How bacteria cope with environmental stress

by Andreas Lorenz-Meyer

Photo: matteo_it/Shutterstock

Biochemist and microbiologist Inga Hänelt is investigating how bacteria transport potassium, an element vital for all living cells, through their cell membranes – even when environmental conditions are extremely unfavorable.

They are everywhere – in the sea, in the soil, in the air, in hot springs, on our skin and in our intestines: bacteria. That these unicellular organisms can colonize such a wide variety of habitats might seem astonishing. After all, in multicellular organisms such as humans, the cells inside the body are protected by the skin, the blood buffer and mucous membranes. In addition, constant temperatures are always ensured – something that bacteria can only dream of. Heat, aridity, acids and salts attack their cells mercilessly and with full force, as they are only separated from the sometimes harsh outside world by a wafer-thin shell – the stabilizing cell wall and one or two cell membranes. Bacteria have to be tough!

Inga Hänelt, from the Institute of Biochemistry at Goethe University Frankfurt, is investigating the mechanisms that bacteria have developed through evolution to enable them to react flexibly to challenging environmental conditions. Specifically, she is studying how membrane transport proteins facilitate the transportation of positively charged potassium ions (K+) into the cell. Why do they do this? Because bacteria need potassium ions to activate various protein complexes, to control acid concentration (pH value) and to regulate their salt and water content, a process known as osmoregulation. If the potassium ion balance goes awry, i.e. if the salt or water content is too high or too low over a longer period of time, the outcome is fatal. This is why bacteria have a kind of multi-stage crisis management system. “They have different transport mechanisms for different environmental conditions, which can be specifically switched on and off or formed anew and then disassembled again,” says Hänelt.

The power of the electric field

Here, an ingenious system of channels and pumps sees to a higher potassium concentration inside than outside the cell, is higher than outside, and even allows potassium ions to flow inwards against the concentration gradient. An electric field, known as the membrane potential, which the bacteria create through cellular respiration, helps them to do this. The cellular respiration apparatus obtains energy from the transport of electrons through several of its components. The energy is used to transport protons, i.e. hydrogen atoms that have released an electron, through the membrane to the outside. As a result, the cell interior loses positively charged particles and is therefore negatively charged – this is how the membrane potential is created. If the bacteria then need a fresh load of potassium, they open their potassium channel and the potassium ions are immediately drawn into the cell by the inwardly directed electrical gradient, even though the chemical potassium concentration is higher inside than outside.

One of the potassium channels in bacteria is called KtrAB. This protein remains active as long as bacteria are not under major stress and allows the inflow of potassium ions as required. It is activated via metabolic products (metabolites), which reflect the intracellular potassium ion level, among other things. However, as soon as things become uncomfortable, for example in an acidic environment, the potassium ion concentration must be directly and quickly controlled. The potassium channel KtrAB then downs tools and the transporter KimA takes over. KimA reacts immediately to the intracellular potassium ion concentration. As a secondary active transporter, it uses an existing chemical gradient, which forms because the concentration of protons in an acidic environment is higher than inside the cell, where the environment is neutral. The abbreviation “pH” comes from the Latin “potentia hydrogenii”, i.e. “power of hydrogen”. The protons give the potassium ions a piggy-back into the cell, as it were.

Trickery with oncentrations

Among the bacteria provided with valuable services by KimA is Bacillus subtilis, which is found above all in soil. When such a soil bacterium is present in an acidic soil with a pH value of 4, for example, the proton concentration around the cell membrane is one ten-thousandth (104) of a mole per liter. Inside Bacillus subtilis, by contrast, a neutral environment with a pH value of 7 prevails, or one ten-millionth (107) of a mole per liter. This means that there are a thousand times more protons surrounding the bacterium than in the bacterium itself – the gradient that KimA needs to transport potassium ions. The bacterium “smuggles” potassium ions through the cell membrane together with the protons. Although there is a counterforce, the outward potassium ion gradient, which exists because the potassium ion concentration inside the cell is considerably higher (150 to 200 millimoles) than outside it (normally around 5 millimoles), KimA uses the much stronger inward proton gradient to transport potassium ions into the cell. In this way, Bacillus subtilis can easily replenish its potassium ion supply in an acidic environment.

Survival in salt lakes

Then there is a third mechanism, which in turn is activated by other stress factors. It comes into play at low potassium concentrations, among other things. “Even at extremely low concentrations in the micromolar range, transport into the cell interior is possible,” says Hänelt. It also keeps the bacteria alive if there is severe drought or hyperosmotic stress, such as in a salt lake. The protein KdpFABC is responsible for this third mechanism. The letters FABC represent four proteins, of which A and B are essential for the transport of potassium ions.

Hänelt has discovered something in KdpFABC that no one previously considered possible. The protein is not just a transporter, but a channel and a transporter in one: “A cellular chimera,” she says, referring to the human-animal hybrid from Greek mythology. The process is as follows: Protein A, the channel, is selective, i.e. allows only potassium ions to pass through. Potassium is bound and passed on to protein B within the overall complex. This is not a secondary active transporter like KimA, but a primary active one. What this means is that it produces the energy it needs as a transporter itself by splitting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and phosphate – it thus acts as a pump. Protein B in KdpFABC belongs to the same family as the sodium-potassium pump, which in humans works at the cell membrane and supports sodium and potassium homeostasis.

Bacterial transport management

Many bacteria possess all three mechanisms, for example Escherichia coli, a bacterium that aids digestion in the human intestine. Outside the intestine, it is the most common pathogen for bacterial infections in humans. However, channel, transporter and pump alone are of little use to the bacteria if there are no regulatory instances that start the processes and then stop them again at the right moment. If, for example, KdpFABC were to continue pumping incessantly although there has long been sufficient potassium, this would poison the bacterium. That is why Hänelt is now also studying the controlling mechanisms for KdpFABC in greater depth. One pump regulator has been known for some time: histidine kinases. These enzymes notice a looming potassium deficiency and trigger protein synthesis. Once the situation has eased, they switch off gene transcription again because new pumps are no longer needed. But what about the pumps that have already been installed? “Once the bacteria have absorbed enough potassium, they must cease activity again quickly,” says Hänelt. For this, the bacteria have a second regulatory option, a kind of ‘off’ switch that is operated by other enzymes, called serine kinases. “This is how the potassium pump that is still running can be stopped immediately.”

What is Inga Hänelt planning to do next? Take a closer look at biofilms, i.e. the three-dimensional slime layer composed of sugars and proteins in which many bacteria come together and embed themselves. “Biofilms are almost like tissue. The outer cells protect the inner ones, in this way helping the community to survive,” explains Hänelt. Because when the chips are down, only the bacteria on the outside die and the ones inside can multiply again. It is already known that electrical signals propagate in biofilms, which the single-celled organisms use to communicate with each other. However, there are still many unanswered questions here, which is why Hänelt would like to find out exactly how this communication works, for example when the bacteria inside the biofilm are starving because not enough of the nutrient glutamate reaches the inside of the biofilm. According to a current hypothesis, they then allow the outflow of potassium ions, which causes the cell interior to become more negatively charged, and glutamate – coupled to proton inflows – can then be better absorbed. At the same time, the potassium ion outflows ensure that the neighboring bacteria located further outside are less negatively charged so that these absorb less glutamate, which is then available for the inner cells. As it is now the neighboring cells which are starving, they in turn release potassium ions. In this way, the signal propagates further and further to the edge of the biofilm and manifests itself in the fact that the growth of the outer cells stops.

“What we have here is a process that is similar to the transmission of electrical signals in nerve cells, for example, except that it occurs much more slowly,” explains Hänelt. She says that the communication function could be the reason why there are certain potassium channels in bacteria in the first place. Hänelt: “That is my main goal, to be able to describe how this communication works at the molecular level and to link this with the cellular level, that is, how the cell reacts as a whole.”

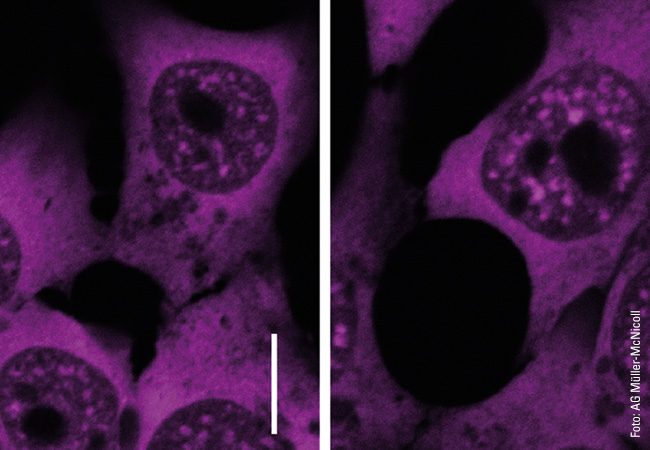

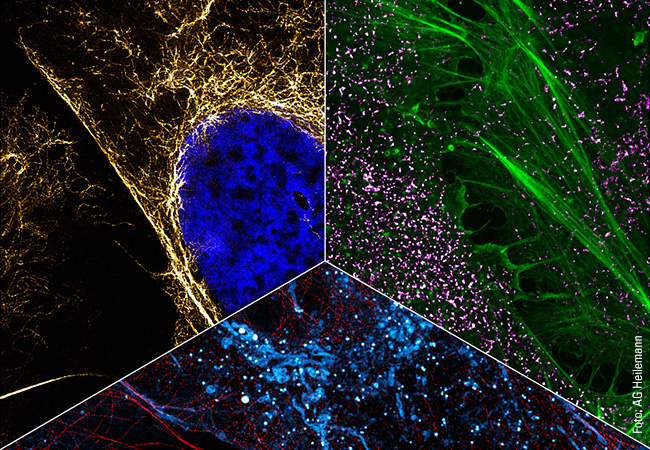

Digital twin

Hänelt is also involved as a spokesperson in the interdisciplinary research cluster SCALE, which is applying for funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) as a Cluster of Excellence. Its aim is to incorporate all the data collected and measured on a wide variety of three-dimensional molecular structures and their functions into the model of a digital twin, a vast database in which research data can be sorted and stored. To simulate cellular functions and reactions, the data are also linked with each other. “With the digital twin, we also want to look at the spatial distribution of proteins in a cell at a specific point in time, for example,” explains Hänelt. “How do proteins get to where they are needed? How do two proteins find each other and interact? How must molecules work together so that the intracellular structures and forms can develop?” The aim of the digital twin is to deliver hypotheses that can in turn be tested in experiments. It should also be able to simulate malfunctions and diseases triggered by mutated proteins, for example.

Hänelt is also counting on the digital twin’s support to understand potassium transport in bacteria. “So far, we have only looked at individual proteins. Now we want to investigate how the bacteria’s entire cell envelope reacts to osmotic stress. What happens, for example, in the first milliseconds after a salt shock when water flows out and is not yet retained by absorbed potassium ions?” Hänelt hopes her cell membrane research might one day unveil targets for new active substances against pathogenic bacteria – once the potassium transport mechanisms have been elucidated enough to be able to modify them systematically.

About Inga Hänelt

Inga Hänelt has been Heisenberg Professor for Membrane Biochemistry at Goethe University Frankfurt’s Institute of Biochemistry since 2021. After studying biology and completing her doctoral degree at the University of Osnabrück, she was a scholarship holder of the German Research Foundation (DFG) at the University of Groningen, Netherlands, and then a postdoctoral researcher in Frankfurt in 2012/13. In 2015, she took up a position as Emmy Noether Junior Research Group Leader and Junior Professor at the Institute of Biochemistry. Hänelt is co-spokesperson for the SCALE (Subcellular Architecture of Life) cluster initiative.