A subproject in the Priority Program “Visual Communication” endeavors to make body language analyzable

Gestures help people under-stand each other. They are also increasingly important for human-machine interaction.

All photos: Uwe Dettmar; all other photos: Technology Lab

Visual means of communication such as gestures and facial expressions are age-old forms of human understanding. When someone speaks, they not only string words or sentences together but also use their hands, arms, head and face. ViCom, a Priority Program at Goethe University Frankfurt funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), has been studying these nonverbal channels since 2021. One of the subprojects is examining the significance of body language with the help of virtual reality (VR) recording methods.

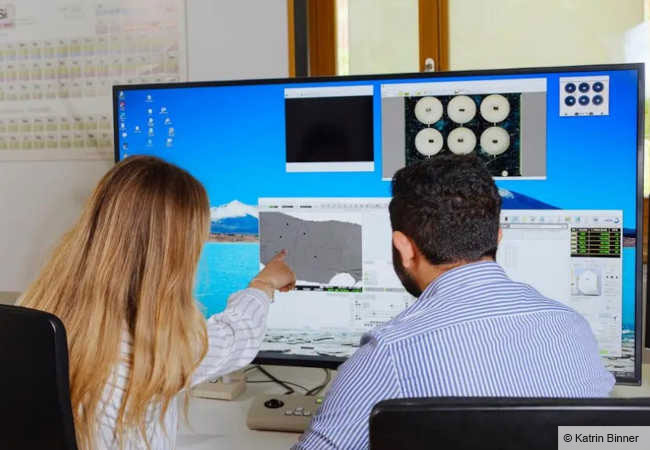

Transitioning from the office in the Faculty of Computer Science and Mathematics to the virtual world takes only a few seconds: The test person (in this case, the author) just puts on her VR goggles and is suddenly an avatar standing on a street that runs through a small town – past a chapel, through the park to the church and onwards to the town hall. Her task then is to describe the way to another test person so that they can follow.

For computer linguist and computer scientist Professor Alexander Mehler, linguist Dr. Andy Lücking and computer scientist Dr. Alexander Henlein in Frankfurt, the dialogs taking place in the VR lab can deliver valuable insights: What role do gesticulation and facial expressions play when describing the way? How is spoken language combined with pointing, facial cues or other nonverbal instructions? Which route does the second test person take and what helps them to arrive at their destination? These are questions that researchers in the GeMDiS project (Virtual Reality Sustained Multimodal Distributional Semantics for Gestures in Dialog) want to answer.

Pointing – a clear gesture even in early childhood that the computer must first learn with the help of VR technology.

Gestures: Long neglected by linguistics

Although gestures were long regarded in linguistic research as mere accessories to verbal utterances, we know today that they are much more than that. There is a difference between a guest in a restaurant saying “The food is too salty” and banging his fist on the table as he says it. “We use gestures and facial expressions because they enable us to convey more information and make communication more efficient,” says Alexander Mehler, and gives another example: “If I want to talk to my interlocutor about a certain plant, I automatically look or point in the corresponding direction. This makes it easier to identify the object without wasting a lot of words.”

This is exactly what most of the test persons also do when describing their route in the VR trials. In countless experiments, the GeMDiS team has observed, for example, that the participants use their hands to form a triangle when saying the word “church” to describe the roof more expressively. To indicate a pond in the virtual landscape, they draw a circle with their finger. The project hypothesizes that the more frequently the first test person couples spoken language with gestures and facial expressions, the more easily the second test person can follow the way.

Restricted gestures – less understanding

The GeMDiS team can also use virtual reality technology to explore what happens when body language is restricted. For example, the test person’s auditory and visual ability can be influenced by manipulating the audio and video outputs of the VR goggles. It is also possible within the VR environment to influence to what extent they can grasp and use objects virtually: In one of the experiments, for example, the test person could no longer pick up a virtual cup from the table. The researchers discovered that such restrictions of a person’s ability to act have a major impact on communication that is not, by contrast, seen when restricting auditory and visual quality via technical means: Test persons whose possibilities for interaction are curtailed move around far less in the virtual world, they talk more about their experiences there and are generally more negative in their assessment of how they experienced the experiment.

Each test series in experiments of this kind lasts around 25 minutes. The GeMDiS team then looks in detail at the image sequences and analyzes them. The computer delivers data on hand and face movements from this three-dimensional space. These data are used over the course of the project to train artificial intelligence (AI) models. The AI recognizes when examples frequently recur – like when a word such as “tree” or “crossroads” is often combined with a specific gesture when describing the way.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Experiments based on virtual reality (VR) have demonstrated that the combination of verbal language and body language (e.g. gestures) greatly improves comprehensibility and orientation, for example when giving directions.

- In subsequent experiments, the test persons‘ ability to perceive gestures or facial expressions in the VR environment was restricted via technical means. The outcome was that communication was less effective, and participants‘ overall perception of how they experienced it was more negative

- The GeMDi project uses AI to recognize patterns in the combination of verbal and nonverbal language. In the process, the different communicaiton signals are mapped in a common, mulitmodal semantic space.

- The aim is to establish a form of corpus linguistics that integrates spoken and nonverbal language and to use the resulting semantic space as the basisi for multimodal AI, e.g. to create a corresponding language-gesture lexicon or for improved human-machine interaction.

Once trained, the AI should recognize patterns

To do this, the AI generates something called a multimodal similarity space, a kind of mathematical or geometric representation of the collected data, which makes it possible to compare different linguistic signs, such as words, sentences or grammar, and nonverbal signs, such as gestures, facial expressions or body posture. “The advantage is that this similarity space also provides areas for things that are not said or expressed as gestures. The AI does not have to monitor these areas, but they make it easier to recognize more and more new gestures or language data,” explain the scientists. In this way, things that were not detected when the algorithms were trained can nevertheless be “recognized” later.

Here, the computer scientists and linguists in Frankfurt are using a method long common in spoken and written language: corpus-based linguistics. This involves analyzing language data from large collections of texts, referred to as corpora. The aim is to recognize patterns – for example, at the level of grammatical structure or word frequency. To make predictions, they also analyze how linguistic and non-linguistic units relate to each other. This method makes it possible to document even the finest changes in language or to visualize how expressions are used in different contexts. This is not simply a playground for theorists but instead can help in practice to improve communication between humans and machines – in speech recognition systems, for example, or systems based on gesture control.

Gestures have a broad bandwidth

Because corpus linguistics has to date dealt far less with the analysis of nonverbal language such as gestures or facial expressions, there is a lack of corresponding corpora. That is why the GeMDiS team wants to contribute to closing this data gap with the help of multimodal corpus linguistics, that is, by analyzing spoken and nonverbal language in combination. As far as the methodology is concerned, this is a challenging task. While spoken and written language are concerned with understanding each word with its assigned meaning, visual communication is far more complex. “Gestures that accompany speech are not prescribed or codified, in contrast to sign language, for example. Pointing gestures, for example, have very different meanings depending on the context,” explains Professor Mehler. “Unlike in spoken language, form variance is also vast. Gestures are not always the same. For example, if I have injured my hand, I point differently than I would without that restriction.” In addition, a gesture’s meaning can vary depending on where it is used and by whom. Nodding your head means you agree? Not always. In Greece, for example, it means “No” and not “Yes”.

Let’s get back to gesture research in the VR lab in Frankfurt. The GeMDiS team still needs to observe a lot of dialogs in the virtual world as well as collect and analyze multimodal information so that other scientists can also work with the wealth of data in the future. In the long term, the results of the ViCom subproject should contribute to facilitating human-machine interaction. But the research project might also produce a multimodal gesture lexicon, a bit like a dictionary for a foreign language. The idea, for example, is to use images such as shaking hands, bowing, or similar symbols to represent various forms of greeting.

Furthermore, the VR-based recording technology at Goethe University Frankfurt could yield interesting findings for sign language. In collaboration with the University of Cologne, the GeMDiS team wants to shed light on the role of mouth movements when describing a route. For deaf people to understand what is being said, such gestures are very important. Mouth images and mouth shapes are an integral part of sign language.

Visual Communication

»As philosopher and communication theorist Paul Watzlawick once said: “One cannot not communicate.” Even when words fail, people convey messages with their body. The Priority Program “Visual Communication” (ViCom) funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) examines this nonverbal form of communication in greater depth. In a collaborative project between Goethe University Frankfurt and the University of Göttingen, researchers from various disciplines are investigating, for example, commonalities between gestures and sign language, the effects of gestures in didactic or therapeutic contexts, animal communication, and how human-computer interaction works. The aim of ViCom is to develop a new model that captures the multi dimensionality of communication.

About

Prof. Dr. Alexander Mehler has held the Chair for Computational Humanities/Text Technology at Goethe University’s Faculty of Computer Science and Mathematics since 2013. He earned his doctoral degree in computational linguistics at Trier University. His research interests include the quantitative analysis, simulative synthesis and formal modeling of textual units in spoken and written communication. In this context, he studies linguistic networks based on contemporary and historical languages (using language evolution models). One of his current research interests is 4D text technologies based on virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and augmented virtuality (AV).

mehler@em.uni-frankfurt.d

Dr. habil. Andy Lücking is a private lecturer and principal investigator in Goethe University Frankfurt’s Text Technology Lab. He studied linguistics, philosophy and German philology at the University of Bielefeld and earned his doctoral degree there with a dissertation on multimodal grammar extensions. He worked as a postdoctoral researcher in computational linguistics/text technology and defended his postdoctoral degree (Habilitation) at the Université Paris Cité with a dissertation on “Aspects of Multimodal Communication”, in particular a “gesture-friendly” semantic theory of plurality and quantification. Lücking is especially interested in the linguistic theory of human communication, that is, the face-to-face interaction within and beyond single sentences, paying particular attention to various kinds of gestures and cognitive modeling.

luecking@em.uni-frankfurt.de

Dr. Alexander Henlein is a postdoctoral researcher in the Text Technology Lab. As a computer science student at Goethe University Frankfurt, his main interest was computer speech recognition. His dissertation explored text-to-3D scene generation and the question of how three-dimensional worlds can evolve from language. He is currently dealing with multimodal language and communication, especially in conjunction with modern language models, and working on the development of a VR-based system to collect and analyze multimodal data.

henlein@em.uni-frankfurt.de

The author

Katja Irle, born in 1971, is an education and science journalist, author and moderator.

irle@schreibenundsprechen.eu

Zur gesamten Ausgabe von Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Sprache, wir verstehen uns!