If populism threatens order, perhaps the stubbornness of reason can help

by Olaf Kaltenborn

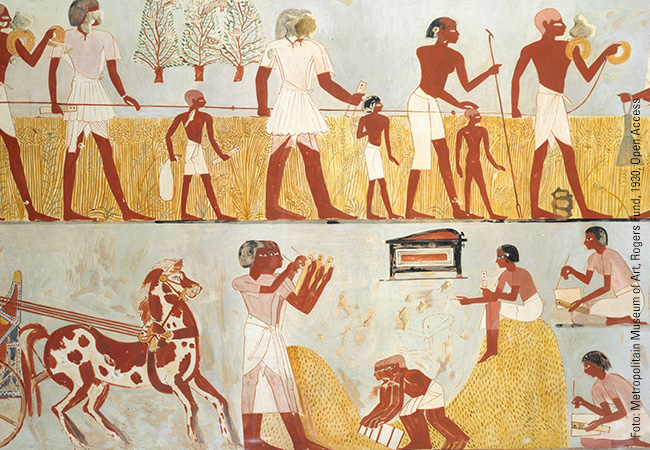

Order, order: The venerable Chamber of the House of Commons, home of the elected parliament of the United Kingdom.

Photo: picture alliance/REUTERS POOL/Justin Tallis

Orders govern our lives and how we live together in society. But what are orders based on? And how can we protect them?

John Bercow, former speaker of the UK’s House of Commons, earned himself an almost legendary reputation as a very vocal disciplinarian: “Order, order!” echoed his sonorous voice through the raucous House of Commons during the endless Brexit debates. His appeal was far more than just a call for more discipline.

The former speaker’s call for order protected the functioning of parliament and helped to validate it on many occasions. Bercow’s actions were legitimate by virtue of his office, and he was able to resolutely enforce order even in these difficult hours, some of the most difficult that this parliament steeped in tradition had experienced in decades. He appeared to some as the last guardian of parliamentary dignity in an otherwise often undignified game, as the embodiment of parliamentary and thus democratic order. But what exactly do we mean when we speak of “order”?

Order – one of the most universal and at the same time most normative terms – is difficult to grasp. As regulated and regulating contexts of meaning and function, we are familiar with orders and words derived from order: We speak of orders of thinking, normative orders, divine order, world order, political orders, economic orders and office orders; but also of calls to order, public order departments, order mania, sense of order, etc. There are many orders in religious, military and educational systems, and arbitrary orders from above issued over the heads of those concerned. We can see order at work everywhere, often intricately woven and interconnected, as a fine fabric of our social reality.

Orders are elastic

Orders are not rigid; they constantly evolve and often prove to be elastic in relation to the reality they regulate, but not always. That is why philosophy, political science, sociology, law and economics, to name just a few disciplines, repeatedly focus on the concrete and abstract regulatory contexts on which orders are based. Ordinary law is also constantly expanding to include areas that may previously have been extraordinary.

In the sense of rule-based individual and societal shoulds and coulds, orders can always be charged with new meaning and new justifications; they are extended and supplemented and, more rarely, deleted or revised; but they can also fail due to their own nature or the reality that they claim to regulate or justify: Normative claims to the validity of orders and their scope may be doubted; conflicts are sparked by partially competing or self-contradictory models of order; orders can then even become dysfunctional; sometimes the sovereign is threatened by the excessive regulatory frenzy of a legislator who does not stop at any area of our coexistence, and – in the worst case – sees themselves as the embodiment of all political order. Non-codified orders also govern our lives, giving them normative content, form and meaning and serving as orientation: Values, practices, customs, traditions, unwritten cultural practices and attitudes – they are all based on obscure patterns of order which, however, unfold a sublime potency – are often not recognizable to outsiders in their regularity and are therefore exclusive.

Ultimately, one of the most effective patterns of order is language: It gives our thoughts, which are invisible to others, an understandable, informative form. The world of linguistic symbols is one of the most effective and powerful patterns of order.

Order from a phenomenological perspective

Einer der Philosophen, die sich mit dem Begriff der Ordnung phänomenologisch gründlich auseinandergesetzt haben, ist der Philosoph Bernhard Waldenfels (zum Beispiel »Ordnung im Zwielicht«, S. 19–20): »Wovon grenzt ›die Ordnung‹ sich ab? Wonach richtet sich ›der Vernunftsgebrauch‹? Fragen wir so, so scheinen wir in ähnliche Schwierigkeiten zu geraten, wie wenn wir in der Sprache über sprachlose oder sprachfremde Erfahrungen verhandeln wollen. Wie in der Sage des Midas scheint sich alles alsbald in das Gold der Sprache zu verwandeln oder auch in das Gold des Bewusstseins, die Währungsart macht keinen großen Unterschied. Ähnlich also auch hier. Das Ungeordnete wäre das, was der Ordnung vorausliegt und zur Ordnung gebracht wird. Man kann schwerlich auf die Annahme eines Zu-Ordnenden verzichten, ohne die Ordnung in eine pure Idee, in eine reine Möglichkeit zu verwandeln, die von einem konkreten Ordnungsgefüge, einer Ordnungsstruktur nichts übrig ließe. Dennoch haben wir mit dem üblichen Einwand zu rechnen, der uns an nicht zu hintergehende Voraussetzungen mahnt. Indem wir das Zu-Ordnende bereden, betrachten und behandeln, bewegen wir uns bereits im Rahmen einer Ordnung, dahinter können wir nicht zurück, es sei denn um den Preis der Bewusst- und Kopflosigkeit. Wir können, so wie Kant seinen Rousseau verstand, »auf einen solchen Vorzustand zurücksehen, nicht aber auf ihn zurückgehen«.

Die Perspektive, die Waldenfels in der Tradition von Edmund Husserl und der französischen Phänomenologie eröffnet, enthält eine Irritation für das verbreitete und oben dargestellte Ordnungsdenken – insbesondere für die politische Philosophie und Politologie: Versteckt sich doch gleichsam in jeder Geltung oder Rechtfertigung ein unhintergehbarer Rest, der nicht zu rechtfertigen ist; genauer gesagt: Das Verstecken erfolgt in einem Raum, der der Geltung und Rechtfertigung gleichsam unbegründet vorausliegt. Das wirft die Frage auf, was denn Individuen, Kollektive und Rechtsgemeinschaften überhaupt dazu bringt, eine Rechtfertigung ALS Rechtfertigung zu respektieren und sie als FÜR SICH geltend anzuerkennen? Woher kommt diese Einsicht in die Notwendigkeit, der moralische Imperativ eines Sittengesetzes wie bei Kant? Lässt sich diese allein aus einer gleichsam überkulturell geltenden, regelbasierten Vernunft rechtfertigen? Oder gibt es nicht noch viele andere Möglichkeiten?

Here is an – incomplete – selection:

• From the individual conscience as an “inner judge”? Conscience is regarded as a non-reason-based “higher” authority with reference to any kind of “higher” or “divine” order, which, however, does not disclose the actual reasons for this order.

• From a reason-based insight into the recognition of an order that unites all? This presupposes an internal order of reason that unites all or an insight shared by all members of this order into the rationally justifiable reasons for this order.

• From the letters and the inner logic of the text itself? The assumption here is that the vigilant reading of a generally understandable normative text that is accessible to all can itself trigger a compelling inner force for recognition.

• From a traditional authority according to which we must abide by the law? In this case, recognition is based on a rather unreflected but effective legal authority, which is largely unquestioned by the subjects who feel they belong to an order.

• Out of fear of punishment and sanctions for non-recognition? This, as it were, “negative” insight and forced recognition do not result from “higher insight” (for example, reason, divine law), but from the fear of the sovereign imposing order on every subject under him or her, by force if necessary.

It is already evident from this cursory overview that orders – including political ones – often stand on a much thinner foundation than is commonly assumed, and they are bound in their effect and validity to conditions that they themselves do not (or cannot) contain.

This reservation and the associated risk of the backsliding or even failure of orders (which do not result from the rational reasons of these orders themselves) can be clearly seen in our initial example, the calls to order of John Bercow in the UK Parliament, who, like a tragic hero, a Don Quixote, tried to keep the Brexit debate in the House of Commons, which was toxic to democracy, in check. In the end, he stood little chance against a disorderly political populism based on lies and deception with the declared goal of Britain leaving the EU.

Political populism draws its explosive strength first of all from a growing lack of justification and legitimization (“by those at the top”) of existing (reason-based) forms of order, which it continuously disparages (along with these orders’ most important actors), foremost in the eyes of a minority, which is, however, gradually developing into an (apparent) majority. In doing so, it deliberately exploits the vulnerabilities of orders and their supporting actors as well as the open forms of discourse to its advantage, stokes “fears of over-foreignization” and “deep state fantasies” or spreads lies and “alternative facts” along with self-pitying utterances that its own position is being cancelled by left-wing “state media”. The growing and persuasive mass effect does not result from a verifiable truth, but from the hundredfold public repetition of such narratives. Populist ideologies, with their increasingly refined communication techniques, aim to undermine the arguments for reason-based political thought and action and thus at the same time to disrupt the legitimacy of the democratically elected political actors and, ultimately, the legitimacy of democratic orders themselves. The legitimacy of democratic orders and the institutions that support them sometimes emerge from this dramatically weakened – as in the USA after Trump, for example, but also in Poland, Hungary, Israel and Turkey – and similarly through former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his in some cases politically frivolous predecessors in the UK.

But what can our democratic order do to counteract corrosive populist currents and infiltration tendencies?

IN A NUTSHELL

• Orders are extremely complex. In every community or state, we have always lived – partly unquestioned – in a web of orders that overlap, complement and partly contradict each other.

• The article approaches these different dimensions of orders selectively and presents some of their entanglements.

• In the second part, the article focuses on the risks posed to democratic orders by an increasingly widespread populism. What can we do about it? Researchers are looking for answers, not least from Jürgen Habermas.

Here are several suggestions:

Assume more journalistic responsibility: Especially in the media, there is often the questionable practice of allowing unproven opinions and populist narratives on an argumentative level and equating them with factual and/or scientifically sound knowledge – for example in the climate debate. This practice – often due to time constraints and keeping ahead of the pack – should be reconsidered and corrected in the interest of disseminating knowledge that has been properly verified. Reasoning and fact-based verification is also a service to democracy.

Explain and classify better: Democratic politics should consider a change in political communication, which is often highly ritualized and stereotyped – traditional patterns of representation are perceived by many as detached, abstract and unrealistic. This wastes the opportunity to make people aware of democratic decisions and the backgrounds to them and to win them over to democracy. Perhaps we could learn from the populists and their undisputed narrative skills – and apply these responsibly against a vicious and corrosive populism.

Refute narratives: Continuously refuting populist narratives with arguments and facts is not only the constant task of journalism, non-populist politics and science. It is also the task of each individual not to remain silent when the occasion arises – in their personal environment too – but to take a clear and argument-based stand. The greatest tactical advantage, but also the Achilles’ heel of populists, is often the nimbleness and speed with which they divert discontent about current developments to their political grist. The appropriation of the peaceful East German revolution of 1989 by the Thuringian AfD chairman Björn Höcke is an example of this; the equating of the currently allegedly suppressed freedom of expression in Germany with the conditions in the GDR is another. In the context of “We did not demonstrate for freedom in 1989 only to have it taken away again by those now in power,” Höcke cannot claim to be part of the “we” – after all, he was a teacher in Hesse until September 2014. The inaccurate comparison is easy to refute: No one in Germany today has to fear state spying and prison sentences because of their political opinion, as was the case in the GDR.

More courage and “Now more than ever!”: Finally, let us consider Jürgen Habermas, who counters these worrying developments with a “Now more than ever!” that goes back to Kant. “(…) With few exceptions, the political elites allow themselves to be disarmed by an ideologically exaggerated social complexity and have lost the courage to shape politics. Meanwhile, national publics, dried up of almost all truly relevant issues, have turned into arenas of distraction and indifference, if not mutually fomented nationalist resentment. If we do not want to leave it at this gloomy diagnosis, we can learn at least one thing from a Kant enlightened by Marx: The mole of reason is blind only in the sense that he recognizes the resistance of an unsolved problem without knowing whether there will be a solution. But he is stubborn enough to continue burrowing forwards through his tunnels notwithstanding. Kant impressed this attitude on us at the same time as his insights – indeed, his philosophy consists of collecting good reasons for this attitude. And isn’t that the greatest thing about his magnificently enlightening philosophy?” (Jürgen Habermas, in: Forst, Rainer, Günther, Klaus (eds.): Normative Ordnungen, Berlin (Suhrkamp) 2021, p. 41)

Last but not least, extensive research is currently underway into how social conflicts can be resolved constructively and how society can be held together. Goethe University Frankfurt hosts two major projects on this topic: the ConTrust research initiative and a section of the Research Institute Social Cohesion, a national institute with a decentralized structure.

The Research Institute Social Cohesion

The Research Institute Social Cohesion (RISC), a decentralized organization spread over eleven locations, was founded on June 1, 2020. RISC’s spokeswoman is Nicole Deitelhoff, Professor of Political Science at Goethe University Frankfurt. Under the RISC umbrella, there are currently 83 research and transfer projects dedicated to social cohesion issues.

ConTrust Research Initiative

Trust and conflict are often understood as opposites. The cluster initiative “ConTrust: Trust in Conflict – Political Life under Conditions of Uncertainty” is based on the idea that trust only takes shape in conflicts. Sometimes, however, trust in certain people or parties stirs up conflicts or cements them. ConTrust investigates the conditions for settling social conflicts successfully.

The author

Dr. Olaf Kaltenborn, born in 1965, studied political science and journalism and was Press Officer at Goethe University Frankfurt until 2023.