How gold, lead and heavy metals were formed

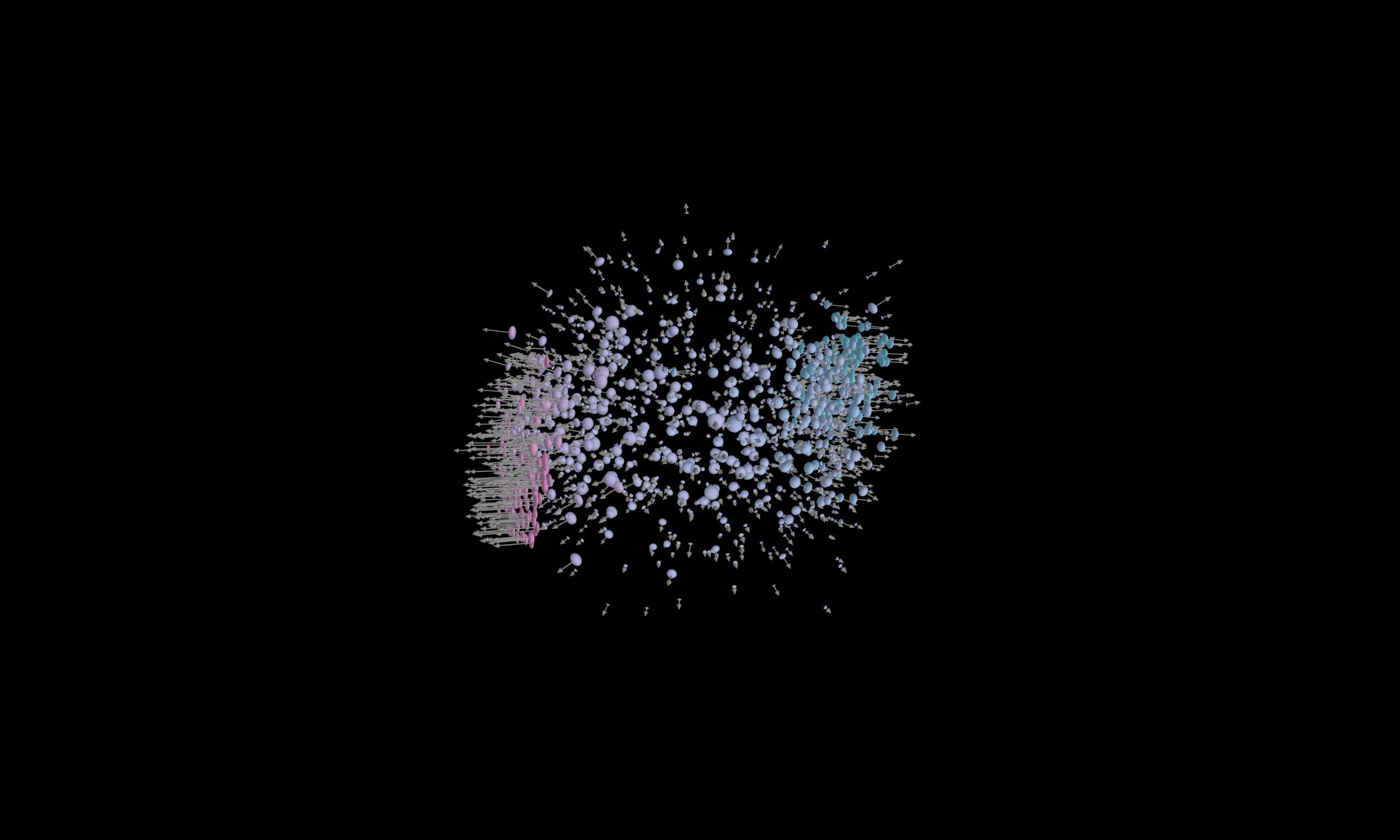

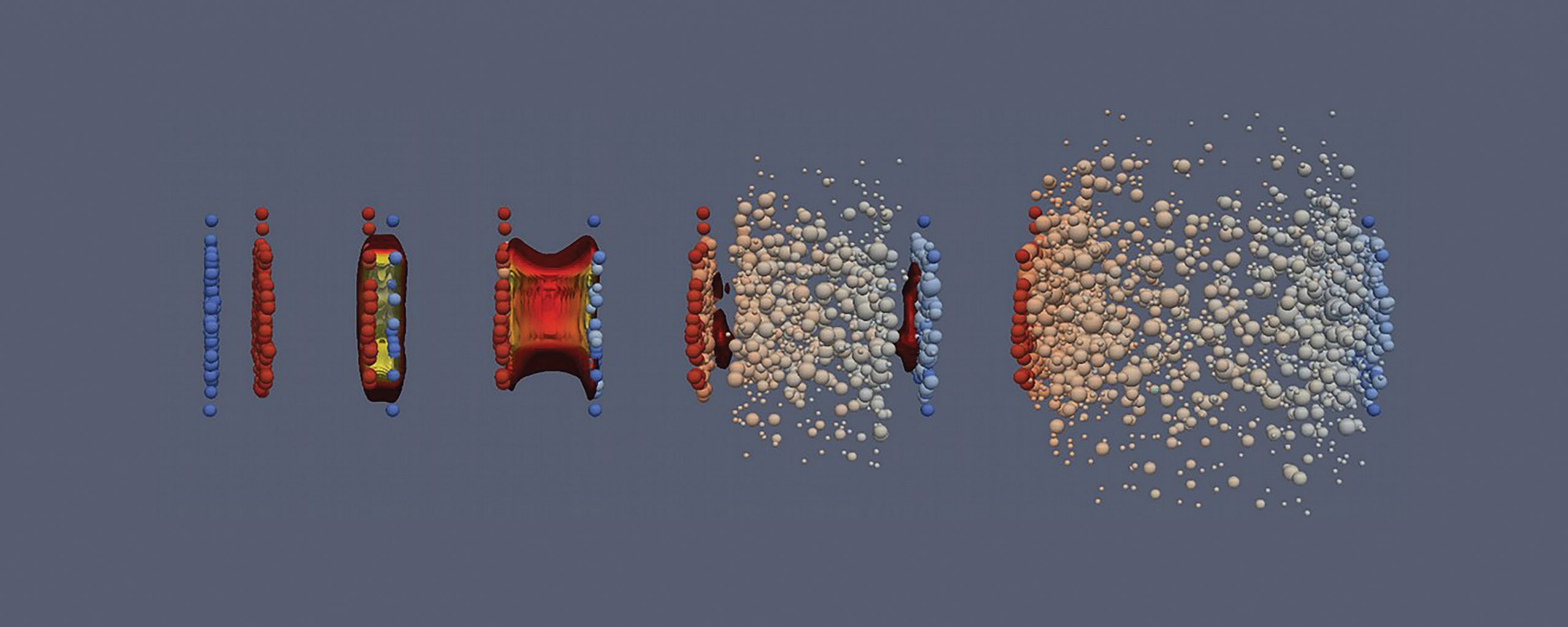

When the nuclei of heavy atoms collide at almost the speed of light, countless new particles form from the tremendous energy released during the collision, as this simulation shows. These particles reveal the properties of the extremely compressed matter at the time of the collision. Photo: Hannah Elfner

In the ELEMENTS cluster project, Goethe University Frankfurt, TU Darmstadt, Giessen University and GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research are conducting theoretical and experimental research in order to understand the structure of matter under extreme conditions. Such research shows, for example, how collisions of neutron stars led to the formation of many of the heavy elements on our planet

Studying the origin of heavy elements is an adventure into the realm of superlatives. Only the lightest elements, such as hydrogen and helium, emerged from the Big Bang. To create all the matter that makes up planets like Earth and that we ourselves are made of, these light atomic nuclei had to gradually combine into heavier elements. The heavier the elements, the more extreme conditions they needed to form: Who would have thought when looking at the gold ring on their finger that this metal stemmed from a celestial collision between neuron stars? In the ELEMENTS cluster project, scientists want to investigate matter under precisely such extreme conditions. Through their experiments with particle accelerators and by comparing their results with cosmic data, they want to track down the origin of the elements and learn about their behavior in cataclysmic cosmic processes – processes that involve sudden destruction (from the Greek kataklysmos).

How elements formed in the course of cosmic development is called nucleosynthesis. This process involved many steps – from nuclear fusion inside stars, such as our Sun, to supernova explosions and neutron star collisions. The first steps in this process, the nuclear fusion of hydrogen to helium and then to carbon, oxygen, iron and other moderately heavy elements, is already well understood today. These elements are essentially formed by fusion processes in stars, where light stars can only produce light elements, whereas heavy stars can also bake together heavier elements up to the size of iron and nickel.

How heavy elements form

But how heavy elements such as gold, lead and uranium form raises many questions: What conditions must prevail so that heavy atomic nuclei can continue to fuse together? “Sooner or later, fusion reaches its limits,” says Hannah Elfner, who is professor of theoretical nuclear physics at Goethe University Frankfurt and works at GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt as well as in the ELEMENTS cluster project. “The heavier an atomic nucleus is, the greater its electrical charge. Since atomic nuclei are incredibly small, very strong electric fields must prevail near the atomic nucleus that repel other atomic nuclei.” Even the high temperatures in the center of stars are not enough to melt such heavy atomic nuclei. On Earth, the high temperatures required for operating fusion reactors such as ITER also represent a hurdle, although only hydrogen is to be fused there.

“Very heavy elements do not form through nuclear fusion but by the accretion of neutrons, which are electrically neutral and therefore not repelled by the atomic nuclei,” says Elfner. But free-flying neutrons are instable, they decay if they are not captured by atomic nuclei. Producing heavy atomic nuclei takes a lot of neutrons. “Such a large number of neutrons is only released during extreme cosmic processes,” explains Elfner. These are, first of all, supernova explosions in which entire stars are destroyed. Depending on the type of supernova, a black hole, a neutron star, or nothing more than a hot cloud of expanding gas can be left behind. When neutron stars collide, this creates even more extreme conditions than a supernova. The heaviest elements form during such gigantic explosions, which can even shake up space and time to such a degree that gravitational wave detectors can spot these collisions. The first recording of this kind was achieved a few years ago and awarded a Nobel Prize.

“Neutron stars are particularly exciting for astrophysicists and nuclear physicists because they are the densest objects in the Universe, and to date we do not know what is at their center, where the density is highest,” says Tetyana Galatyuk, who is also involved in the ELEMENTS project and professor of experimental particle physics at TU Darmstadt. “In our experiments we focus less on the gravitational waves triggered when such objects collide. Rather, we are rather looking at the composition of nuclear or new forms of matter under these extreme conditions.”

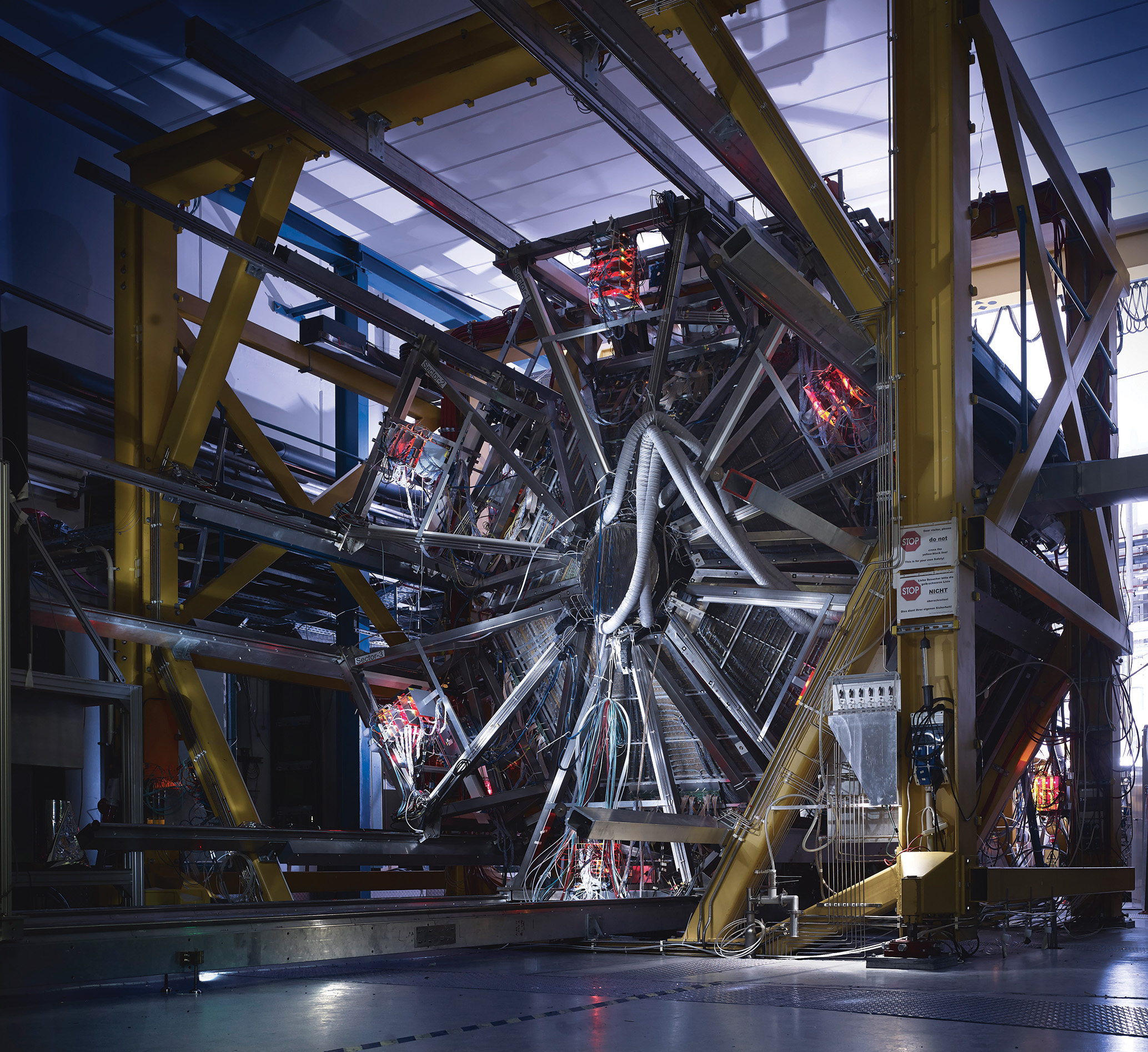

Researchers from nine countries contributed to the construction of the HADES detector at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research, which can be seen here from the back. The detector elements are arranged in sections like an umbrella and catch the particle showers generated by the collision of heavy atomic nuclei. Foto: Jan Hosan für GSI/FAIR

When atomic nuclei burst

This is because the atomic nuclei themselves are already subjected to enormous forces. An atomic nucleus is tiny compared to its electron shell – smaller by a factor of 100,000. Neutrons and positively charged protons crowd together in this extremely small space. “In ELEMENTS, we want to see what happens if we further compress and heat up this nuclear material,” explains Galatyuk. “To do this, we fire heavy atomic nuclei at each other in particle accelerators such as here at GSI or at CERN and Brookhaven in the US and analyze the collisions.” Large detectors reveal the traces that these nuclear collisions leave behind.

Within a very short time, processes take place that are highly complex and require intensive analysis. “Such events can longer be calculated simply by applying the known laws of nature,” says Elfner. The atomic nuclei burst, mix and can even assume new states of matter. “To interpret the data from such experiments, we theorists need to work with models and simulations.”

Without close collaboration between experimental and theoretical research, all this would be impossible: only by means of complex analyses can scientists identify interesting events among the many traces in the detectors that deliver new insights into nuclear matter. “If we fire heavy atomic nuclei such as lead or gold nuclei at each other, a new state of matter can form there, known as quark-gluon plasma,” explains Galatyuk. In this process, the protons and neutrons in the atomic nuclei burst open and their elementary particles, the quarks and gluons, fly freely for a fleeting moment before they reunite to form nuclear particles.

New York as a sugar cube

“Such collisions reach temperatures of around a trillion degrees, which is 100,000 times hotter than in the center of our Sun,” says Galatyuk. “In the process, the already extremely dense nuclear matter is squeezed again by a factor of three to five and reaches a gigantic density of more than 280 million tons per cubic centimeter. It’s like compressing the entire city of New York with all its buildings down to the size of a sugar cube.”

However, the ultra-hot fireball produced when heavy atomic nuclei collide exists only for an extremely short time. After less than a tenth of a zeptosecond (10-22 seconds or 0,000 000 000 000 000 000 000 1 seconds, it collapses again. “Within this short period, the numerous quarks and gluons in this fireball collide about a dozen times, which makes for a very complex signal in the detector,” explains Elfner.

However, the researchers benefit from a welcome effect here: in rare cases, a very high-energy light particle is generated in the middle of a hot fireball, which then converts its energy into an electron and positron pair – the electron’s antiparticle. The electron and the positron do not interact with the quarks and gluons in the fireball and can therefore carry information about its interior to the outside.

Collision of heavy nuclei: near the speed of light, the atomic nuclei are no longer spherical but elongated (blue and red, left). When they collide, a fireball forms, in which quark-gluon plasma, a “soup” of elementary particles, is produced for a tiny fraction of a second. When the fireball expands, the quarks and gluons combine again to form nucleic building blocks, known as hadrons (right). Photo: Hannah Elfner, Jonah Bernhard, MADAI collaboration

The fireball in HADES

“We can use these electron-positron pairs to take ‘X-ray images’ of the fireball because they can easily penetrate it, similarly to how X-rays pass through the human body,” says Galatyuk. “An important part of my work is therefore to develop methods and detector components for recognizing and evaluating these electron-positron pairs.”

At the moment, the nuclear physicist is still using the HADES detector (High Acceptance Di-Electron Spectrometer), which has been in operation at GSI since 2002. At the new FAIR accelerator center, which is currently being built in Darmstadt, the CBM detector (Compressed Baryonic Matter) will continue this task. “So far, for example, we have accelerated gold nuclei to 90 percent of the speed of light, but FAIR can achieve up to 99 percent of the speed of light,” says Galatyuk.

This is just one side of the coin: far more collisions will be possible at the new facility. This also means that the new detector will have to record data about 500 times faster than the old one. Experiments that would previously have taken a month could now be carried out during the lunch break. This opens up a vast number of possibilities, and it will hopefully be possible to corroborate especially rare effects more quickly and with convincing evidence. “But the greater number of collisions also means that the signals from the electronic components must also be read and saved much faster,” explains Galatyuk. “We will set new records worldwide in this area.”

IN A NUTSHELL

- Particle accelerators can bring charged atomic nuclei (ions) to almost the speed of light.

- If these ions collide with atomic nuclei, the atomic nuclei break down into their elementary particles for fractions of a second and in the smallest space.

- With such experiments and theoretical calculations, researchers want to find out how solid and plasma phases fuse in nuclear matter.

From atoms to stars

The Darmstadt researchers have even tested some of the detector components on the Brookhaven accelerator. After traveling by container across the Atlantic, the new components have done a good job at the US facility and might even remain there at the Americans’ request while scientists at GSI work on further developments.

Once the system is up and running as intended, it should be capable of fulfilling even the more unusual requests of the scientific community. “We would like to know whether nuclear matter undergoes the same phase transitions that we know from water,” says Elfner. During the transition from ice to water or from water to steam, the temperature remains constant while energy is supplied. This additional energy changes the aggregate state. “It is assumed that this is similar for nuclear material,” says Elfner. To verify this, the scientists need new data such as the electron-positron X-ray images from the heart of the little fireballs. But not only that. Producing exotic particles and investigating known phenomena with greater precision are also on the research agenda.

“In our work, it is always fascinating to see how the physics of the smallest particles, subatomic nuclear and particle physics, is connected with cosmic phenomena such as neutron stars, supernovae and nucleosynthesis,” says Elfner, summing up. “And without very close collaboration between everyone involved in theoretical and experimental research, none of this would be possible.”

About

Hannah Elfner, who was born in Frankfurt in 1982, is head of the “Hot and Dense Quantum Chromodynamic Matter” department at GSI and responsible for coordinating theoretical research there. She studied physics at Goethe University Frankfurt, where she also earned her doctoral degree. She then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Helmholtz International Centre for FAIR, before becoming a Feodor Lynen fellow at Duke University in North Carolina. She then returned to Germany and took on a professorship at Goethe University Frankfurt and management positions at GSI. Having been a fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies since 2013, she has been a senior fellow there since 2022.

Tetyana Galatyuk, born in Kuznetsovsk, Ukraine, in 1981, is head of the “QCD Matter Research” group at GSI and Professor of Experimental Hadron and Nuclear Physics at the Institute for Nuclear Physics at TU Darmstadt. She holds a Master’s degree in nuclear and particle physics from the University of Kiev and a doctoral degree from Goethe University Frankfurt. Among other awards, she has received the Röntgen Prize of Giessen University and the Prize of the Association of Friends and Benefactors of Goethe University Frankfurt. She is spokesperson for the alliance “Cosmic Matter in the Laboratory” within the Helmholtz program “Matter and Universe” and chairperson of the Committee for Hadron and Nuclear Physics in Germany.

The author

Dirk Eidemüller, born in 1975, studied physics (major) and philosophy (minor) in Darmstadt, Heidelberg, Rome and Berlin. He graduated in astroparticle physics and holds a doctoral degree in philosophy of science. He lives in Berlin and works as a freelance author and science journalist.