Diamonds are witnesses to our planet’s transformation billions of years ago

Whereas the lava tends to overflow from the crater when Mount Etna erupts, it seems that during the rare kimberlite eruptions in the geological past the magma shot upwards at up to 250 kilometers per hour, propelling diamonds from great depths as it went. Photo: Fernando Privitera, Shutterstock

Over four billion years ago, oceans of hot magma shaped Earth’s surface. As our planet gradually cooled down, crusts formed in some places, and later the first continents. Rock samples and state-of-the-art analysis techniques are enabling geoscientist Dr. Sonja Aulbach to study the processes which took place during that period.

When particularly pure, large and famous diamonds change hands, the buyer usually has to shell out several tens of millions of euros. And diamond jewelry is highly popular as a glittering eye-catcher. Rather baffling, then, when a woman says: “What’s really valuable about diamonds is their mineral inclusions.” You mean, those same impurities that significantly reduce a diamond’s value when it comes to cash?

Sonja Aulbach, whose words these are, sees the gemstones through the eyes of a researcher. And the foreword of a current scientific anthology, which fills a massive 845 pages, shows the scientific view of diamonds and the minerals encapsulated in them: according to the book, the inclusions are “ambassadors from another time and another place”, much like “lunar rocks, extraordinary meteorites, samples from comet flybys or asteroid landings”. The inclusions deliver information “that we will not obtain in any other way” about the past of “the most dynamic and active terrestrial planet in our solar system, our Earth”. Sonja Aulbach from the Department of Geosciences at Goethe University Frankfurt is among the authors of this anthology, which also includes her own research results.

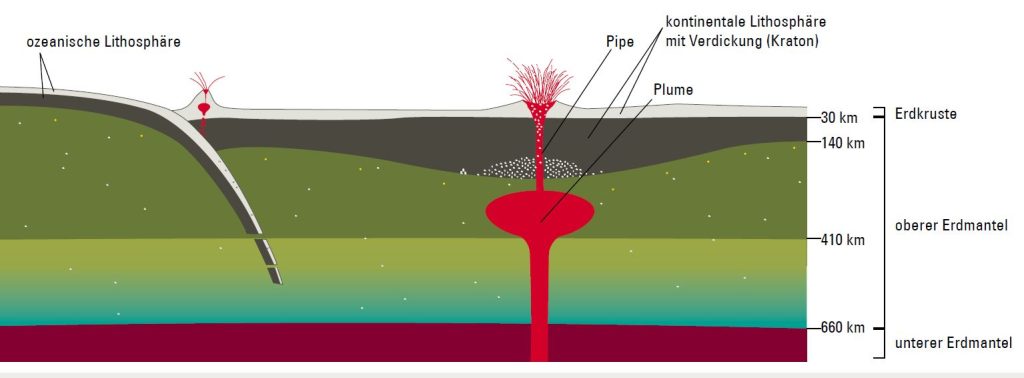

Gem-quality diamonds are only found in certain regions of continental nuclei where there are no earthquakes. Geoscientists refer to such regions as cratons. And within these cratons, they occur only in a particular kind of igneous rock known as kimberlite. The close link between diamond deposits and cratonic kimberlites is the starting point for many insights into Earth’s childhood. We know from laboratory experiments that producing diamonds from carbon at a temperature of 950 to 1400 °C requires a pressure at least 40,000 times higher than atmospheric pressure. Such conditions still prevail today at a depth of over 100 kilometers in the rock of Earth’s upper mantle. For this to happen, however, only a minimal amount of oxygen can be present, otherwise carbon dioxide (CO2) will be produced instead of precious stones. Furthermore, at this depth, only one in every 10,000 atoms is a carbon atom, so it is rather the exception that diamonds form there. Even if it were to happen more frequently, diamond prospectors would not be able to get their hands on the gems: no drill has yet penetrated deeper than twelve kilometers into Earth’s interior.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Inclusions in diamonds reveal that they formed up to 3.5 billion years ago. This makes them much older than the explosive magma that brought them to the surface.

- According to analyses, there was already land above sea level three billion years ago, and a kind of carbon cycle existed that was important for the origin of life.

- At the high oxygen content in Earth’s uppermost mantle, diamond is transformed into carbon dioxide, which enters the atmosphere together with magma.

Determining age

To be able to rely on diamonds found in mines as witnesses to earlier epochs of Earth’s history, we need to date their formation. To do this, geoscientists make use of the fact that some chemical elements also occur in unstable radioactive variants – radioactive isotopes. These decay at a certain rate into isotopes of other elements, referred to as daughter isotopes. We know, for example, that half of the original amount of the parent isotope samarium-147 is still present after 106 billion years because the daughter isotope neodymium-143 formed from the other half. If we know the decay rate, we can calculate a rock’s age from current isotope ratios.

Scientists can use mass spectrometers to measure the isotopic composition of a rock because isotopes differ in their mass. “I have access to the state-of-the-art equipment at the Frankfurt Isotope and Element Research Center (FIERCE),” says Aulbach, who is conducting her research with the help of a Heisenberg fellowship from the German Research Foundation.

The mineral inclusions in these diamonds, which are only three to four millimetres in size, reveal their age and allow conclusions about how Earth’s huge rock slabs formed. Photo: Sonja Aulbach

Isotopic dating by geoscientists worldwide shows that the kimberlites found so far – apart from just a few exceptions – formed no more than 550 million years ago.

It is not possible to determine the age of pure diamonds in kimberlite directly because they are composed entirely of carbon which has no isotope that decays sufficiently slowly. This is where the inclusions in the diamonds come into play: “They contain suitable isotopes,” says Aulbach, who has contributed to such dating work. According to this, the inclusions are up to 3.5 billion years old, depending on where the diamonds were found. The diamonds, together with their inclusions, are therefore mostly far older than the kimberlite magma in which they are entrained.

Diamonds can only form at depths lower than 140 kilometers (white dots). Because of the higher temperature and the greater chemical potential of oxygen in the convecting mantle (olive green), diamonds oxidize to become CO2 (yellow dots). That is why diamonds primarily occur in ancient continental nuclei (cratons), which have a thick and cold lithosphere.

These diamonds reach the surface via kimberlite eruptions: warm and chemically enriched mantle material (the plume) rises in a solid state to below the lithosphere, where it forms a certain amount of liquid magma due to the lower pressure (kimberlite melt). Gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapor cause the magma to shoot upwards through narrow vents (pipes) at speeds of up to 250 kilometers per hour and be spewed out in a volcanic eruption.

As the magma rises, it unleashes fragments of foreign rock (xenoliths) and diamonds. Because this happens at great speed, not all these diamonds oxidize but are instead deposited around the edge of the pipe. Many of the volcanoes active today are situated on the boundaries of tectonic plates, where one plate slides underneath another (left). Under the increasing pressure, the water contained in the subducting plate heats up to such an extent that it melts the rock. The magma rises and forms a chamber that feeds a volcano.

At the boundary between the upper part of Earth’s mantle (olive green) to the mantle transition zone (light green and bluish) and from there to the lower mantle (dark red), the rock (mineralogy) changes – while the chemical composition stays the same – and thus its flow properties and density.

(Diagram not to scale)

From a depth of 200 kilometers

This is a key indication for the following generally accepted geoscientific theory: in the Phanerozoic, the eon from 540 million years ago to the present day, magma rose from a depth of over 200 kilometers during rare and explosive volcanic eruptions. These kimberlite eruptions broke open Earth’s solid and rigid upper layer – the lithosphere. The lithosphere is particularly thick in the continental nuclei and does not play a role in mantle convection, that is, circulation processes in Earth’s solid mantle. During these kimberlite eruptions, the magma propelled diamonds and other rock material out of Earth’s deep mantle – xenoliths – that formed there more than a billion years ago. “Nature has worked for us researchers and unearthed something that we would otherwise be unable to explore,” says Sonja Aulbach enthusiastically.

After the source of the xenoliths had formed in Earth’s mantle, it was altered by the processes taking place there. “During these processes, the respective mineral inclusions were in a perfectly inert container, the diamond,” says Sonja Aulbach. Comparing xenoliths and diamond inclusions thus delivers important clues as to how the lithosphere has evolved over hundreds of millions of years.

Obtaining a picture of early Earth from knowledge of the chemical composition and isotopic ratios of rock material calls for a basic understanding of how the chemical elements in the rock redistribute as it melts and crystallizes, as well as during pressure changes and transport processes. Laboratory experiments to study the behavior of substances at high pressure and different temperatures contribute to this understanding, and computer simulations help to reproduce the processes. “Here, we geoscientists approach early Earth from two directions: on the one hand, from the beginnings of the solar system, which meteorites tell us a lot about. And on the other hand, from today’s solid Earth, which consists of crust, mantle and core and in which many different types of rock have formed as a result of differentiation processes,” explains Aulbach. It is important to identify and retrace these processes, she says.

From magma ocean to the continents

Despite all scientific progress, our picture of Earth between its formation 4,567 billion years ago – an age calculated from meteorite finds – and the time around one billion years ago remains grainy. What is clear is that in the beginning Earth’s metallic core formed, which was surrounded by an ocean of liquid magma containing silicate. This was because Earth was much more energetic and thus hotter than it is today – the consequence, among other things, of high radioactivity and meteorite bombardment. Then, at least four billion years ago, gradual cooling caused a solid crust to form in places, even if viscous magma flows continued to predominate. This crust then partly melted again, while new crust crystallized in other places. In each of these processes, the chemical elements were redistributed: some remained in the mantle, while some, due to the size of their ions, among other things, accumulated in the liquid magma from which the crust formed.

The first rocks that have survived to the present day formed 4.02 billion years ago, and the first continental nuclei developed around 3.5 billion years ago. “Exactly when plate tectonics then began, that is, when lithospheric plates started to move on Earth’s mantle, is disputed,” says Aulbach. “In any case, our results indicate that there were plate tectonics three billion years ago and that parts of the early continental plates already rose above sea level at that time. This exposed them to weathering, with far-reaching consequences for material cycles and the development of life.”

Where at one time highly explosive eruptions transported diamonds from Earth’s depths to the upper regions of its crust, nowadays they are mined, such as here in Koidu-Sefadu in Sierra Leone, Africa. Photo: imageBROKER/Alamy

Connection between Earth’s mantle and the atmosphere

What happened to carbon over billions of years is also a key factor in the origin of life on Earth. Aulbach plans to concentrate more on this in the future. She has already proven that a kind of cycle already existed three billion years ago, in which carbon from the oceanic crust reached a depth of at least 150 kilometers. There, the carbon crystallized to form diamond, which then took part in the circulation processes taking place in the deep mantle, but is oxidized when it is slowly transported upwards as part of mantle convection. In this process, which continues to take place today, CO2 is produced, which is then ejected into the atmosphere when magma forms and through volcanism.

That is why geoscientist Sonja Aulbach sees diamonds through different eyes than most people, not only in terms of their monetary value. Her reply to the famous advertising slogan “A diamond is forever” of the De Beers jewelry company is: “According to the current state of knowledge, we could by all means argue that the carbon dioxide emitted by some volcanoes today originates from combusted diamonds.”

About

Sonja Aulbach studied geology and mineralogy at Goethe University Frankfurt and earned her doctoral degree at Macquarie University in Australia in 2005. After stays as a postdoctoral researcher in the USA and Canada, she returned to Goethe University Frankfurt in 2009, where she has since been conducting research in the Department of Geosciences. She has been a Heisenberg Fellow since 2022 with the project “Crust-Mantle Evolution and Volatile Cycles of Earth’s Interior Through Time”.

The author

Frank Frick holds a doctoral degree in chemistry and has worked as a freelance science journalist for about 25 years. He writes for journals, research institutions and corporate research departments. He lives in Bornheim near Bonn.