How much intervention can order tolerate, how much freedom does order need?

by Stefan Terliesner

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke in the Bundestag of a “turning point

Photo: picture alliance/dpa/Michael Kappeler

The war in Ukraine has exposed Germany’s weaknesses mercilessly. Yet economic order still prevails and is leading the way out of all the crises. An analysis with economic experts from Goethe University Frankfurt.

Putin cannot be blamed for everything. Although the phrase “turning point” is closely linked to his war of aggression against Ukraine, several challenges that Germany is now facing in relation to this term – inflation, energy prices, climate, infrastructure, etc. – were already emerging well before February 24, 2022 (the start of Putin’s war) and thus also before February 27, 2022 (the day Chancellor Scholz gave his “turning point” speech). The Ukraine war has exposed and aggravated Germany’s weaknesses. European media are already alluding to the “sick man of Europe”. Are those responsible in politics aware of how serious the situation is? And are the right conclusions being drawn? Did a “turning point” really follow the Chancellor’s speech?

Functional and shock-resistant economic framework

Theoretically, a country with a functioning economic framework is able to absorb external shocks at any time and steer them into productive channels. After a period of disorder, life returns to normal. Times change and the economy adapts. Problems in terms of loss of prosperity for the general public arise above all when necessary adjustments are prevented – for example, by well-organized vested interests that influence political decisions.

The economist Walter Eucken, pioneer of the social market economy and founder of ordoliberalism, formulated the principles of such an order (see diagram, p. 40: “Clear Order”). The basic idea was that the state should shape economic order and not steer economic processes. Ludwig Erhard, the first Minister of Economic Affairs and second Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, put important principles from Eucken’s work into practice, for example, in the course of the monetary reform 75 years ago, free pricing on the basis of supply and demand, and the antitrust law in 1957. Although research in Germany has advanced since then, at its core, Eucken’s principles continue to contribute to a functioning economy and a free society.

Putin’s attack on Ukraine was initially also a shock to the economy. “The German economic model, which is based on a strong industrial sector and an international division of labor, has come under pressure,” wrote Michael Heise, honorary professor at Goethe University Frankfurt, in a newspaper article for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s “Die Ordnung der Wirtschaft” (“Economic Order”) section on November 25, 2022. This uncertainty, he said, was mainly triggered by a surge in consumer prices by 10.4% in October 2022. In particular, food, gas, heating oil and electricity prices soared – an “existential threat to many private households, businesses and energy-intensive companies,” said Heise.

State aid on a massive scale

The German government responded with support measures amounting to almost €300bn (see box: “Extensive Relief Packages”, p. 41). To put this enormous sum into perspective, the total federal budget for 2023 was €476bn. The biggest chunk of the state aid package was the €200bn defense package agreed in September 2022, which the government did not record in its budget but under the misleading term “special funds”; in fact, it is (potential) debt. The government raises funds on the capital market. In return, purchasers of government bonds receive interest from the taxpayer.

This was facilitated by a credit authorization, which the Grand Coalition had already set up under the name Economic Stabilization Fund as a protective shield against the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. The current coalition changed its intended use: Instead of coronavirus relief, there is now a price cap for electricity and gas of 80%. Households and companies pay the remaining 20% in accordance with their utility contract – so that there is at least a small incentive to save energy. Even during the crisis, the government was evidently reluctant to completely eliminate the market price mechanism.

By the end of 2022, the situation on the energy markets had already begun to ease. Gas and electricity prices have meanwhile fallen sharply. Chances are that the German government will have to pay less aid than feared. Several factors have contributed to the situation easing: Companies and consumers have saved energy, and the winter of 2022/23 was mild. Further, two new terminals for liquefied natural gas (LNG) sourced by ship from overseas were built in under six months. A lot of gas is now also flowing into Germany from Norway and the Netherlands via pipeline. Before the war, Germany sourced 55% of its gas imports from Russia; at the end of 2022, almost none. This shows clearly how open markets secure supply.

Inflation accelerated by war

At the time of this assessment, in mid-2023, what was causing economists a headache was persistently high inflation and the lack of energy suppliers in Germany. Volker Wieland, Endowed Professor of Monetary Economics and Managing Director of the Institute for Monetary and Financial Stability (IMFS) at Goethe University Frankfurt, had already warned of significantly rising inflation a year before the Ukraine war. “War and the energy crisis were only the accelerant to 10% inflation in 2022,” he says in retrospect. According to figures from the Federal Statistical Office, the inflation rate in Germany was 4.9% in December 2021 and 3.1% in 2021 overall. For the first time since 2011, the annual inflation rate was above the European Central Bank’s (ECB) target of 2%.

Wieland claims that the foundation for inflation was laid in the coronavirus crisis – mainly through government relief packages and cheap money as a result of the ECB’s zero interest rate policy and asset purchase programs. In addition, shifts in consumption and production have led to supply bottlenecks in a number of industries, he said, and scarce supply drives up prices. Wieland believes that the ECB should have responded earlier to rising inflation by raising the key interest rate.

The first increase in the main refinancing operations rate took place after the outbreak of war on July 21, 2022, from 0 to 0.5%. It has meanwhile climbed to 4.5% – a very steep rise as the ECB had to act quickly. As a result, borrowing for households and companies has become more expensive, consumption and investment are declining, and economic growth is slowing. Researchers believe that a recession in Germany is likely, a prolonged phase of contraction with less production, income and tax revenue.

Inflation particularly hurts the less affluent

However, simply lowering interest rates again is not an option for most people. Inflation devalues savings and reduces purchasing power. This mainly affects people with low and middle incomes who cannot fall back on tangible assets such as shares and real estate. Against the background of experiences with inflation in the 1920s and 1970s, there is increasing international consensus that central banks should be independent of political instructions and primarily committed to safeguarding the value of money.

Jan-Pieter Krahnen, the Founding Director of the Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE at Goethe University Frankfurt, and his successor as scientific director, Florian Heider, are convinced “that the ECB will keep interest rates high until its 2% inflation target appears achievable.” The ECB itself expects this target to be reached in early 2026. The two economists also agree that monetary policy is the primary task of the central bank. Heider criticizes that secondary objectives at the ECB, such as climate protection, redistribution or growth, play too great a role: The ECB is “not the right place” for this. In a functioning economic order, the most suitable instrument must be used in each area, and this tends to be fiscal policy under political responsibility rather than the monetary policy of the central bank. With fiscal policy, a government tries to compensate for economic fluctuations with the help of taxes and government spending.

The European Central Bank in Frankfurt is fighting inflation by increasing interest rates.

One-off payments are not an inflation risk

Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln, Professor of Macroeconomics and Development at Goethe University Frankfurt and a labor market expert, also recognizes “a clear commitment to fighting inflation” at the ECB. This is another reason why she hopes “that we will be spared a wage-price spiral”. Recently, it was higher wages, rather than rising energy prices, that fueled inflation, as employees are compensating in this way for the decline in real earnings. Heider points out that employers and trade unions have also agreed on one-off payments in the current collective bargaining agreements. “This ameliorates the wage-price spiral slightly.” The conclusion is that collective bargaining agreements in Germany seem to be working.

But the high electricity costs in Germany compared to the USA and Asian countries are a persistent problem. In 2023, the call from politicians, trade unions and corporate bosses for an industrial electricity price or a temporary electricity price cap for industry grew louder and louder. Energy-intensive companies should have to pay significantly less for electricity until enough electricity from renewable sources is available at low prices, they said. Further public debts of €30bn by 2030 remain on the table.

EXTENSIVE RELIEF PACKAGES

With measures totaling almost €300bn, the German government is containing energy costs and safeguarding jobs. An overview.

• December 2022 energy bill rebate to bridge time until the gas price cap

• Gas price cap since January 1, 2023, for households and companies

• Electricity price cap since March 1, 2023, for households and companies

• Extension of consumption peak equalization scheme for energy-intensive manufacturers

• €3,000 tax-free one-off payment by companies to their employees

• Energy tax reduction (reduced tax rate for gas)

• Energy allowance (€300 one-off payment for students)

• One-off citizen’s benefit payment in July 2022

• Child benefit of €250 per child per month; special supplementary allowance of €20

• More housing allowance for two million households; permanent heating costs component

• Higher commuter allowance; national ticket for public transport (Deutschlandticket)

• Mini-job limit increased to €2,000 (higher net income)

• Heating subsidies for two million people (€230, then another €345)

• Inflation compensation (tax burden adjusted for inflation; higher allowances)

• Pension contributions from 2023 fully tax-deductible

• Home office tax allowance increased and made permanent

• Compensation from unemployment insurance for reduced income (short-time work allowance)

• Industrial electricity price (decision not available at the time of writing)

Source: Federal Government

Is it time to abolish the electricity tax?

Alfons Weichenrieder, Professor of Economics and Public Finance at Goethe University Frankfurt, rejects the idea of preferential treatment for a few companies and sectors. Instead, he proposes that the electricity tax introduced in 1999 should be completely abolished. “In addition to small companies, this would also relieve private households, which have so far lost out as far as climate bonuses are concerned,” says Weichenrieder. Switzerland, for example, uses climate bonuses to compensate for price increases resulting from the energy transition.

Weichenrieder refers to a statement by the Advisory Board to the Federal Ministry of Finance, of which he is a member, as are his colleagues Krahnen and Wieland. If the industrial electricity price were subsidized by the state, there would be a risk that necessary structural adjustments would not be made. After all, energy-intensive companies in Germany have already received billions in compensation for the high electricity prices, insofar as these result from the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme for CO2. Further subsidies would put funds that are “urgently needed for the expansion of the energy infrastructure into managing the deficiency instead of remedying it, so to speak.”

To reduce energy prices and facilitate CO2 reductions, electricity supply must be expanded. Weichenrieder thinks it is time to “radically simplify and accelerate approval procedures for the production of renewable energies.” Almost all economists believe that European emissions trading is an effective and efficient instrument for climate protection. It encourages reductions in CO2 emissions and helps minimize costs to the European economy. The total emissions of the sectors affected by emissions trading are capped at the politically agreed level.

Scant support for a capital markets union

Krahnen agrees that the key to the further development of competitive and resilient financial markets lies first and foremost in Europe. For years, he has been campaigning for the creation of a capital markets union for the EU and for the completion of its banking union. “There is still a lot to do here, but unfortunately the will is lacking – especially in Germany,” he admits. In Krahnen’s view, effective measures would require a “big bang” for a centralized European capital market supervision. This adds to the necessity to waive some sovereignty in matters of banking supervision and resolution.

Nevertheless, there is hope. “We are currently living in an era of great uncertainty with an equally high need for orientation, and this also and especially among the general public. It is also a good time to bring further order to the financial markets and in this way ultimately increase prosperity and welfare in our society and in the EU as a whole,” says Krahnen. This also describes large parts of SAFE’s research program, which is also highly topical in view of the association of countries such as Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova currently under discussion.

IN A NUTSHELL

• The social market economy’s principles of order guarantee freedom and prosperity for all. They also provide the flexibility to cope with crises and shocks.

• Walter Eucken’s basic idea: The state shapes economic order and does not steer economic processes.

• Putin’s war on Ukraine has exposed Germany’s weaknesses. The German government responded to the shock of the war with massive state aid.

• By the end of 2022, the situation had already eased, partially because Berlin did not completely override the price mechanism and partially because companies and private households saved a lot of energy.

• The ECB fights inflation by raising the key interest rate. Borrowing becomes more expensive and economic momentum slows. As a result, prices ought to start shrinking again.

• An EU capital markets union could make financial markets more resilient. SAFE is contemplating how such a framework might look.

SAFE is contemplating how a European regulatory framework might look “within which countries can help each other but are still independently liable for their own financial conduct.” With the help of a capital markets union, ample private capital could be generated from all over the world. This would be important for mastering upcoming challenges such as rebuilding Ukraine and the “green” transformation of the economy. Such vast sums cannot be financed by state budgets alone, i.e. solely through taxes and debt.

In conclusion, to solve challenges such as inflation, the energy crisis, climate change and infrastructure, it is necessary to pay attention to and to a certain extent also return to basic regulatory principles. Then Germany would soon regain its usual strength. However, the whole of Europe must become more resilient to economic crises. Experts in Frankfurt, too, are working on the regulatory framework needed to achieve this.

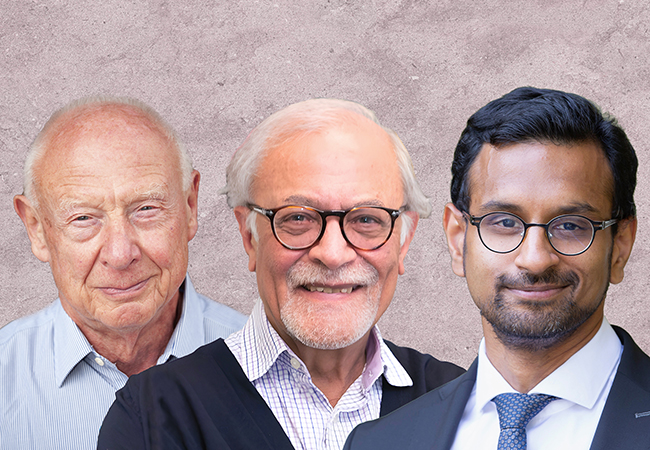

Our experts

Volker Wieland has been Endowed Professor of Monetary Economics at the Institute for Monetary and Financial Stability (IMFS) at Goethe University Frankfurt since March 2012. He is also Managing Director of the IMFS. Wieland studied in Würzburg, Albany, Kiel and Stanford. In 1995, Stanford University awarded him a PhD in Economics. Before coming to Frankfurt at the end of 2000, he worked as a Senior Economist on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve in Washington, USA.

Jan-Pieter Krahnen is the Founding Director (em.) of the Leibniz Institute for Financial Market Research SAFE and Professor (em.) of Finance at Goethe University Frankfurt. Krahnen served on the European Commission’s High Level Expert Group on Structural Reforms of the EU Banking Sector (Liikanen Commission) in 2012 and on the Expert Group “New Financial Architecture” (Issing-Commission) from 2008-2012. He is also a member of the Advisory Board to Germany’s Federal Ministry of Finance.

krahnen@finance.uni-frankfurt.de

Florian Heider has been Scientific Director of the Leibniz Institute for Financial Market Research SAFE and Professor of Finance at Goethe University Frankfurt since December 2022. His main research interests are financial intermediaries, including their role in monetary policy, as well as market design and the capital structure of companies. Following positions at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the New York University Stern School of Business, he held various positions at the ECB from 2004 onwards.

Alfons J. Weichenrieder teaches finance at Goethe University Frankfurt. He is also a guest professor at Vienna University of Economics and Business and a research fellow at the Leibniz Institute for Financial Market Research SAFE. He has been Deputy Chairman of the Advisory Board to Germany’s Federal Ministry of Finance since 2023. His research focuses on tax and fiscal policy with points of contact to environmental and redistribution issues.

a.weichenrieder@em.uni-frankfurt.de

Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln is Professor of Macroeconomics and Development at Goethe University Frankfurt. Before coming to Frankfurt in 2009, she was an assistant professor at Harvard University. She received her doctoral degree in economics from Yale University in 2004 and an honorary doctorate from Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg in June 2023. In 2018, she was awarded the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, the highest scientific award in Germany.

Michael Heise is an honorary professor at Goethe University Frankfurt and Chief Economist at HQ Trust. Prior to that, he was head of Group Center Economic Research at Allianz SE and Secretary General of the German Council of Economic Experts.

The author

Stefan Terliesner, born in 1967, is an economics graduate and freelance business and financial journalist.