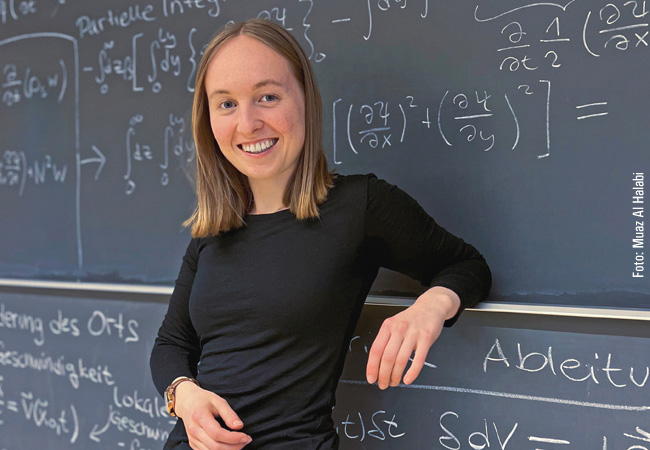

Lawyer Samira Akbarian’s thesis on the highly topical subject of “civil disobedience” won her the 2023 Werner Pünder Prize.

UniReport: Dr. Akbarian, your thesis bears the title “Civil disobedience as an interpretation of the constitution”. That almost sounds like a comment on the current discussion about the protests by climate activists. How did you come up with this topic?

Dr. Samira Akbarian: After my first state examination, I went straight into the second; I was very much focused on actual practice. While studying law, I also completed a Bachelor’s degree in sociology and political science. I was mostly interested in political theory, and democratic theory in particular. Following my legal clerkship, I wanted to return to academia and write about this topic. The term “post democracy” has given rise to a feeling – both scientifically discussed and proven – that it is anything but easy to be politically active nowadays: Economic maxims dominate many political processes, and the discourse at times seems “expertocratic”, i.e. dominated by experts. This gives rise to a general feeling of political powerlessness. I asked myself what legal starting points exist for investigating this subject. During my research, I came across Hannah Arendt’s essay on “Civil Disobedience.” Principally speaking, disobedience is a form of protest that enables direct democratic influence, and is therefore potentially also directed against a feeling of powerlessness. At that time – we are talking about 2017 – there had been very little legal research conducted on this topic. Things have definitely changed since.

So your work is interdisciplinary and supplements legal questions with aspects from the social and political sciences.

Yes, my work integrates many aspects from political theory, links them with constitutional theory, and applies them to legal cases. Conversely, it is of course also useful to look at radical democratic theories from a constitutional perspective.

Many people are concerned about climate change. Climate activists generally receive a lot of public support, even if it may recently have waned somewhat as a lot of people have started to view their protests as a form of coercion.

Critics point to the fact that there exists a democratic procedure in a representative majoritarian democracy, adding that anyone can play an active part in this system – vote, join a party, become a member of parliament – and thus influence procedures. They argue that those who break this democratically legitimized law are claiming a kind of moral high ground. In their view, this kind of protest is undemocratic because the activists believe the law does not apply to them in the same way as it does to others; this refusal to stick to the procedures, they say, is unconstitutional. However, several counter-arguments can be made against this criticism. The first is that any democratic procedure must be genuinely democratic, and not everyone is able to participate in a representative democracy. Let’s take asylum laws and migration policy for instance: Those directly affected, i.e. refugees and displaced people, cannot participate in these procedures. Generally speaking, at a very basic level, not everyone is able to participate in the political process to the same extent. As someone with a doctorate in law, I am able to articulate my opinion on the subject. For other people, it may not be so easy to persuade another person of something. To counter these structural or epistemic inequalities related to who gets to be heard, believed, and taken seriously, several ways of exerting a direct influence exist, which are also envisaged in the constitution – in Article 8 of Germany’s Basic Law on the freedom of assembly. This provision aims to compensate for the inequalities resulting from the representative procedure.

The logical next question would then be: What exactly is covered by this? How far am I allowed to go, what constitutes an assembly, and which forms of protest meet the requirements?

That question centers on how the constitution is interpreted, i.e. how we read the freedom of assembly! This is precisely what my work deals with: Of course, in the end, the final decision lies with the Federal Constitutional Court, but it is, in principle, possible to interpret the constitution. We live in a democratic constitutional state – those who live under the constitution also have a share in interpreting it.

Civil disobedience can manifest itself in multiple ways. If you were to drag people out of their cars, for instance, that would be overstepping the mark. What are the rules of the game?

Common conceptions of civil disobedience also formulate such rules, establishing certain yardsticks for proportionality: it must non-violent, should be symbolic, et cetera. In my work, I query some of these criteria; after all, the questions of what is non-violent, symbolic and proportionate also require interpretation. Many people label climate activists as very radical, likening their activism to force and coercion. The question is: Is that really the case? Does gluing oneself to the road constitute a use of force? According to the current legal rulings of the highest courts, merely sitting on the road constitutes a use of force. However, that opinion certainly could be questioned. According to this so-called “second-row case-law,” in preventing them from continuing on their journey, activists are using the first row of vehicles as a physical obstacle to jam the traffic from the second row onward. That’s a very complicated construct, which even lawyers in other countries have a hard time understanding, not to mention lay people. To get back to your example: climate activists don’t actually drag drivers out of their cars. Rather, it is the other way around: It is the drivers who actually drag the protesters off the road – an act that in fact constitutes a use of force! Applying physical force and injuring other people is no legitimate means of political communication.

Public debate is rife with expressions on the part of many citizens to the effect that they want to see the constitutional state take a tough line, and don’t understand why protests disrupting traffic are not simply broken up. Is it a case of a lack in basic legal knowledge to understand that the constitution is not set in stone, but always has to be interpreted?

I don’t think so. Everyone who thinks about this topic already has a sense of justice. It may well be very subjective, but my approach would be not to leave this interpretation solely to the experts. If, as a legal lay person, I think the word “force” doesn’t include sitting on a street, maybe I can provide arguments to support my view. Anyone can explain and state an opinion. Cases of civil disobedience can contribute to a better understanding of the constitution. After all, the law lives from cases that make it successively more specific. In the case of the “Letzte Generation” in particular, we can see that their activities relate to the constitution, namely to Article 20a of Germany’s Basic Law, which protects the natural foundations of life [Editor’s note: The “Letzte Generation” – i.e. last generation – is a group of climate activists from Germany, Austria and Italy].

Many citizens are worried by today’s forms of protest, which reminds them – justifiably or not – of the dramatic images of people storming the US Capitol to overturn the constitution.

I can definitely understand these concerns. There is such a thing as an authoritarian interpretation of the constitution: one exploits the constitution for non-constitutional purposes. During the “Querdenker” Covid protests, for instance, people were called upon to march on Berlin and join in the creation of a new constitution [Editor’s note: The term “Querdenker”, literally translated as “lateral thinker”, was initially coined to refer to those members of German society who protested against the country’s anti-pandemic regulations. It has meanwhile evolved to include comprises fringe elements questioning the legitimacy of the state]. Just because such authoritarian forms exist doesn’t mean there are no other, liberal forms of protest. The nice thing about jurisprudence is that, contrary to popular opinion, we lawyers don’t just think abstractly, but can also focus on the individual case at hand. In doing so, we are able to identify the differences between “Reichsbürger”, who use weapons, and climate activists gluing themselves to the road, who are basically using their own bodies’ vulnerability [Editor’s note: The term “Reichsbürger”, or Reich citizens, refers to anti-constitutionalist or revisionist groups that reject the legitimacy of the Federal Republic of Germany in favor of the German Reich].

Surely you are not justifying all forms of civil disobedience.

It is not up to me to judge whether the protesters always act in a way that makes sense politically. As a citizen I often wonder: what is it that you want to achieve? One thing I do want to draw attention to is the increase in criminalization – and that is not just my personal opinion. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association presented a report in 2021 stating that criminalization of climate activism is increasing worldwide. These forms of protest are being interpreted as force, as riots. More often than not, laws are amended not in response to Corona demos or the storming of the Capitol, but to Black Lives Matter protests and climate activism. Lawyers often like to say that everything must be viewed completely neutrally, that is, independently of the case. But it isn’t like that. Of course that doesn’t mean that the aim is to evaluate the issues politically. But there is a connection between purpose and means, which is inherent in an authoritarian way in one form of protest, but not in the other.

Questions: Dirk Frank

WERNER PÜNDER PRIZE

Awarded in memory of lawyer Dr. Werner Pünder, a staunch opponent of Nazism in Germany, the prize is presented annually to honor the best doctoral thesis, “Habilitation,” Master’s thesis or similar work at Goethe University Frankfurt, completed in the three most recent semesters in the field of “freedom and domination in the past and present.” A special focus lies on a topic concerning the foundations of law. The prize is worth 10,000 euros. Further information (in German).