed its institutes (physics, chemistry, astronomy, electrical engineering, meteorology and geophysics as well as physical chemistry and metallurgy), together with its laboratories, lecture halls, the observatory and the meteorological measuring station on the Feldberg mountain, to the newly founded university. Richard Wachsmuth, who alongside Franz Adickes, Lord Mayor, and industrialist Franz Merton had campaigned for the university’s establishment, became its first rector. Despite all the post-war hardships, the point of departure for the new university’s faculty of natural sciences was comparatively favorable. Members of the Physikalischer Verein donated money for equipment. In 1922, Otto Stern and Walter Gerlach conducted one of the first experiments, which corroborated the predictions of quantum theory (directional quantization in the magnetic field).

To this day, the Physikalischer Verein remains committed to popular science, and over the course of its history has inspired many to pursue a career in the natural sciences – including Karl Schwarzschild, the father of black holes, and Otto Hahn, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944 for the discovery of nuclear fission. Today, the association has over 2,200 members and concentrates above all on astronomy. It has three observatories: one on the roof of its building, which is open to the public every Friday evening, the observatory on the Kleiner Feldberg mountain, and a remote-controlled telescope in Spain with which the young members of the AstroClub are working.

“Astronomy is the best vehicle for conveying scientific understanding,” says astrophysicist Dr. Markus Röllig, who has served as Physikalischer Verein’s scientific director since 2023 and is reviving the old tradition of research. In times of ChatGPT and fake news, Röllig – who also teaches at Goethe University Frankfurt – believes the association’s main educational mission is to help people classify and correlate knowledge discerningly. “It’s important to know which questions to ask,” he explains. “That is the heart of science.”

Anne Hardy

HIGHLIGHTS IN THE ANNIVERSARY YEAR

Commemorative brochure:

Physikalischer Verein (eds.)

Stillt Wissensdurst: 200 Jahre Physikalischer Verein

[Satisfying the Thirst for Science: 200 Years of the Physikalischer Verein]

Frankfurt Academic Press 2024, 200 pages, €28

Official ceremony: October 24, 2024, Imperial Hall, Römer.

Lecture program and events:

https://www.physikalischer-verein.de/aktuelles/jubilaeum-200-jahre.html