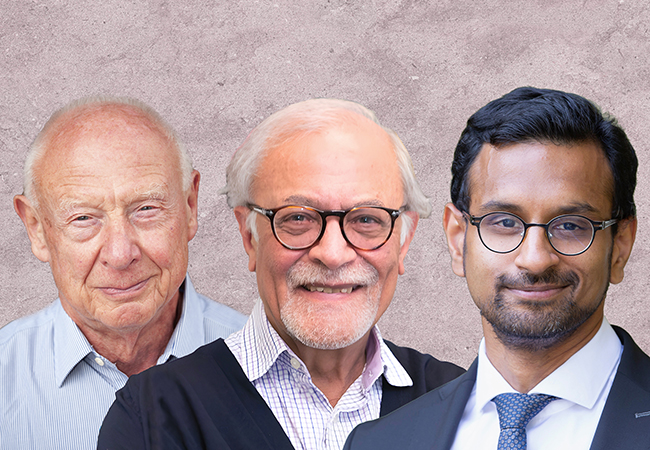

Goethe University legal scholar Prof. Alexander Peukert helped develop copyright rules for the EU’s first General-Purpose AI Code of Practice.

It’s been nearly three years since ChatGPT changed the world. The use of AI has since become part of everyday routine for many university members. Answering questions, translating texts, analyzing data, writing code, generating images and videos – the applications and potential of AI seem limitless. However, the risks associated with it are just as diverse. AI can provide instructions for building bombs, make false claims, engage in unlawful discrimination, and – of particular interest for this particular article – come into conflict with copyright law. The EU responded to these challenges both early and comprehensively by introducing Regulation 2024/1689 on Artificial Intelligence, the purpose of which is twofold: to foster the introduction of AI and support AI innovations, while also ensuring a high level of protection against the harmful impacts of AI within the EU. Ultimately, the regulation aims to ensure that only “human-centered” and “trustworthy” AI reaches the market. To achieve these ambitious yet abstract objectives, the AI regulation includes provisions for numerous subordinate rules that will further specify the requirements AI must meet to comply with EU standards.

Independent Working Groups

These regulations include a “Code of Practice” designed to clarify the obligations of providers of foundational AI models, such as the Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT), which underpins the ChatGPT system. The Code is no formal EU law but rather a co-regulatory instrument developed through a unique twelve-month process in which Alexander Peukert, Professor of Civil Law, Business Law, and Information Law at Goethe University’s Faculty of Law, played a key role. The European Commission did not draft the Code of Practice itself or leave it to AI providers to self-regulate but instead delegated the task to independent experts who led three working groups focused on transparency rules, managing systemic risks, and copyright law aspects of AI. Peukert co-headed the working group on copyright-related issues together with a legal scholar from the University of Ottawa. The goal was to determine what internal compliance rules an AI model provider must implement to ensure its models align with EU copyright law.

Work on developing the Code of Practice began in July 2024 with a public consultation, during which stakeholders were invited to share their perspectives on the appropriate level of regulation. Over 400 AI providers, copyright holders, researchers, and relevant NGOs participated. Additionally, the EU’s newly established European AI Office organized online workshops where stakeholders could present their key demands orally and ask questions of the working group leaders. Based on this input, the Commission published the first draft of the Code in November 2024. Two subsequent drafts followed shortly before Christmas and in March 2025, each preceded by written consultations and workshops. Meetings were also held with members of the European Parliament and the European Artificial Intelligence Board, which includes representatives from EU member states. As the process progressed, the draft authors received numerous requests from AI providers and other stakeholders to discuss specific details of the Code of Practice in bilateral meetings. The European AI Office encouraged these background discussions, and indeed, several meaningful clarifications were achieved in this setting. However, given the risk of undue influence and the potential reputational damage associated with it, Peukert maintained a public diary listing the dates, participants, and topics of all bilateral meetings he conducted. This diary remains accessible on his website.

Need for Intensive Coordination

The Code of Practice’s final version was published on July 10, 2025, two months later than originally planned. The delay was primarily due to the intensive coordination required between the draft authors on one side and the European AI Office as well as other Commission departments, including that for copyright law, on the other. The Commission’s influence on the Code, which can hardly be overstated, stemmed partly from its authority over the process. No draft was made public without prior coordination involving the Commission’s hierarchy, which provided detailed feedback in some cases. Additionally, the Code of Practice needed the Commission’s and member states’ approval under the AI Act to have any legal effect. The corresponding resolution on the Code’s adequacy was published one day before the legal principles came into effect on August 1, 2025. At the same time, the Commission announced that 26 AI model providers, including major U.S. companies like Amazon, Google, IBM, Microsoft, and OpenAI, will rely on the Code of Practice to provide proof that they are complying with their legal obligations under the AI Act. Their signatures grant them a certain level of trust with the Commission’s European AI Office, which will primarily examine whether the signatories are indeed adhering to the Code, while other companies must comprehensively demonstrate how their models meet EU requirements, including those related to copyright law.

Now that work on the Code of Practice has successfully concluded, its impact on the globally operating AI industry will be closely monitored. The copyright rules contained in it certainly preclude a Wild West approach, which seems to have been widespread in the past, when content from well-known piracy sites was at times even deliberately used to train AI models. It is also worth noting that the signatories have committed to moderating AI output to reduce the risk of copyright violations. Alexander Peukert will now follow further developments from his usual role as a scientific observer and has already completed the first academic article on the Code.

Further information on the General-Purpose AI Code of Practice →