The RISS project examines how social change affects established structures in education

by Katja Irle

Photo: Aleksandr Ozerov/Shutterstock

Globalization, migration, new gender relations, educational expansion: All this is changing our social structures. How does this change affect society and the individual? The RISS Research Unit (Reconfiguration and Internalization of Social Structure) of the German Research Foundation (DFG) is exploring these questions.

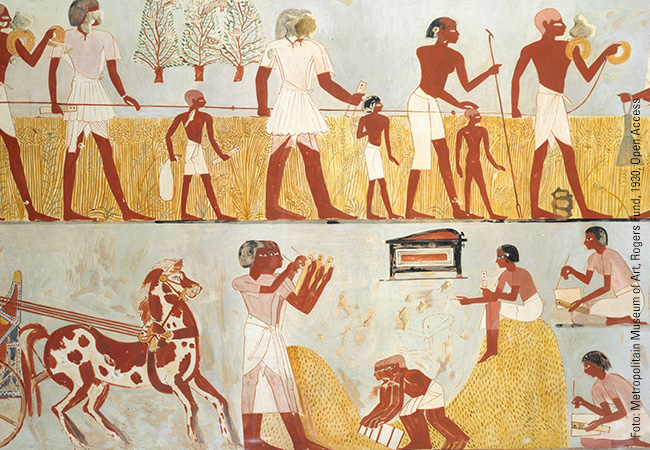

Things could be so easy if everything stayed as it used to be: 70 years ago, doctors in Germany were mostly white men who followed in the footsteps of their fathers. The system reproduced itself and with it the success of those representing a certain social class. Belonging to a social class, but also to a professional group or a religion, usually went hand in hand with certain political beliefs and corresponding voting behavior. Christians (especially Catholics) and farmers voted for the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) or the Christian Social Union (CSU). Trade union workers gave the Social Democratic Party (SPD) their vote. The self-employed voted for the Free Democratic Party (FDP).

This stereotypical thinking was oversimplified even back then and not always consistent. For social and political order, however, the predictability associated with it brought a certain stability. Due to processes of social change and the dismantling of social inequality, these social patterns and certainties have become increasingly fragile in recent decades. As social status and power relations shift, what might seem to be politically and normatively welcome can also result in uncertainty and new social conflicts. As a result, many things seem more uncertain, complicated and conflict-ridden than they did before.

Back to white German doctors: Today, around two-thirds of medical students are female. The proportion of physicians with a migrant background is increasing year by year. Without immigration, the health system would be on the brink of collapse, as the Expert Council on Integration and Migration recently stated. Like medicine, most other professions are also becoming more heterogeneous. The education system has seen and is still seeing an enormous expansion. After the prototypical educational rise of the Catholic girl from a rural working-class family described by Ralf Dahrendorf in the 1960s, more and more children and adolescents from lower social classes and a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds now attend higher level schools. More than a third graduate from high school. Student cohorts at universities are more and more heterogeneous each year, too. And this new heterogeneity calls into question the old, often ingrained “order” of institutions such as schools and universities, but also that of the labor market.

IN A NUTSHELL

• Socio-structural change leads to a shift in people’s social structural position and political orientation. On the one hand, there is more social permeability and participation. On the other hand, certain groups continue to be disadvantaged and there are new conflicts.

• The RISS project is investigating the impact of these changes: Does an increasingly heterogeneous society lead to more integration and unity?

Or does identification with the existing order decrease? What about political stability when old patterns and group affiliations disintegrate? What will take their place?

• The aim of RISS is to document and empirically analyze the complex multidimensionality of social change, social inequality, political participation and representation – and in this way better understand these processes.

Fundamental changes

“The changes we are experiencing are anything but marginal. They are so fundamental that they are transforming the social structure as a whole,” says Daniela Grunow, Professor of Sociology specializing in Quantitative Analyses of Social Change at Goethe University Frankfurt. She is spokesperson for RISS (FOR5173), a Research Unit of the German Research Foundation, which is currently tracking this multidimensional shift and its effects in six individual projects. “The crux is that people do not only have a gender, a migration status or a certain social class. They belong to many socio-structural groups at the same time, and the social mobility of recent decades has made it more difficult to reconcile associated identities and orientations.”

The RISS team wants to better map and understand this growing heterogeneity via a new analytical strategy. The researchers are using existing data, such as microcensus, the annual household survey, and Allbus, the German General Social Survey. In parallel, the teams are designing new surveys and currently collecting their own data in order to include larger samples of subgroups. For example, they are combining large representative samples of the German population with strategic oversampling, where one or more groups are deliberately overrepresented – such as young people with a migrant background or immigrants from certain countries.

This strategy is informed by an important insight: “Thinking in large, generalized groups and one-dimensional trends leads us down the wrong track,” says Daniela Grunow, who is the RISS spokesperson together with her colleague and co-spokesperson Professor Richard Traunmüller from the University of Mannheim. “It is often assumed, for example, that immigrants are more traditional than Germans and that this is the reason why immigrant women are less likely to work. But this is a very sweeping statement that lacks truth.” Differentiated analyses show that people of German origin also have heterogeneous orientations and that most immigrant groups do not differ from Germans much at all when it comes to female employment.

Impact on identity

Foto: Jan Hering

The comprehensive data collected in the RISS projects provide the basis for answering a core research question – namely, how socio-structural shifts affect people’s identities and coexistence overall: How does individuals’ disposition to attach themselves to social groups change? Are new forms of social integration being established? What happens if the concept of educational climbers and non-climbers no longer fits into the classic pattern? Does a working-class child with a university degree still feel part of a lower social class? Or rather of the educated middle class? Does the relationship of educational climbers with a migration background to their family of origin change? And how do these upheavals and contradictions affect the self-efficacy of individuals – their belief that they can also master difficult situations by themselves?

Sociologist Birgit Becker is looking for answers to these questions. She is Professor of Sociology with a focus on Empirical Educational Research and coordinates RISS project 3, together with her colleague Sigrid Roßteutscher. The project deals with the participation of young people in education and politics. Their team is investigating what role the experience of self-efficacy plays for young people in the school system and whether beliefs formed there can be transferred to the political sphere. Put simply: Does a young person who experiences teachers or school overall as unjust distrust the political system?

“School is a central institution: Young people not only spend a lot of time there but also gain initial experience of how they and their group are treated in the system,” say Birgit Becker, describing the research approach. She is interested in young people’s idea of what they can achieve as individuals, as members of a particular social group and within the social system – or else not. The RISS team is looking above all at status inconsistency: “Stratification is not as clear as it used to be. Historically disadvantaged groups are rising up through the educational ranks, and, conversely, young people from academic families are breaking away from conventional expectations, for example if they do not graduate from high school. We want to find out what happens in young people’s heads when historical contexts are no longer stable, but instead changing or even disintegrating.”

To do this, Birgit Becker and her team compare young people from different types of schools. They also use oversampling to include enough young people with a migration background in the study. Through online surveys, the Research Unit wants to find out more about which identity features play a special role for young people (such as ethnicity, social class or religion) by integrating fictitious characters. The RISS team is interested in how similar young people feel to a fictitious person and whether they believe, for example, that the person will succeed in school or politics. With the help of this method, the scientists assess which aspects of identity are important for the respondents and what significance they have for their self-image.

Success and failure in educational biographies

How young people deal with success or failure in their educational biography is a fascinating question in this context. Do historically disadvantaged groups tend to associate poor grades or school-leaving qualifications with discrimination based on their ethnic or social origin – or do they feel it is more of a personal failure because they didn’t study hard enough? Is something changing here because educational expansion is shifting classic explanatory patterns? How does the traditionally advantaged son from an academic German family justify not being able to achieve the grades at school required to study medicine? And: Do young people develop a general systemic mistrust or confidence in the state and its institutions, depending on their experiences in their educational biography?

Another step will be to investigate how the institutions themselves are reacting to this change. Will they be able to do justice to the changing situation? Birgit Becker has already examined a partial aspect of this question in another joint project between Goethe University Frankfurt and the Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education (DIPF), which investigates changes in schools due to flight and migration since 2015. As expected, the results do not show a uniform picture but a wide range of reactions: “Especially schools in rural areas or the few general secondary schools that still exist saw immigration as an opportunity to survive. They were motivated, they changed and they adapted to the new student cohort,” says Birgit Becker. A different picture emerged, for example, in schools in large cities: “They often found that admitting refugees was an additional burden.”

It is to be expected that Birgit Becker and Sigrid Roßteutscher’s joint project, as well as the other projects of the RISS Research Unit, will provide complex insights rather than a simple narrative. But it is already clear that yesterday’s compartmentalized thinking is no longer suitable to grasp the complexity of today’s and tomorrow’s society.

The author

Katja Irle, born in 1971, is an education and science journalist, author and facilitator.