Retrospectively, it is often difficult to pinpoint exactly when order forms again after an uprising

by Andreas Fahrmeir

Photo: picture-alliance/akg-images

Sooner or later, every revolution comes to an end. A new order takes the place of revolutionary disorder. It is not easy to pinpoint exactly when this happens, not only because researchers are often more interested in the causes and motives of revolutions, but also because of how they end.

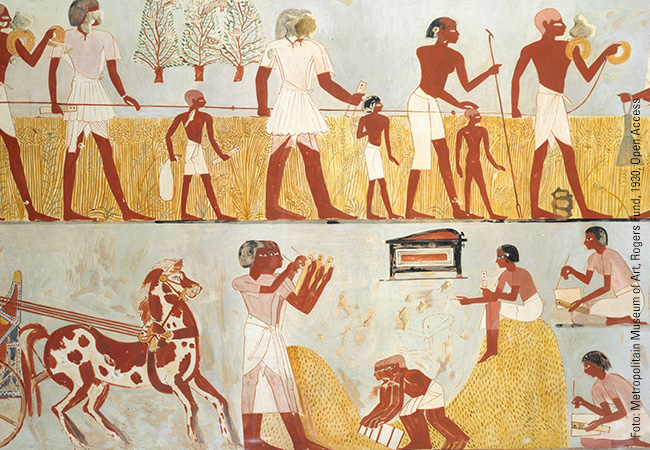

It is clear that the German revolutions of 1848 began in March. But when was stability restored? In May 1849, when important states such as Austria, Prussia, Hanover and Saxony recalled their representatives from the Frankfurt Paulskirchenparlament (Parliament of St. Paul’s Church)? In June 1849, when the remaining deputies, who had moved to Württemberg, were driven out of Stuttgart? In July 1849, when the campaign to impose the German parliament’s Imperial Constitution ended? In the autumn of 1850, when Prussia’s Erfurt Union project was abandoned? Or not until May 1851, when the German Confederation resumed its work unchanged?

At the beginning of a revolution, when it is unclear where political power lies, upholding the previous order becomes impossible. In March 1848, faced with widespread public protests, most of the authorities in the German states had considerable doubts whether they would survive a confrontation, as they were uncertain if they could rely on the military and the civil service. As a result, they made far-reaching concessions – which in turn meant that most monarchs, commanders and civil servants remained in office.

New institutions, old instruments of power

In the course of the revolution, the draft plans for the future developed in parliamentary debates, and public discussions met with approval, but also with opposition, which even stretched to violent attacks on new institutions and their representatives. Consequently, some of these institutions began to rely more heavily on the existing instruments of power than they had initially considered necessary: After the violent death of two deputies in Frankfurt on September 18, 1848, the democratically legitimized Frankfurt Parliament found itself as dependent on the protection of the Prussian and Austrian garrison as the monarchical Federal Assembly had been.

The refusal of the imperial crown by Prussian King Frederick William IV at the beginning of April 1849 occurred in a climate of political polarization and fueled it further. In many Prussian cities, there were vigorous clashes between groups willing to continue supporting their deputies in the Frankfurt Parliament and ones that welcomed the end of the pan-German consultations on the constitution.

Defense leagues should complete the revolution

The campaign for the German Imperial Constitution in May 1849 was an attempt to revive the mood of March 1848. While the Frankfurt Parliament appealed on May 6 to “the legislative bodies, the municipalities and the entire German people” to enforce the Imperial Constitution, delegates of the Märzvereine parties underlined this demand by calling for the establishment of “defense leagues” of armed men. However, the response was significantly lower than in March 1848. Only in a few regions – in Saxony, the Bavarian Palatinate and Baden – was it possible to stand up to the monarchical authorities (which were now much more secure in their military resources), at least temporarily.

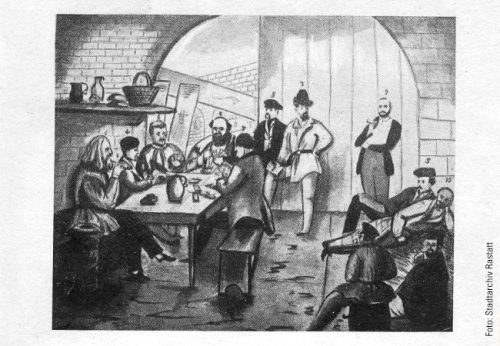

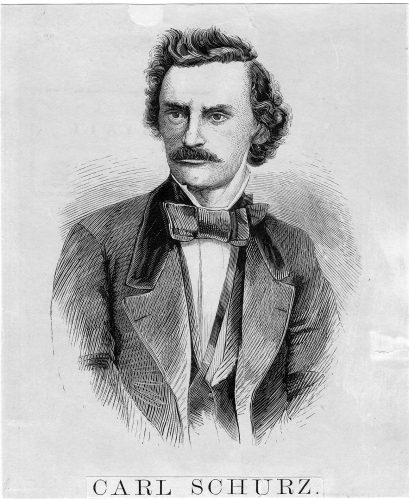

Like a beacon, the Republic of Baden, which existed from May 1849 until the capitulation at Rastatt Fortress on July 23, 1849, attracted many activists from the republican left from western and southern Germany. Although significant parts of the Baden military supported the Republic and elections to a constituent assembly in June were intended to guarantee broad legitimacy, the Prussian military proved stronger. Carl Schurz, the radical Democrat and Bonn student, was stationed at Rastatt as one of the officers of the Republic and initially able to hide after the capitulation before escaping to Switzerland. In his memoirs, which were only published in 1907, he commented on the limited support for the republican experiment among the population. In his opinion, this was because the abolition of feudal duties (i.e. levies or labor obligations to feudal lords) in the spring of 1848 had fulfilled a central requirement for all rural areas, even if the actual implementation was delayed. The handover of Rastatt Fortress took place without a fight – at least in Schurz’s account – out of consideration for the civilian families living in the city who were not directly involved in the revolution. (However, it was precisely thanks to these uninvolved parties that he was not handed over to the Prussian troops but instead able to flee.)

Prussia’s monarchy calls for a new order

However, revolutionary disorder also opened up new possibilities for the rulers, the Prussian monarchy, for example. At least in terms of rhetoric, it had already positioned itself at the head of a German national movement in the spring of 1848. Its goal was to combine the geopolitical outcome of the Frankfurt Parliament – a union of all German states excluding Austria under Prussian leadership – with a more conservative constitution. To this end, government negotiations on the content of such a constitution took place from May 1849 onwards; elections for a second national parliament, held under the three-class franchise and thus boycotted by the political left, followed in the winter of 1849/50. The deliberations of this Parliament of the German Union at Erfurt began on March 20, 1850, and ended on April 29 after the adoption of the constitution and the submission of amendments.

What Berlin saw as a transition to a new order was deemed by Vienna to be a continuation of disorder. As a result, this constitution was never implemented either. Archduke John of Austria, elected as Imperial Regent on June 28, 1848, as the interim head of a provisional German government, only resigned in December 1849, but not in favor of the King of Prussia, as was hoped in Berlin. Rather, his powers – including the nominal control of German troops in Schleswig-Holstein and the fortresses of the German Confederation – were transferred to a federal commission agreed in September 1849 and made up of an equal number of representatives from Austria and Prussia. This commission was to bring about either a return to the previous German Confederation or an alternative constitutional order by May 1, 1850. The question of which constitution now governed relations between the German states, whether interventions by a group of states in favor of or against existing constitutions were lawful or unlawful, dominated German politics during the further course of 1850, until the return to the German Confederation was enforced, against the backdrop of mobilization in Prussia and Austria under massive Russian pressure.

Only gradual stabilization

For the stakeholders of the 1848/49 revolutions, these steps led to very different sanctions, which became stricter over time: In Baden, punishment or forced exile was swift and particularly brutal, while in Prussia, the government sought cooperation with the more conservative parts of the liberal opposition for longer, until the latter also came under greater pressure as the prospect of a “German Union” disappeared. Depending on which dimensions of political order are highlighted – institutions, legitimacies or incumbents – there are thus very different endings (not just after 1848). While at the beginning of a revolution all three are under pressure simultaneously, their later (re-)stabilization often takes place at very different times.

The author

Professor Andreas Fahrmeir, born in 1969, has been Professor of Modern History with a particular focus on the 19th century at the Institute of History, Goethe University Frankfurt, since October 2006. Fahrmeir studied medieval and modern history, history of natural sciences and English philology at Goethe University Frankfurt. He earned his doctoral degree in Cambridge in 1997, after which he worked at the German Historical Institute London (GHIL). Following his habilitation in 2002 in Frankfurt, he held a Heisenberg scholarship of the German Research Foundation (DFG) until 2004. From 2004 to 2006, he taught as Professor of European History of the 19th and 20th Centuries at the University of Cologne. His research focuses on the city and the bourgeoisie, British and German-British history, migration history and political history of the 19th century.