Political order under conditions of armed conflict

by Hanna Pfeifer

Image: Champ008/Shutterstock

Civil war and chaos – these two terms seem closely related, the latter often appearing as an almost inevitable result of the former. But rebels and other actors involved in armed conflict also create order – and they sometimes do so by adopting institutions, personnel and practices from the pre-war context.

When we think of insurgencies or fully-fledged civil wars, images of violence and disorder, even of chaos, come to mind. Standard definitions in political science conceptualize intra-state conflicts as at least one rebel group fighting against the government. Civil wars, then, describe a situation in which one or multiple armed non-state actors oppose the existing political order – an order which, at least in theory, is defined and maintained by a state. For upon closer inspection, some pre-conflict orders are not simply state orders; the state may not appear in the same shape and make use of the same means in different places; and it may be very present in one location while being virtually non-existent in another.

The importance of non-state actors in West Asia and North Africa

Research on West Asia (often called the “Middle East”) and North Africa that emerges from area studies and political science has long emphasized the role of non-state actors in establishing and maintaining political order. On the one hand, even in peacetime these actors often step in where the state is negligent or does not fulfill its functions. A case in point are the charitable activities of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. On the other hand, some groups are closely intertwined with state structures – so much so that the distinction between “state” and “non-state” is no longer expedient (Pfeifer and Schwab, 2023). Lebanese Hezbollah, for example, is considered a militia or, according to the classification of various Western states, a “terrorist group”. At the same time, it also acts as a charitable organization that runs hospitals and schools. Finally, as it holds de facto territorial control in parts of Southern and Eastern Lebanon, it is sometimes referred to as a “state within a state”. However, given that Hezbollah also plays an important part in the “actual” state – as a party in the Lebanese government, with members in parliament and ministers in cabinet –, this description seems puzzling (Pfeifer, 2021).

Even without an ongoing civil war, then, it is not always easy to determine what makes up for the prevailing political order. However, when an armed conflict breaks out and authority is contested through violent means, orders can multiply. They stand as simultaneous offers of order, which may compete with each other but sometimes also overlap temporally or spatially. Such situations arise, for example, when a rebel group or another armed non-state actor manages to take control of a territory and hold it for a certain period of time. In most cases, civilians (and sometimes remaining employees of state institutions) live in these areas, and the rebels now face the question: What to do with them?

Rebel groups create new systems of order

For most armed groups, fighting remains the “main business” – be it against central government, other rebel groups, in some cases international forces or occupation troops. Some, however, choose to organize civilian life in the areas they control and start providing public goods and services (Kasfir, 2015). The physical integrity of the civilian population is a priority for such governing rebels. Apart from defending the territory, this includes setting up local police forces that see to “internal” security. Rebels often create mechanisms for conflict resolution, too, especially in the form of courts (Schwab and Massoud, 2022). To finance their activities, armed groups also introduce tax systems. Some rebels end up establishing differentiated institutional structures, which allow them to offer increasingly complex goods and services. In research, these arrangements are conceptualized as variations of “rebel governance”. They may intervene more or less deeply in the lives of the civilian population (Arjona, 2016). But why do rebel groups invest their already scarce resources in such endeavors at all?

For some groups, “managing” the civilian population by means other than coercion is simply cheaper. Violence against civilians may lead to costly uprisings against the ruling rebels, obliging them in the worst case to fight against both their actual opponents in the war and the local population. But even beyond such scenarios, exercising control and enforcing sanctions is relatively expensive. Finding other means to make the civilian population comply or even cooperate, at best voluntarily, can be the better option. Ruling groups may achieve this by providing goods and services or by enabling civil participation and involvement in governance. In this way, rebels can actually gain input or output legitimacy. In some cases, civilians find that their living conditions improve in certain respects, at least for some time (Revkin, 2021). This may be true for the broader population or for certain groups that the rebels consciously favor over others and that benefit from the new system. Rebels may discriminate that way based on religious or ethnic affiliation or other characteristics.

“ISIS” and its ambitious political order

Some armed actors also strive to establish a veritable “proto-order”, anticipating and testing the political order envisaged for the time after the revolution (Stewart, 2017). At the local or sometimes regional level, or in different localities simultaneously, a new community is constituted, institutions are redesigned or created from scratch, new decision-making processes are introduced, existing ones are adjusted. Rebels often symbolically mark that a new order is now in place (for example by hoisting a new flag). This order needs to be performed in different arenas (through the presence of security forces in public, through speeches in the media, through new procedures in institutions, etc.) and enacted in everyday life. The aim is to demonstrate that an alternative political order has been established – and that it is equal if not superior to the one offered previously or simultaneously by the state (Aarseth, 2021).

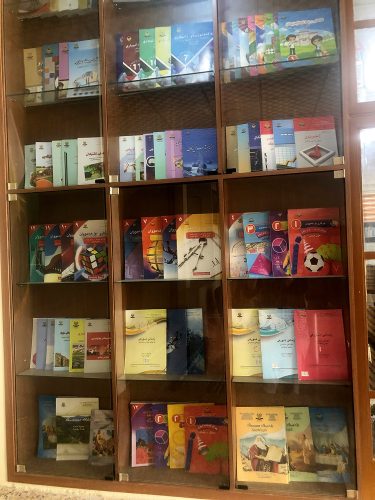

The “ISIS” organization, which refers to itself as the “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria”, is an example of an armed group with an ambitious political order project. At the height of its power in 2014, “ISIS” held territory in Syria and Iraq equal to the size of the United Kingdom. The group made Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, its “capital”. There, it set up various ministries (or government offices, dawawin), including a Ministry of Education headed by the German Reda Seyam (nom de guerre: Dhu al-Qarnayn). Between 2014 and 2017, this ministry carried out comprehensive reforms to the school system: It shortened the duration of regular schooling, altered curricula and the canon of academic subjects, and commissioned new textbooks. It retrained teachers, adapted educational content to its ideology and sought to establish itself as an authority in the field of knowledge, its production and dissemination – and thereby attempted to gain the trust of the population.

IN A NUTSHELL

• Rebellion and civil war are often equated with chaos. But rebels also create order.

• In West Asia (the so-called “Middle East”) and North Africa, the boundaries between state and non-state order are often blurred. Lebanese Hezbollah, for instance, is labeled a terrorist group, but it also runs schools and hospitals and is part of the Lebanese government.

• Under certain circumstances, rebels create new systems of order with police and courts, schools and tax authorities. This investment can be worthwhile for rebel groups, as it helps them gain civilian support.

• “ISIS”, which refers to itself as the “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria”, had a particularly ambitious vision for a political order. It set up ministries and implemented school reforms.

In my current research, I am dealing with this educational system. I analyze how “ISIS” went about redesigning schools, but also what practical problems the group encountered and how it sought to solve them. Contextualizing this “ISIS” project in Iraqi history (how did education work before “ISIS”?) is just as indispensable for this project as analyzing competing educational systems that existed elsewhere in Iraq at the same time (who competed with “ISIS” in the education sector?). After all, rebel rule never takes place in a vacuum but must position itself toward what existed before and keeps existing simultaneously: Rebels can opt

to simply reject existing forms of order, or reform, adapt or continue them. “ISIS”, for instance, could not simply present rows of new teachers and ministerial staff. Rather, it had to take over personnel, structures and buildings, and, with what were considered necessary “quick fixes”, at least provisionally, also old teaching materials. This shows that political orders – whether the attempt at a revolution is eventually successful or not – exhibit a remarkable degree of continuity beyond what at first appears as a rupture, often for purely practical reasons. Those who want to introduce a new order have to ask themselves: How can they convincingly demonstrate – despite limited resources and time pressure, and while facing performance expectations – that a revolution has indeed taken place?

To study this problem, I worked together with Abdulsatar Sultan from the Catholic University in Erbil and collected extensive data during field research in Iraq, from interviews with teachers and former students, observations in ministries and schools, textbooks, curricula and government documents. We were also able to draw on data that I had previously compiled with Houssein Al Malla from the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg. One of my first insights is that the aforementioned problem exists regardless of whether the concerned actor is a government in a new political system, an intervening third state or a rebel group. In the case of the education sector in Iraq, it appears that the American occupying force, the Kurdistan Regional Government and “ISIS” proceeded in similar sequences to implement changes in schools and universities. This included, for example, the systematic replacement and eradication of previously existing stocks of knowledge, the ad hoc use of temporary substitutes from other educational systems (textbooks, model curricula, and so on), transnational learning and the development of their own materials and bodies of knowledge, as well as adopting forms of knowledge production and dissemination, and taking over institutions and personnel from the “system of the past”.

As part of the ConTrust research initiative, several dozen researchers from Goethe University Frankfurt and the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) are investigating how trust can develop in conflict, even under conditions of extreme uncertainty such as mass protests, revolutions or civil wars (Pfeifer and Weipert-Fenner, 2022). In this context, I investigate how different actors tried to gain the trust of the Iraqi population – more generally in the respective political system and particularly in newly created epistemic authorities. When orders overlap and supersede each other, whole bodies of knowledge are systematically devalued, and truth becomes a subject of contestation. Whom, then, can civilians trust under conditions of changing rule? This is an urgent question for the case of Iraq, but it is also relevant in other contexts such as in Germany. Here, too, we are still dealing with the consequences of two competing orders that had existed in one society for several decades – and one ending abruptly with German reunification. These days, we are experiencing declining trust in political institutions, forms of knowledge-production and epistemic authorities, and these crises have to do not least with ruptures in the past and those yet to be expected. Comparative and interdisciplinary studies with neighboring disciplines in the profile area “Orders and Transformations” at Goethe University Frankfurt are therefore a worthwhile project for the future.

Literature

Aarseth, Mathilde Becker: Mosul under ISIS. Eyewitness Accounts of Life in the Caliphate, London 2021.

Arjona, Ana: Rebelocracy. Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. New York, NY 2016.

Kasfir, Nelson: Rebel Governance. Constructing a Field of Inquiry. Definitions, Scope, Patterns, Order, Causes, in: Arjona, Ana, Kasfir, Nelson, Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian (Hrsg.): Rebel Governance in Civil War, Cambridge/New York, NY 2015, 21-46.

Pfeifer, Hanna: Recognition Dynamics and Lebanese Hezbollah’s Role in Regional Conflicts, in: Geis, Anna Clément, Maéva, Pfeifer, Hanna (Hrsg.): Armed Non-state Actors and the Politics of Recognition, Manchester 2021, 148-170.

Pfeifer, Hanna, Schwab, Regine: Re-examining the State/Non-state Binary in the Study of (Civil) War, in: Civil Wars (im Erscheinen), 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2023.2254654.

Pfeifer, Hanna, Weipert-Fenner, Irene: Time and the Growth of Trust under Conditions of Extreme Uncertainty. Illustrations from Peace and Conflict Studies, ConTrust Working Papers 3, 2022, 1-14.

Revkin, Mara Redlich: Competitive Governance and Displacement Decisions under Rebel Rule. Evidence from the Islamic State in Iraq, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution 65:1, 2021, 46-80, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720951864.

Schwab, Regine, Massoud, Samer: Who Owns the Law? Logics of Insurgent Courts in the Syrian War (2012–2017), in: Gani, Jasmine K., Hinnebusch, Raymond (Hrsg.): Actors and Dynamics in the Syrian Conflict’s Middle Phase. Between Contentious Politics, Militarization and Regime Resilience, Abingdon/New York, NY 2021, 164-181.

Stewart, Megan A.: Civil War as State-Making: Strategic Governance in Civil War, in: International Organization 72:1, 2017, 205-226, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818317000418.

The author

Hanna Pfeifer is Assistant Professor of Political Science, especially Radicalization and Violence Research, at Goethe University Frankfurt and the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF). She also heads the research group on“Terrorism” at PRIF. Her research focuses on Islamist and jihadist actors, as well as state and non-state conflicts and order dynamics in West Asia and North Africa. Violence and terrorism are overrepresented in media coverage of the region. Western publics are less well-informed about the order-building activities of armed actors – and about the violent consequences of Western order-making. Hanna Pfeifer’s interest in these two perspectives was sparked by enriching encounters with people in and from the region.