For the great Romantic author, reality had many dimensions

E.T.A. Hoffmann is considered one of the most influential German authors, at the international level, too. With his tales, in which the worlds of dream, fantasy and insanity exist on a par with reality, he is a forerunner of many later writers and genres. A discussion with Professor Wolfgang Bunzel, Hoffmann expert and head of the Romanticism Research Department at the Freies Deutsches Hochstift in Frankfurt, one of Germany’s oldest cultural institutes.

Sauter: E.T.A. Hoffmann never visited Frankfurt on Main, but his literary fairy tale “Master Flea” is set in the city. Therefore, what made Hoffmann choose Frankfurt?

Bunzel: To be honest, Hoffmann scholars were mostly at a loss on this point for a long time. They merely saw a connection to Friedrich Wilmans, the Frankfurt publisher, and argued that Hoffmann wanted to accommodate him by setting the tale in Frankfurt. But that was solely due to the lack of a better explanation.

Urban reality is only one dimension in Hoffmann’s work, which always also opens the door to the fantastic, into the worlds of dream, intoxication and insanity. Perhaps it was insignificant where reality was?

That would be the wrong conclusion. If you look at all of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s works, it becomes clear that he often chose large and well-known cities for the setting. “Ritter Gluck” and “A New Year’s Eve Adventure” are set in Berlin. “The Golden Pot” in Dresden, “Princess Brambilla” in Rome and “Master Flea” in Frankfurt am Main. To a certain extent, this is a narrative principle in Hoffmann’s work. He chooses these cities because, on the one hand, they are places where social life is densely compacted. On the other hand, he wants to anchor events in a local setting, which – as you rightly say – always quickly drift off into the fantastic. For this he needs a fixed topography.

By setting the events in a reality that is as concrete as possible, he achieves more credibility for the fantastic dimension of his texts?

Yes, he endeavours to give this somewhat “dangerous” component – that is, fantasy – a credible foundation, to relate it back to reality. In doing so, he is reacting to the accusation that everything is just fabrication, mere imaginings. Hoffmann claims that reality is permeable to the fabulous, you just have to look closely enough. His texts are very precise arrangements, and, if you look closely, doors to the fantastic and the fabulous open in reality, which we believe to be so permanent and unshakeable.

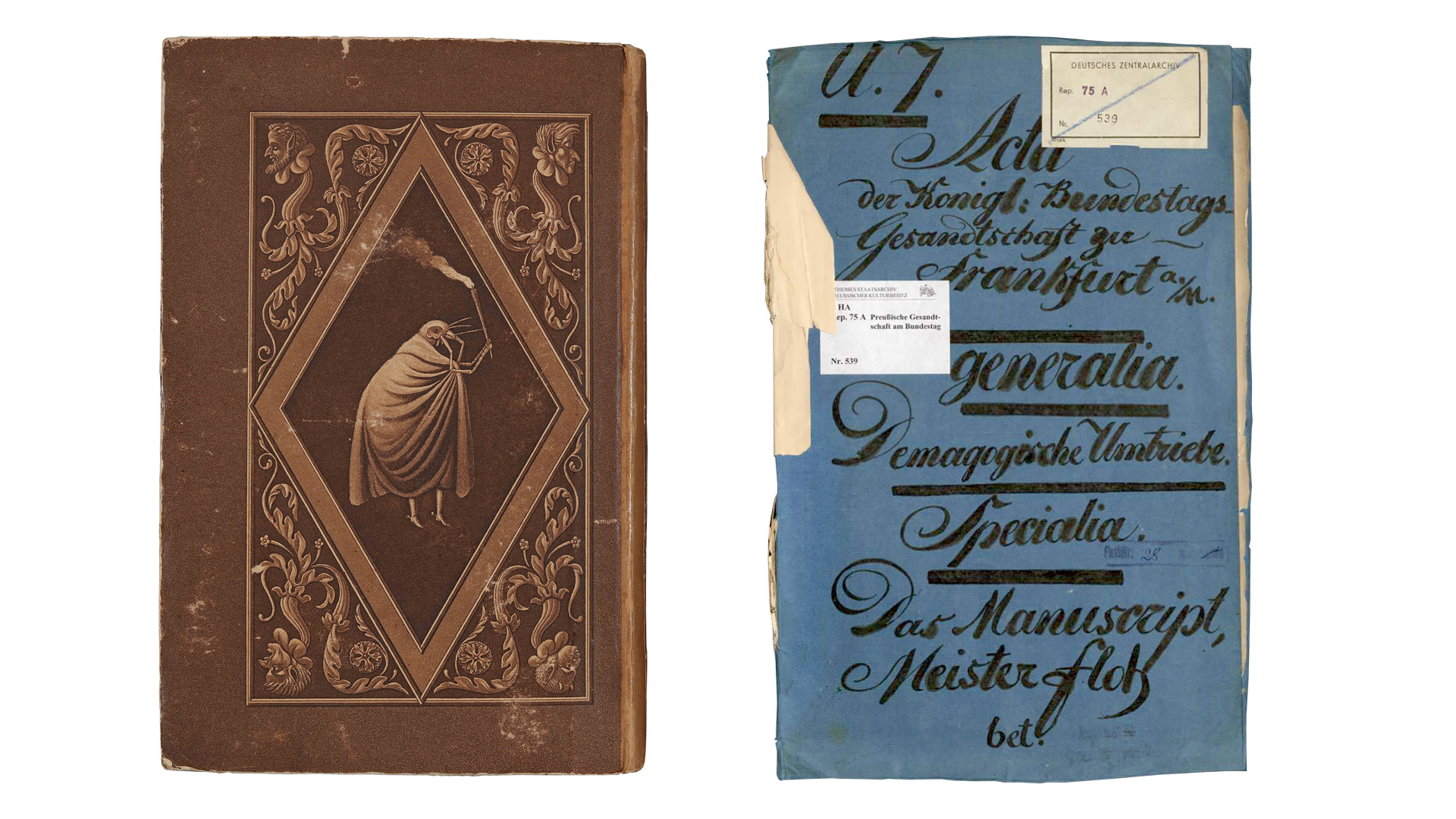

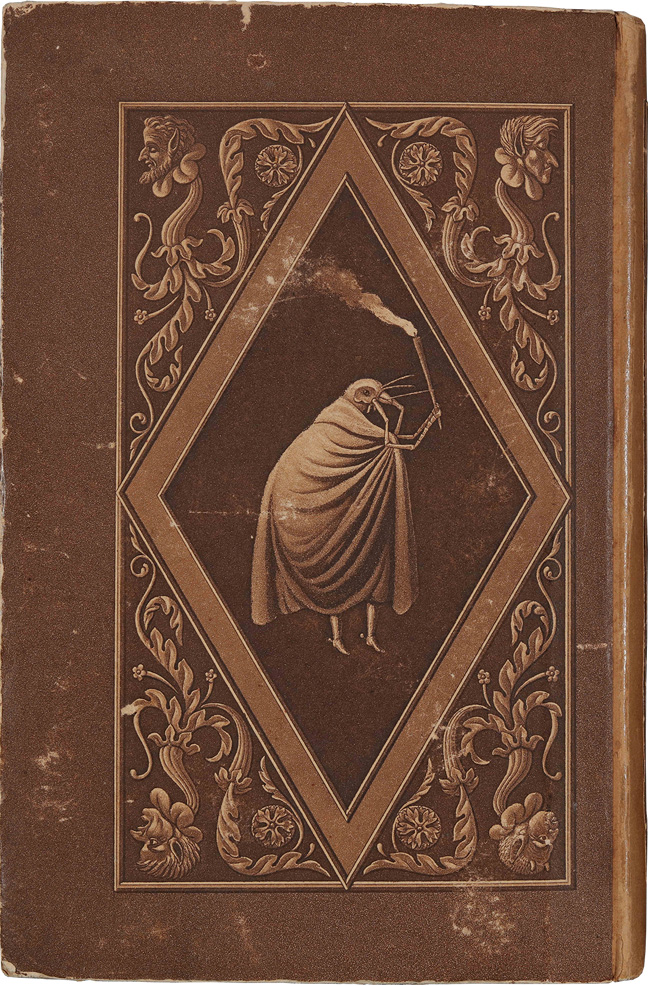

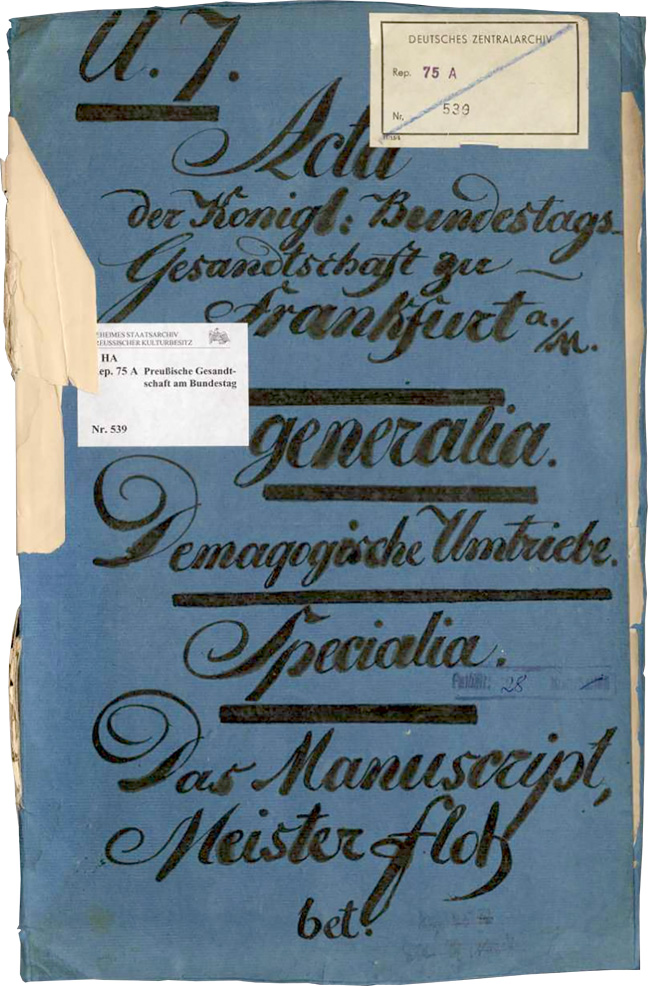

Hoffmann’s fairy tale novel Master Flea is set in Frankfurt am Main. He chose the motif for the cover himself; it originates from a natural history book.

“Master Flea” triggered quite a political stir; the corresponding documents have survived.

Illustration: „Master Flea“; Manuscript: Prussian Secret State Archives; Book cover: Bamberg State Library

Does this mean that the settings are interchangeable, the main thing is that they are familiar and can be accurately described?

No, it is not that. E.T.A. Hoffmann makes very conscious use of certain ideas associated with a city, known as imagines. Rome, for example, is a southern city that stands for historical depth, but also for joie de vivre. As the time for the plot of “Princess Brambilla” he chooses the Roman carnival, where everything takes place in the streets, the city becomes a huge stage. Such constellations can only be found in one particular place, they do not work elsewhere.

And why is Frankfurt the ideal setting for “Master Flea”?

Frankfurt has always been regarded as a city of commerce and business, of the trade fair, of the marketplace. Peregrinus Tyß, the main character in “Master Flea”, has a very pragmatic father, a successful and wealthy merchant who also speculates on the stock exchange. He wants his son to pursue the same calling one day. Hoffmann uses Frankfurt’s urban imago of a merchant city centred on trade and the stock exchange. But Peregrinus Tyß, the childlike, dreamy and, as it seems, developmentally retarded young man, personifies a countersphere. He indeed grows up in Frankfurt, but he refuses to follow in his father’s footsteps. And it is here that Hoffmann makes use of another of Frankfurt’s particularities, its hidden side as a city steeped in culture. Goethe, for one, is representative of this, which is why there are various allusions to him in “Master Flea”. But the Brentanos, one of the wealthiest merchant families in Frankfurt, also lived here. Only the children Clemens and Bettine did not want to be like their father and older siblings and instead became protagonists of Romanticism. These two faces make the City of Frankfurt the ideal setting for “Master Flea”.

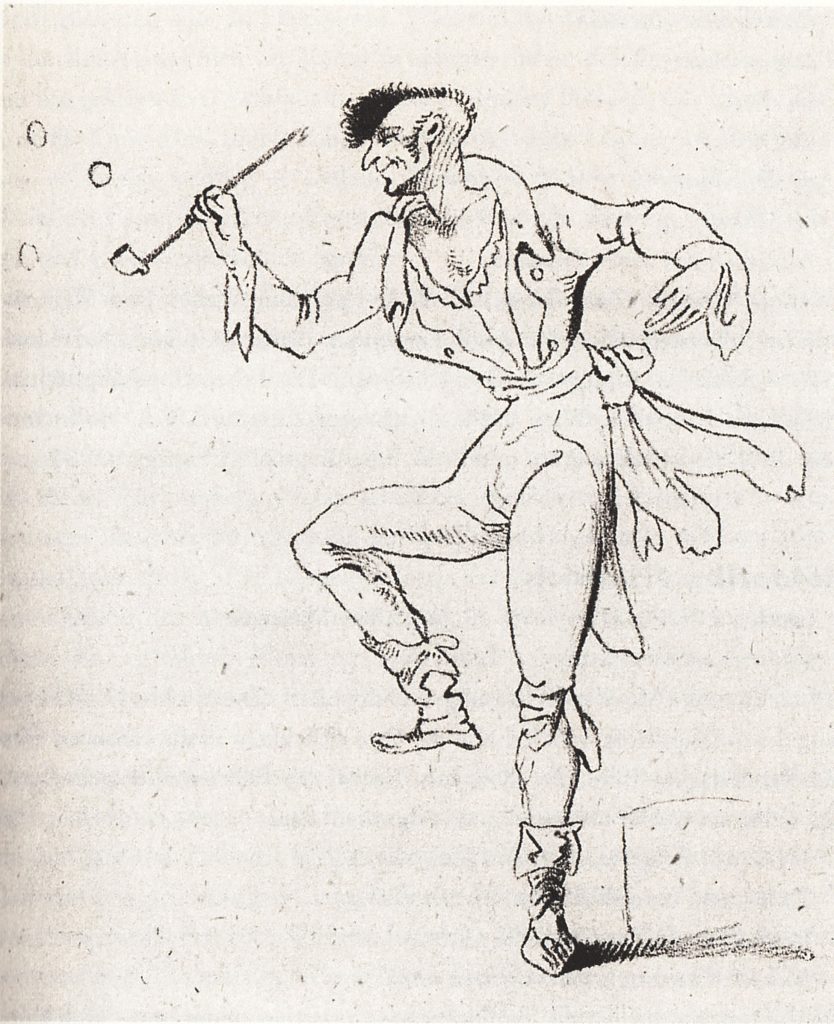

Hoffmann had many talents and frequently added a self-portrait to his letters, such as the drawing at the end of this letter to his friend Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel.

In this story, a flea is responsible for opening the door to the fantastic. What role does the fantastic play in this work?

Fantasy is already reflected in the subtitle: “A Fairy-Tale in Seven Adventures of Two Friends”. We should take special note of this. The story of a friendship is told in seven adventures, the seven main chapters, and it is rather bold. Why? Because it is about a cross-species friendship between a human and a flea. That people and their pets form a close symbiosis is nothing unusual. But fleas? We regard them as annoying and harmful insects, and we can conclude from the difference in size alone that communication is impossible.

“The Nutcracker and the Mouse King”: in his Christmas fairy tale, Hoffmann has mice and toy soldiers line up against each other.

Illustration: Freies Deutsches Hochstift

But then there is communication after all because the flea can speak, like the animals in Aesop’s Fables.

Yes, Hoffmann uses this device very consistently and illustrates a dimension that humans overlook. As it turns out, Master Flea is not just any flea, but the king of the whole flea population. And this flea population is so intelligent that it has invented things that humans are not yet even aware of. For example, the fleas have designed an optical masterpiece that can be used to read minds!

Everyone would like one of those sometimes!

Hoffmann is simply unbeatable here in that he really does put such ideas consistently into practice which are in fact obvious and says: Why shouldn’t that exist, a microscopic lens for reading thoughts capable of being inserted into the eye like a contact lens? In a similar way, these two completely different beings enter into a close and friendly relationship with each other. And the reader learns that the flea kingdom is also politically advanced: although there is a king, the flea population is essentially organised as a republican state.

Quiet criticism of the political situation at the time?

Yes, a more than charming comparison. In 1815, Frederick William III, the Prussian King, made a constitutional promise that he never kept. E.T.A. Hoffmann, as an astute writer and civil servant, contributed another dimension to this story: from both a socio-political as well as a scientific perspective, the fleas emerge not as a primitive species, but instead as superior to humans.

Does Hoffmann resort to fantasy here because he was unable to say certain things forthrightly?

Animal figures can, of course, be used to articulate things that could not be said without further ado or even at all under the conditions in the public realm at that time – meaning that censorship existed. But E.T.A. Hoffmann goes even further, the animal is not only a vehicle for the author. He also wants to say: Dear humans, forget your conceited ego: you are not the pride of creation nor superior to all other living beings. You should not command over other creatures or disdain them.

Illustration: Freies Deutsches Hochstif

E.T.A. Hoffmann as a forebear of animal ethics?

Absolutely, he was surprisingly modern here, too. Of course, he does not use the term “animal ethics”, but in fact that is precisely what it is about: rethinking the relationship between humans and animals. Many of his tales have animals as protagonists, the dog Berganza, the tomcat Murr or, as just mentioned, Master Flea. In this very ingenious story, the insect, the pest, the disgusting creature, which until then had been completely disparaged, is ennobled in a way that we have not experienced before.

Tomcat Murr is introduced as a rather pompous narrator and is not entirely likeable.

It is parody and persiflage on many levels. “Tomcat Murr” parodies the Bildungsroman and the self-assured autobiography. Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship” and “From my Life: Poetry and Truth” were the model for both. It is a tongue-in-cheek confrontation with Goethe. Hoffmann does not want to denounce Goethe, but instead to show the weaknesses of these genres in an unexpected, witty and alienated way. And he definitely likes the tomcat, who is modelled on his own cat called Murr.

Illustration: Bamberg State Library

Why, in fact, did E.T.A. Hoffmann not content himself with describing reality?

Because reality is constrained, unfinished and thus in need of improvement in every respect. For him, reality is an unsatisfying situation. Why write about it yet again? Fantasy and fiction are an opportunity to create counterworlds. This is what mostly motivates Hoffmann, and a utopian element can, of course, be detected in his work. Above all, Hoffmann shows here that he is a representative of Romanticism: the poetisation of reality and of life should lead to a more perfect state. The productive power of the imagination makes this conceivable.

Is this also the reason why literature and other media have picked up Hoffmann’s tales so often? Because they leave so much room for the reader’s imagination?

The criterion of literary fantasy is that how things really are ultimately remains undecided. Is that which is being narrated fantasy, a feverish dream or a delusion? This creates a constant tension because readers are challenged again and again to solve the mystery – and yet fail to do so. The fascination associated with this has survived. That is why this form of representation is still used so much today by the various arts and by media formats.

Another way out of reality is insanity. This manifests itself above all in the bandmaster Johannes Kreisler, in whom genius and insanity are close together. Does this character contain any of Hoffmann’s autobiographical traits?

Kreisler is something like E.T.A. Hoffmann’s alter ego and appears in several of his works. Hoffmann is not interested in processing traumas in accordance with psychoanalytical teachings, but instead uses this artificial figure, which is close enough to him but not identical with him, to act out many of the things that concern him.

Insanity here is more of a state of being and not necessarily pathological?

We tend to attach the label “pathological” to insanity from the very start, but E.T.A. Hoffmann does not. With him, insanity remains ambiguous: like intoxication and dream, insanity is productive because it unclogs our perception and allows us to establish connections between things that we would otherwise not associate with each other at all. But insanity can also be compulsive and hold the risk of misjudging reality, then it becomes a problem. But these exceptional states – insanity, intoxication, dream, the unbridled power of the imagination – are per se productive. The person who gets along in life without insanity and without intoxication is the Philistine, the great adversary of Romanticism.

Could we say that E.T.A. Hoffmann has, to a certain extent, laid bare many aspects of human nature?

It is not without reason that Romanticism is regarded as the discoverer of the unconscious, the sphere beyond rationality, beyond the intellect, where things are at best connected with each other by association. E.T.A. Hoffmann follows precisely this path, sounds out the unconscious, the unknown in the human mind, and in so doing also stirs up many things that can trigger fear. He describes these phenomena in a fascinating way and proceeds to the point where the whole thing tips over into fixations, into delusions, and then becomes problematic. In the story “The Sandman”, for example, the main character Nathanael clearly imagines things and, in his delusion, he creates a self-constructed reality for himself; Nathanael becomes a prisoner of his own imagination.

In “The Sandmann”, Nathanael falls madly in love with the “automaton” Olimpia, a mechanical doll and barely differentiated character who only ever says “Ah!”. Today, we have ChatGPT and robot vacuum cleaners, and in Maria Schrader’s “I’m Your Man” a young woman and an android interact as equals. What continues to fascinate us about “The Sandman”?

“The Sandman” is a tale with many layers that makes us aware of how easily we are taken in by our own delusions. E.T.A. Hoffmann makes it clear to the reader from the outset that Olimpia is a mechanical human. The perfectly brought-up young woman with the most impeccable manners and such amazing charisma is a projected phenomenon. But Nathanael is so blinded by love that he overlooks the merits of Clara, who is human and, of course, not as perfect as Olimpia in many ways, but much more authentic than this artificial being. Hoffmann shows how quickly a vivid imagination, when exaggerated, leads to obsessions, loss of reality and false perceptions.

That people become fixated is something that happens in our times, too.

Yes, a few years ago we would not have thought it possible that conspiracy theories would become socially acceptable, that even intelligent people would seriously discuss them and block any counterargument. They consider objections to be proof that the other person is deluded, which brings any discussion to a grinding halt. This leads to a totally hermetic self-image, a self-created world of imagination where they consciously cage themselves in.

And “The Sandman” makes us think about this?

Of course, Hoffmann’s works are historical texts that do not suddenly become contemporary in a naïve way. But it is interesting that certain problems were recognised and portrayed a long time ago. This allows us to recognise present-day issues more accurately and to better understand the functioning of certain mechanisms, for which we otherwise lack the distance. We can read cleverly formulated essays and treatises about neuroses, obsessions and conspiracy theories, but through literature we experience such phenomena much more vividly and thus more immediately.

Interview: Anke Sauter

Spotlight on Romanticism

A new research focus in cultural studies at Goethe University Frankfurt

“Romantic ideas and ways of thinking, the aesthetic notions of Romanticism – much of it continues to make an impact today,” says Frederike Middelhoff. As a literary scholar, she is herself looking at the relationship between Romanticism and migration in a project funded by the Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften, a centre for the promotion of research in the humanities and social sciences. Because, similarly to today, many people sallied forth before and during the 18th century and had to leave their home countries behind – for example in conjunction with the French Revolution. This was also reflected in the literary texts of the time. Modes of self-reflection, modern individualism, the observation of psychic phenomena, alternative forms of coexistence – these topics also have their origins in the intellectual and cultural history of Romanticism. And nowhere near all the most important texts are already generally known; interesting discoveries also lie in wait outside the canon. For example, the many texts and creative practices of female authors who have slipped “under the radar” for a long time even in research and deserve a larger audience. Since 2021, a series of workshops entitled “Kalathiskos – Women Writers of the Romantic Period”, which Middelhoff is organising together with private lecturer Dr Martina Wernli at Goethe University Frankfurt and which is already entering the fourth round in 2023, has been dedicated to them.

Frederike Middelhoff, born in 1987, has been Professor of Modern German Literature and Romanticism Studies at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2020. Designating her professorship to this field of research was an important decision for the university – and for Romanticism Studies in Germany: no other literary studies professorship in the country is dedicated explicitly to Romanticism. A clear signal for Frankfurt as a place for Romanticism Studies. The city played its own part in Romanticism – not least as the home of Clemens and Bettina Brentano and Karoline von Günderrode.

However, Romanticism research in Frankfurt is also strongly connected to the university’s close collaboration with the Freies Deutsches Hochstift. This organisation, one of Germany’s oldest cultural institutes, is the body responsible not only for the Goethe House in Frankfurt but also for the German Romanticism Museum, which opened in 2021, and – together with the town of Oestrich-Winkel – for the Brentano House. There have been links between staff at the Freies Deutsches Hochstift and the university for many years: Professor Anne Bohnenkamp-Renken, who has headed the former since 2003 and was awarded the Hessian Culture Prize in 2023, has been an honorary professor at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2004 and a full professor there since 2010. Professor Wolfgang Bunzel, head of the Romanticism Research Department at the Hochstift, is also an honorary professor at Goethe University Frankfurt. Romanticism research was given a further boost through the appointment of the literary scholar Professor Roland Borgards in 2018, who not only deals with the Romantic period in his research work on animals in literature.

In 2021, the scientific network “Current Perspectives in Romanticism Studies” of the German Research Foundation also began work and will continue to receive funding from the German Research Council until 2024. Here, young researchers are coming together to discuss tried and tested approaches to Romanticism Studies and to further develop their own research projects in exchange with internationally renowned Romanticism scholars. The network is producing a collected volume that aims to provide an overview of recent Romanticism research. In addition, a virtual database with texts on European Romanticism is being compiled, as well as a digital research biography.

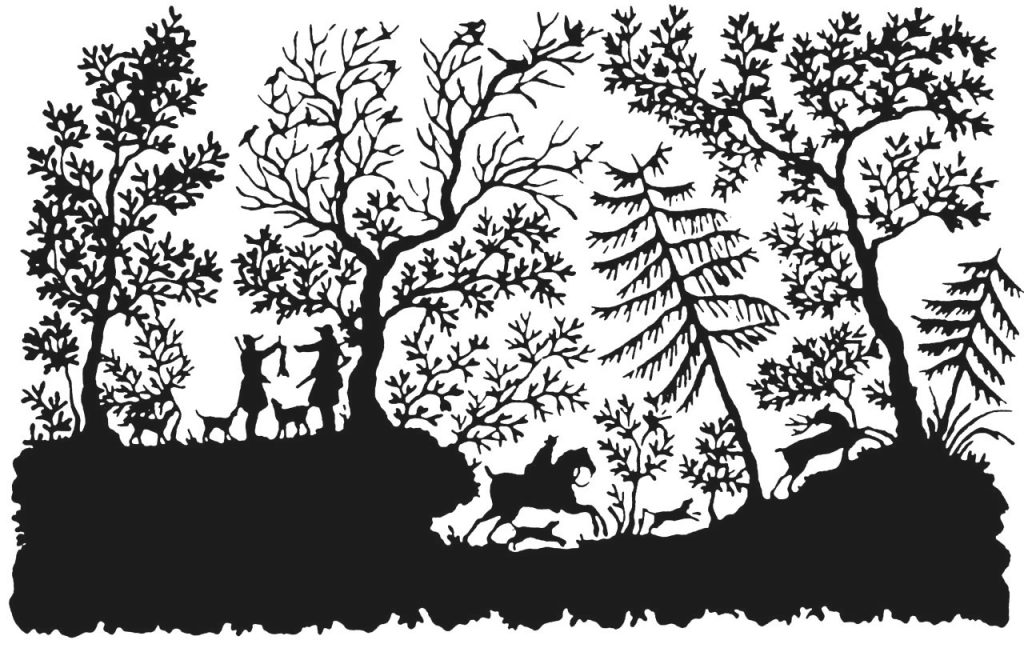

aesthetic embodiment of nature. Seen here is the papercutting “Hunting Scene” by Bettina Brentano.

Illustration from: Klaus Günzel: Die deutschen Romantiker. Artemis, Zurich 1995

Ecological thinking also gained momentum during the Romantic period, which, among other things, reacted critically to industrialisation in Europe – and focused instead on the other-than-human dimension of culture and the human impact on ‘nature’. The initiative “Romantic Ecologies”, a project of the Rhine-Main Universities (RMU) run by Professor Roland Borgards and Professor Frederike Middelhoff together with the literary scholar Professor Barbara Thums from Mainz, is devoted to questions in this area. In addition, 2022 saw the launch of a series entitled “Neue Romantikforschung” (New Romanticism Research), published by J.B. Metzler-Verlag and edited by the Romanticism researchers in Frankfurt. A prize for outstanding research in the field of Romanticism has also been launched: this year, the Klaus Heyne Award for German Romanticism Research will be conferred for the second time. The science prize, which the paediatrician and Romanticism expert Professor Klaus Heyne (1937-2017) from Kiel donated to Goethe University Frankfurt for research on German Romanticism, is worth €15,000.

Frederike Middelhoff notices from her courses there is great interest in the Romantic period among young people, too: “Seminars and lectures dedicated to Romanticism – for example ‘Romantic Ecologies’, ‘Multilingualism in Romanticism’ or the ‘Hoffmannesque Visitations’ of E.T.A. Hoffmann in the lecture of the same name in the 2022/23 winter semester – are extraordinarily in demand,” she says happily. Further evidence that Romanticism has a lot to say about current topics as well.

You can find an overview of Romanticism research at Goethe University Frankfurt under: https://romantikforschung.uni-frankfurt.de

Contact

Frederike Middelhoff (middelhoff@em.uni-frankfurt.de)

About

Wolfgang Bunzel, born in 1960, is director of the Romanticism Research Department at the Freies Deutsches Hochstift in Frankfurt am Main. He has held an adjunct professorship in Modern German Literary Studies at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2013. He is one of the curators of the memorial exhibition “Fantastically Uncanny – E.T.A. Hoffmann 2022”, which was shown in Bamberg, Berlin and Frankfurt am Main.

wbunzel@freies-deutsches-hochstift.de