75 years ago, the Allies issued the mandate to draw up a West German constitution – in the I. G. Farben Building

By Stefan Kadelbach

Shortly after the meeting in Frankfurt, the minister-presidents came together at Rittersturz Hotel in the hills above Koblenz from July 8-10 (from left): Louise Schröder (Berlin’s governing mayor), Jakob Stefan, Peter Altmeier and Adolf Süsterhenn (all Rhineland-Palatinate), Leo Wohleb (Baden) and Wilhelm Kaisen (Bremen).

Photo: picture alliance/ASSOCIATED PRESS/BAA

The constitutional history of the Federal Republic of Germany began in Frankfurt: 75 years ago, the military governors of the three Western powers presented three documents in the Eisenhower Hall of the I. G. Farben Building (now part of Westend Campus). These “Frankfurt Documents” included the mandate to draw up a constitution for a future Germany.

Even some of today’s more history-conscious members of Goethe University Frankfurt on Westend Campus are unaware of what happened here on July 1, 1948: On this day, the military governors of the Western Allies, Lucius D. Clay, Pierre Kœnig and Brian Robertson, handed over three documents to the minister-presidents of the West German states in the room since named “Eisenhower Hall” at the headquarters of the American Military Government. These documents have gone down in German constitutional history as the “Frankfurt Documents” (for further details, see Benz, Morsey, Mußgnug, Blank, Stern and Klein).

To place things in a historical context: In 1946, tensions were already mounting in the relationship between the three Western Allies and the Soviet Union. The Marshall Plan adopted in 1947 was rejected by Stalin for Eastern Europe, including the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. With the Treaty of Brussels, Britain, France and the Benelux countries formed a first Western defense alliance in March 1948. In the same month, the Soviet Union withdrew from the Allied Control Council. On June 23, 1948, the currency reform came into force in the Western zones, and on June 24, the Soviet Union began the Berlin Blockade. At the London Six-Power Conference, which took place between February and June 1948, the Western Allies decided to change their political stance towards Germany: The minister-presidents of the West German states were now to be authorized to “convoke a constituent assembly to be approved by the states” and its members were to be appointed by the state parliaments.

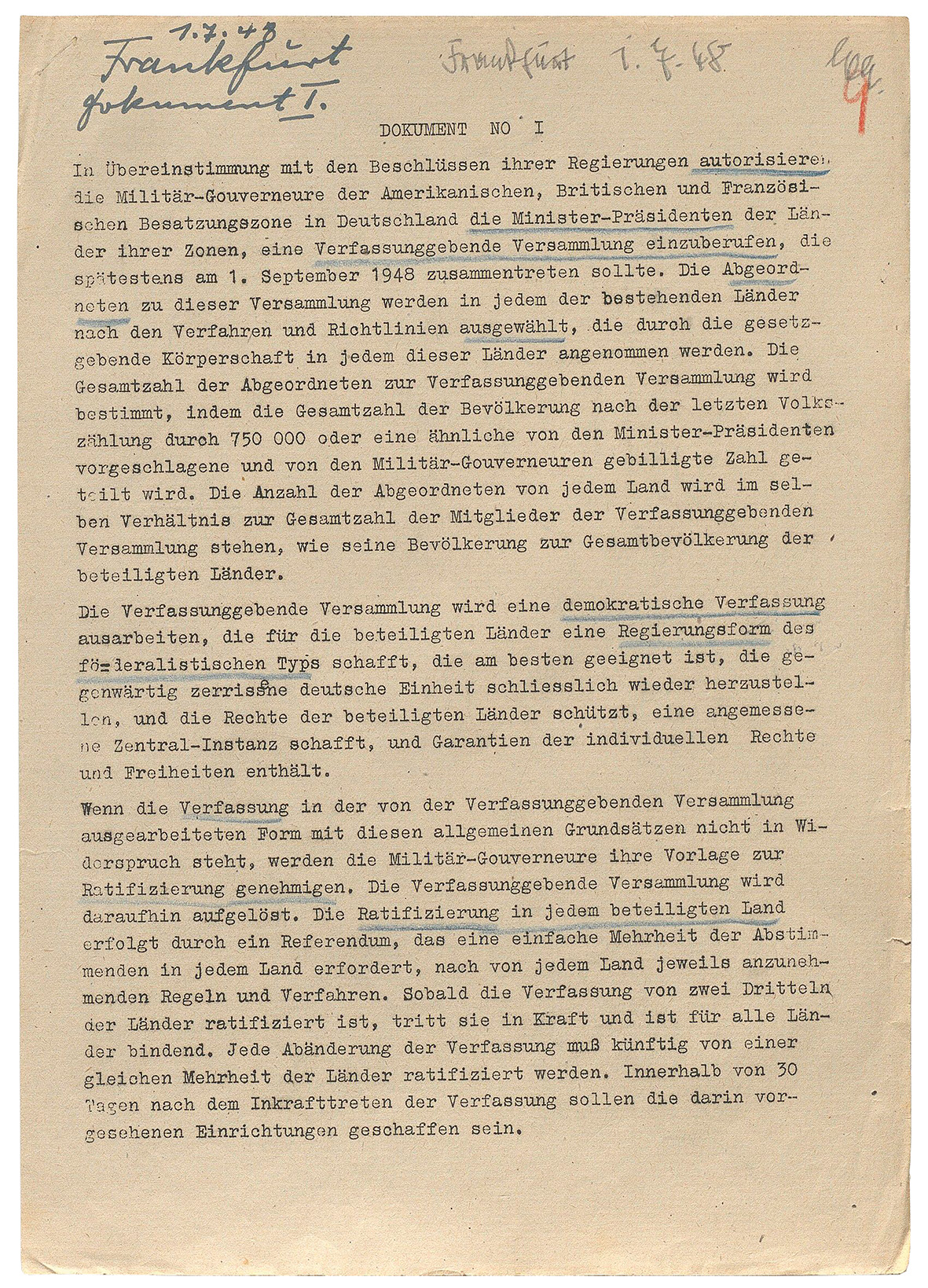

The aim of the Frankfurt Documents was to action the contents of these London resolutions. The first of the three documents pertained to the drafting of a German constitution, the second to a possible reorganization of the German states and the third to the Occupation Statute in Germany. The second document was resolved by the merging of the states of Baden, Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern to form Baden-Württemberg in 1952. The integration of Germany into the West through the General Treaty (also known as the Bonn-Paris Conventions) and Germany’s accession to NATO rendered the third document obsolete, as this ended the Occupation Statute as of May 5, 1955.

The most important document in terms of constitutional history is therefore the first one. It authorized the convocation of a constituent assembly “not later than” September 1, 1948, and set down requirements concerning democracy, rule of law and federalism. The Allies reserved some controlling rights for themselves, which also guaranteed them a right of access prior to the ratification of the constitutional document by the participating states. A referendum in the states was envisaged as the legitimizing act; a simple majority was to suffice in each case. After acceptance by two thirds of the states, the constitution would come into force.

The reaction of the minister-presidents was reserved. At a conference at Rittersturz Hotel in the hills above Koblenz on July 8-10, 1948, they criticized this approach as endangering German unity. By calling it the “Basic Law”, they aimed to emphasize that it was only a provisional arrangement. Furthermore, they did not think much of the planned referendums either and wanted the state parliaments to decide on the regulatory framework still to be developed. In turn, the Allies, first and foremost the USA, feared that this would weaken the constitution’s legitimacy. Pressurized by them and influenced by the Berlin Blockade, on July 26, 1948, the minister-presidents declared (again in Frankfurt) their consent to the referendum as a means of adopting the constitution “insofar as the Allied governments insist on holding a referendum”.

In August 1948, the state parliaments elected the members of the constituent assembly, known as the Parliamentary Council. The Herrenchiemsee Constitutional Convention, a commission of experts which met from August 10-23, 1948, was appointed to prepare the work. Although an initial draft in fact left the question of a plebiscite unanswered, the Central Committee rejected it. The solution that was then incorporated in the Basic Law, which allowed the state parliaments to decide on the constitution, was intended to express the provisional nature of the Basic Law, also as far as the procedure itself was concerned. There was a fear of turning the constitution into a matter of public contention. This fear was perhaps unjustified: According to a survey in the summer of 1948 commissioned by the “Neue Zeitung”, a newspaper published in Munich under the aegis of the USA, around 95 percent of respondents said they preferred to live in a free, democratic West Germany rather than under communist rule.

The text of the Basic Law was adopted in the Parliamentary Council’s plenary session on May 8, 1949. On May 12, 1949, the three military governors approved the Basic Law in a letter to Konrad Adenauer, the president of the Parliamentary Council. The referendum was no longer an issue. Of the eleven state parliaments at the time, the Bavarian parliament voted against it, as is well known, but it, too, acknowledged its validity in a further resolution. The new constitution came into force on May 23, 1949.

The Frankfurt Documents and the Basic Law

To what extent the Allies influenced the contents of the Basic Law is still contended today. Document No. 1 mandated the constituent assembly to “draft a democratic constitution which will establish for the participating states a governmental structure of federal type which is best adapted to the eventual re-establishment of German unity at present disrupted, and which will protect the rights of the participating states, provide adequate authority, and contain guarantees of individual rights and freedoms” (cited in German in Stern, p. 1215 f.). This vague formulation is the result of diverging ideas at the London Conference for which a common wording had to be found. However, and contrary to an initial misunderstanding on the part of the minister-presidents, the constituting elements formulated there were in themselves non-negotiable.

IN A NUTSHELL

• The three papers the military governors of the Western Allies presented to the West German ministerpresidents in the I. G. Farben Building on July 1, 1948, are known as the “Frankfurt Documents”. They included the mandate to draw up a constitution for the future Germany.

• According to the ideas of the Western Allies, the new Germany was to guarantee democracy, rule of law and federalism. A referendum was to endorse the constitution.

• The Herrenchiemsee Constitutional Convention prepared the text, which was adopted in the Parliamentary Council’s plenary session on May 8, 1949, and approved by the three military governors on May 12, 1949.

• To what extent the military governments influenced this process has been the subject of much debate and is still not entirely clear today. What is certain is that the Basic Law, originally intended as a provisional arrangement, has long since legitimized itself over the years, even without a plebiscite.

From indifference to constitutional patriotism

Does this mean that the corresponding contents of the Basic Law are the work of the Allies? Such claims were made in the early years of the Federal Republic, where three positions in German jurisprudence emerged (Spevack, p. 15 ff.): (1) the Basic Law as a dictate of the Allies, (2) the Basic Law as a compromise between the Allies and the German members of the Herrenchiemsee Convention and the Parliamentary Council, and (3) the Basic Law as an independent accomplishment of German constitutional culture. This debate and its development presumably also had to do with a habituation process in German society, which, as a historical study has traced, went from initial indifference in the late 1940s to gradual “tolerance” in the 1950s and a crisis in the 1960s to constitutional patriotism and normalcy since the 1980s (Spevack, p. 505 ff.).

Certainly, the members of the Convention and the Parliamentary Council were not constantly subjugated to instructions issued by the military governments. But there was a constant and discreet exchange between the two parties. Much of the Basic Law builds on older layers of constitutional history. This especially applies to fundamental rights, whose precursors partly date back to the Weimar Constitution and partly to the early 19th century. The republican form, parliamentary democracy and parts of the legislative procedure are a legacy of the Weimar Constitution, while other provisions in the Basic Law are to be understood as corrections of it, that is, they address its dysfunctional elements, such as the election of the Chancellor and the role of the Federal President. Other parts of the Basic Law, such as human dignity, provisions on citizenship, the basic right to asylum, the right to refuse to render military service on grounds of conscience and the right of resistance, are a reaction to the Unrechtsstaat, the unconstitutional state, of Nazi Germany. Some parts, such as the position of fundamental rights in the systematic framework, together with their direct applicability and enforceability, are new and independent concepts. The Federal Constitutional Court is another story. Here, the Allies’ wishes, first and foremost those of the USA, played a role, although such a court was already planned, and German constitutional jurisdiction is based much less on the model of the US Supreme Court than is, for example, the Swiss Federal Court.

Federalism was the only area where there was evidence of Western Allies’ attempts to intervene – perhaps that is why German federalism was perceived in the early years as a mere octroi, the states as artificial creations without historical roots. Wrongly so, as Germany has always consisted of individual states and has developed from a confederation of states (Holy Roman Empire, German Confederation) to a national federal state (since 1866/1871). The federal elements were no longer particularly pronounced in Weimar, not to mention the “coordination” (Gleichschaltung) of the states during the Nazi dictatorship. A centralized state was never a topic of discussion in the Parliamentary Council either; it was always just a matter of how to organize the new republic.

Nevertheless, the Allies issued two memoranda. One was concerned with federal legislation: Especially from the American perspective, the legislative powers of the Federal Government seemed too extensive – after all, legislative capacity in the USA always also implies administrative capacity, which would have meant considerable power in the hands of the Federal Government. According to the Basic Law, however, the states are responsible for the enforcement of federal laws, too. This concept is called compound federalism (Verbundföderalismus). The French Military Government, then again, was skeptical towards a strong federal power in the area of finance. It wanted the Federal Government to be financially reliant on contributions from the states. Presumably with the support of Britain’s Labour government for the Social Democratic Party’s adamant position, however, the Parliamentary Council largely remained loyal to its ideas. The Allies finally approved the text of the Basic Law nonetheless, which according to prevailing opinion had been only slightly amended (cf. Stern, p. 1336). Today, the German national federal state is still viewed critically on occasion: Most recently, in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, there was talk of an intentional “Kleinstaaterei” (territorial fragmentation) on the part of politicians and of “a patchwork” of policies. On the part of the states, too, there is often a reluctance to defend their own rights vis-à-vis the Federal Government, and intra-federal conferences apparently entail extensive coordination.

Nevertheless, the German model has clear merits. The greater proximity of the decentralized level to the matter in hand can assert itself in the administrative sovereignty of the states. This is also a question of identity. Starting with the redivision of Germany’s territory under Napoleon in 1803, the borders of its states have been radically changed five times (Blank, p. 325), and the states formed as the outcome were certainly not always organically grown entities in the past either. After 75 years, however, a new regional consciousness has developed. The second advantage of the national federal state lies in the greater number of levels of authority, which is referred to as the “vertical separation of powers”. It makes top-down government, “Gleichschaltung” and monolithic exercise of power difficult and improbable.

Legitimacy without a plebiscite?

The second point that was discussed as a result of the Frankfurt Documents is the question of legitimization: Who, according to the history of its development and the ensuing consequences, created the constitution, and was the Basic Law then a “real” constitution? According to the understanding of its fathers and mothers, it was only meant as an “administrative statute”, and the term “Basic Law” was intended to express a provisional arrangement. As described above, this does not yet make the Allies the creators of the constitution. However, the states were not its creators either, nor did their representatives want that role.

It has often been said that the adoption of a basic order requires a plebiscite, and that this alone ensures legitimacy. However, this is very rarely the case, both historically and empirically, and if so, it says little about the character of the adopted document. It is above all state practice and constitutional life that create legitimacy. This is also the view held today with regard to the Basic Law. The decisive factor is elections, in particular the first Bundestag election following the creation of the constitution, the exercise of government power legitimized by the Basic Law and the accepted practice of the constitutional bodies, as well as the application of the legislation issued and enacted under its provisions. What began with the Frankfurt Documents has long since legitimized itself.

This text is a slightly revised and abridged version of a public lecture on “75 Years of the Frankfurt Documents” held at Goethe University Frankfurt on June 30, 2023.

Literature

Benz, W.: Von der Besatzungsherrschaft zur Bundesrepublik: Stationen einer Staatsgründung, 1984, S. 214 ff.

Blank, B.: Die westdeutschen Länder und die Entstehung der Bundesrepublik, 1995, S. 27 ff.

Feldkamp, M.F.: Adenauer, die Alliierten und das Grundgesetz, München 2023.

Friedrich, C. J.: Rebuilding the German Constitution, Am Pol Sc Rev 43 (1949), 461 (462).

Klein, H.-H., in: Dürig/Herzog/ Scholz, Grundgesetz, Art. 144 GG Rn. 4 ff. (Kommentierungsstand 2017).

Kröger, K.: Die Entstehung des GG, NJW 1989, 1318 (1320).

Morsey, R.: Der Weg zur Bundesrepublik Deutschland, in: Jeserich/Pohl/v. Unruh, Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte Bd. V, 1987, S. 87 ff.

Mußgnug, R., in: Isensee/ Kirchhof, Handbuch des Staatsrechts Bd. I, 1987, § 6 Rn. 22 ff.

Stern, K.: Staatsrecht der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Bd. V, 2000, § 133.

Spevack, E.: Allied Control and German Freedom, 2000, S. 13 ff.

Wilms, H.: Ausländische Einwirkungen auf die Entstehung des Grundgesetzes, 1999, S. 198 ff.

The author

Professor Stefan Kadelbach, born in 1959, teaches constitutional, European and public international law at Goethe University Frankfurt, with a focus on foreign relations law, federalism, multi-level governance, institutional European law, human rights and general international law. He studied literature and law in Tübingen and Frankfurt am Main, and earned his doctoral degree in 1991 with a dissertation on “Peremptory Norms of Public International Law” and his habilitation degree in 1996 with a dissertation on “Administrative Law under the Influence of EU Law”. From 1997 to 2004, he was Professor of Public Law, International and European Law at the University of Münster; in 2004, he accepted a call to Goethe University Frankfurt. Kadelbach is co-director of the Wilhelm Merton Center for European Integration and International Economic Order and a member of the “Normative Orders” research center. From 2014 to 2016, he was rapporteur, and since 2017 he has been Co-Chairman of the Human Rights Committee of the International Law Association.