Architectural metaphors in the language of democracies often have little in common with reality

by Carsten Ruhl

Photo: katuka/Shutterstock

Why is there so much talk of “architecture” in politics?

Why cannot architecture itself be democratic?

Architectural historian Carsten Ruhl has given it some thought.

Building a tower from single blocks is not so easy. There are many games where children and their parents encounter this: Mounting brick upon brick without the pile collapsing requires care, concentration and a steady hand. Nobody wants the blame for the tower collapsing or to be the biggest loser ever. That would mean personal defeat, destruction of collective work and a proven lack of skill. The other players, on the other hand, can pride themselves on being the adept builders of a fragile – but for that reason all the more admirable – structure.

Sometimes, offices and institutions in Germany also seem to believe that they belong to this group. The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), for one, apparently considers itself a member. At least the Office’s website gives that impression. Under the heading “The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees as part of Germany’s security architecture”, there is a rather telling picture: With obvious determination, a man – the tie identifies him as an Office employee – places a wooden building block on the neatly stacked tower. So that no one is in any doubt whatsoever about how secure this tower is, the Office drives the point home with another architectural metaphor, this time in the caption. It describes itself as an important “pillar” of Germany’s security architecture. How should we interpret this wording in conjunction with the heading? The Office presents itself as a building block of a national “security architecture”, which, according to its own self-image, still succeeds in steering everything in an orderly fashion even where order has long ceased to exist. It is commonly known that migration to Germany and Europe is not static, as especially the image of the pillar would like to suggest, but instead dynamic and unpredictable. Not to mention the alarming effect that this manifestation of the bureaucratic governance of human destinies can have.

The word “architecture” in political jargon

A brief look at how bureaucracies and institutions present themselves raises the following questions: What function does the word “architecture” perform in political discourse and what does this mean, in turn, for the architectural representation of democratic states? Let’s stay with the term “security architecture”. Its frequent use in the language of German politics over decades only partially reflects any special appreciation of building culture. It is rather the case that architectural terminology is used metaphorically in political speeches about the security of Germany or Europe. But how is the word “architecture” used as a political metaphor? What role does this metaphor play in political practice? And what does this, in turn, mean for the architecture of a democratic society?

At the end of the 20th century, a certain unease began to spread in politics in view of the wide and growing use of the word “architecture”. In his opening words at an OSCE conference, political scientist Heinrich Schneider remarked that the undifferentiated use of this term bore no relation to its complexity (Schneider, 1995). Going back quite a long way in the history of ideas, Schneider reminded the audience that Aristotle had understood politics as an architectonic art, for example, and that Kant had defined “architectonic” as the construction of a rational system. In Schneider’s opinion, anyone who refers to the status quo of European security policy as a security architecture completely ignores this aspect of the word’s meaning. In view of the many unresolved problems in Europe, we could at best speak of an “insecurity architecture”, he said. In other words, for Schneider, the promise of order signaled by the term “security architecture” bore no relation to the disorder that actually prevailed. From this perspective, the “common European home”, another metaphor Schneider brought into play, was nothing more than a construction site.

Architecture? Or infrastructure?

Schneider was reflecting on a development he could see in the remarkable career of the word “architecture” in politics. The historical background to his observations was the gradual end of the systemic rivalry between West and East – and thus also the end of definable borders between political spheres of influence that could have been cited as a concrete threat to one’s own security. Security was no longer a necessity linked to a specific military threat. Rather, it was based on threat scenarios that were more abstract and no longer called for a solely military response. Security – from today’s perspective we would in truth have to speak rather of the illusion of security – could be established, for example, by creating mutual economic dependencies (“Change Through Trade”). The architecture metaphor compensated to a certain extent for the absence of a physical and material security infrastructure.

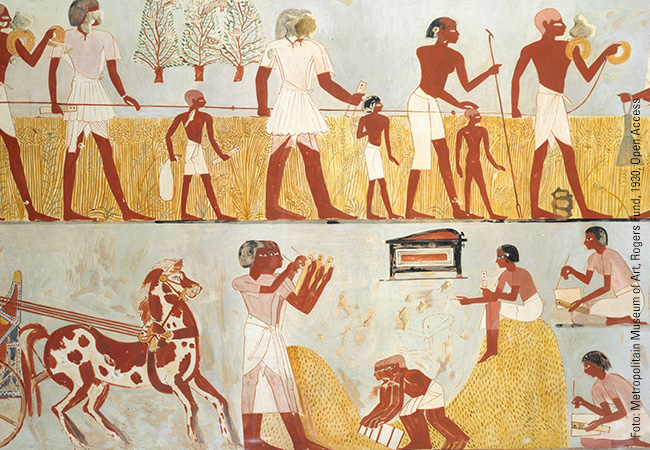

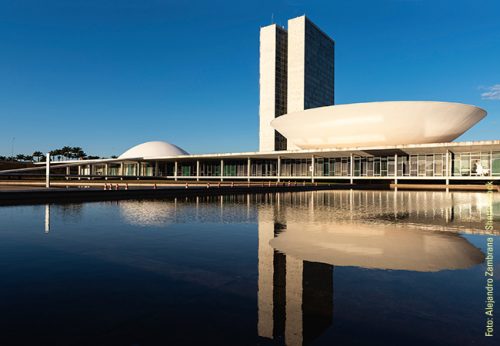

The potent image here of architecture as the quintessence of rationality, permanence, logic, equilibrium, reason and professionalism still seems to correlate to the self-image of political elites today. Its usefulness for democratic culture, on the other hand, is rather dubious – at least if we understand democratic order not as a rigid construct but as a practice that must be adaptable and flexible within certain boundaries. If we take the definition of democracy seriously that political scientists have recently called “institutionalized uncertainty”, then order here does not mean a static construct but a permanent process of negotiation. The image of architecture, by contrast, serves above all to cover up these uncertainties, to feign permanence and equilibrium where in fact adaptability, dynamism, negotiation and processualism ought to prevail. This would be unproblematic if, in so doing, the political elite would not delegitimize – consciously or unconsciously – the democratic order it claims to protect. After all, “real” architecture is rarely the outcome of democratic decision-making processes. Not even when, as in Brasília, it is considered the quintessence of democratic architecture (Pohl/Ruhl, 2023). Architecture is therefore only suitable as a metaphor for a “real” democracy and its institutions to a limited degree. To speak of a “building of democracy” is misleading – but so, too, is the assumption that a specifically democratic architecture exists.

Untransparent systems also like transparent buildings

Even if a connection between political and architectural transparency is fondly posited in political speeches, it is better to speak of architectures in democracies than of architectures of democracy, not least because there are valid historical reasons. With regard to the analogy between transparent buildings and a transparent political system, it can be noted that even the Italian fascists back in the 1920s to 1940s considered transparent glass façades to be a suitable means of architectural representation. After all, glass enables us not only to look in but also out, giving us a panopticon of public space in the Foucauldian sense. By contrast, most democracies either had to make do with the architectural relics of previous regimes or even actively fell back on architectural resources from pre-democratic times (Minkenberg, 2020). Striking examples include Washington D.C. with its monumental axis stretching between the Potomac and Anacostia rivers, but also the Reichstag building in Berlin, whose architectural and historical heritage can be traced back to royal residences. The seat of France’s National Assembly is a palace on the Place de la Concorde built for the Duchess of Bourbon in the early 18th century.

None of this is intended to be a plea for a new arbitrariness in the way democracies express themselves through architecture. Rather, the aim is to direct attention to the neglected complexities of architecture both as a metaphor and as a built object. Contrary to popular belief, the architectural project alone is not the main thing, but instead merely the interface between two spheres of architecture that establish order and are thus eminently important for the acceptance of democracies. If Winston Churchill was right when he said about architecture: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us,” then clearly the conditions for the production and reception of architecture are highly significant for its perception as a “symptom” of democratic systems. The attempt to objectify democracy with the help of architectural metaphors ignores this fact because all the dynamics that should actually characterize democracy are also metaphorically cast in stone.

This raises important questions that need answering again and again and lead right to the crux of how democracies and their architecture see themselves. Who makes the architectural decisions? How is architecture orchestrated? How, in turn, does it orchestrate our co-existence? How can planning processes be shaped democratically so that the results are seen in the first place as democratic architecture by as large a part of society as possible? The brick that topples the tower would then be a sign not only of weakness but also of sovereignty. Perhaps even the sovereignty of the people. At least, however, it could always prompt a new game in which all the players must show that they are good losers. What could be more democratic?

Literature

Minkenberg, Michael: Demokratische Architektur in Demokratischen Hauptstädten: Aspekte der baulichen Symbolisierung und Verkörperung von Volkssouveränität, in: Schwanholz, Julia/Theiner, Patrick (Hrsg.): Die politische Architektur deutscher Parlamente, Wiesbaden 2020, S. 13-39.

Müller, Jan-Werner: What (if Anything) Is »Democratic Architecture«?, in: Bell, Duncan/Zacka, Bernardo (eds.): Political Theory and Architecture, London/New York 2020, p. 21-37.

Pohl, Dennis/Ruhl, Carsten: Brasília oder London? Regierungsarchitekturen zwischen Ordnung und Konflikt, in: Heß, Regine (Hrsg.): Architektur und Konflikt, Kritische Berichte, Heft 2, 2023, S. 78-92, https://doi.org/10.11588 kb.2023.2.94662

Schneider, Heinrich: Sicherheitsarchitektur Europas, in: Sicherheit und Frieden (S+F)/Security and Peace, Vol. 13, No. 4, 20 Jahre nach Helsinki: Die OSZE und die europäische Sicherheitspolitik im Umbruch (1995), pp. 226-230.

About Carsten Ruhl

Carsten Ruhl is Professor of Architectural History at the Department of Art History, Goethe University Frankfurt. After graduating from high school, he initially studied architecture in Dortmund before switching to art history, philosophy and history at Ruhr University Bochum. Architecture remained his passion: After completing his Master’s degree in art history, he was a scholarship holder of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) in London as well as of the Gerda Henkel Foundation and completed his doctoral degree with a dissertation on the English architectural discourse of the early 18th century. His habilitation thesis dealt with an Italian architect of the modernist period. He was a professor at Ruhr University Bochum and Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. Ruhl is spokesperson for the LOEWE research initiative “Architectures of Order”.

About the author

Andreas Lorenz-Meyer, born in 1974, lives in the Palatinate and has been working as a freelance journalist for 13 years. His areas of specialization are sustainability, the climate crisis, renewable energies and digitalization. He publishes in daily newspapers, specialist newspapers, university and youth magazines.