The U.S. scientists Dr. Erica and Prof. Justin Sonnenburg will visit Goethe University in November to take up the Friedrich Merz Visiting Fellowship. Their research focuses on small organisms that exert a huge influence on our life and health.

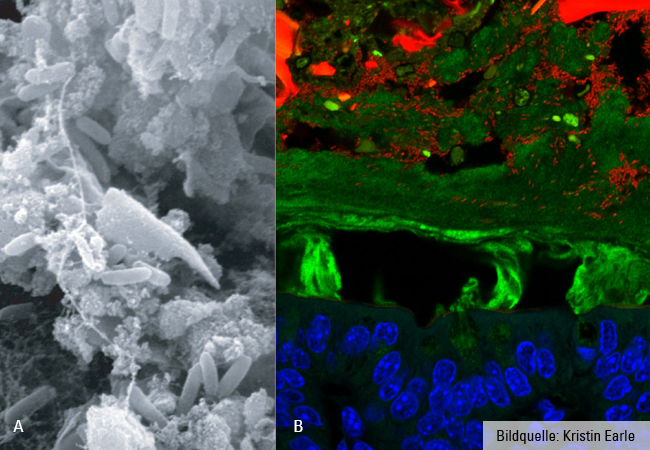

Image A: B. theta embedded in mucus with food particles. Picture: Jamie Dant and Justin Sonnenburg

Image B: B. theta wandering about in the gut. Small red rods: B. theta; green: mucus; blue: host epithelium/colonocytes.

Picture: Kristin Earle

The “gut microbiome” is the name given to the entirety of microorganisms that colonize our gut. Each of us is home to anything between 10 and 100 trillion microbes – such as viruses, archaea and fungi, but principally bacteria. We humans live in symbiosis with this collection of microscopic inhabitants of our gut, which together form an ecosystem and a community providing valuable services for human beings. This ecosystem helps to keep our immune system healthy. It’s also involved in metabolism. It even “talks” to our brain, using specific communication channels to send and receive information, and in this way the gut microbiome could also influence our emotional state.

Erica and Justin Sonnenburg from Stanford University in California have spent many years researching exactly how our symbiont functions, which diseases result from dysbiosis, i.e. a gut microbiome that is out of balance, and what new treatments or medicines might be available for treating them in the future. More specifically, the two U.S. researchers are investigating how our diet affects the behavior of the gut microbes and how this in turn influences our health. After all, what we eat nourishes not only us, but also the microbes inside our gut.

One of their research interests is therefore microbiota-accessible carbohydrates, known as MACs. They are what the gut microbes feed and thrive on. “The genomes of the bacteria living in our gut, which actually account for over 99 percent of our genetic material, are very good at degrading complex carbohydrates from vegetable matter,” Erica Sonnenburg explains. “They metabolize the MACs to produce many different types of small molecules. Some of these enter the bloodstream and can circulate all around the body.”

High-fiber and fermented foods

People wishing to do their gut microbiome a favor should eat foods containing large quantities of MACs. This includes high-fiber foods like beans, pulses, vegetables, fruit, wholegrain products, nuts and seeds. Erica Sonnenburg’s advice is to eat at least 50 grams or more of fiber every day. Fermented foods are also very beneficial for the microbiome, for instance yoghurt, kefir, sauerkraut, the conserved Korean cabbage kimchi, and kombucha, a fermented Asian tea.

But the problem is that many people in modern societies have a diet that is different – it contains little fiber and is not fermented. All too often it includes heavily processed foods like frozen pizza, sweet or salty snacks, cookies, chicken nuggets or instant soups. These foods contain a lot of sugar, fat and salt, along with emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners and other products of the modern food industry. The gut microbiome, however, cannot utilize these substances. “When that happens, it is forced to feed on the only other source of food that is available – the intestinal mucosa. So if we don’t eat any plants, the microbiome starts eating us.” The immune system then reacts and raises the alarm by triggering inflammation. It tries to prevent the gut microbes from getting too close to the human tissue that lines the gut and feasting on it. “This results in a real inflammation cascade. We think this is involved in a key way in the development of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular and auto immune diseases like Crohn’s disease, and also in the pathogenesis of some types of cancer in which inflammation plays the main role.”

However, a gut microbiome in poor condition can cause more kinds of problems. Our immune system has to function properly. It has the job of recognizing attacks and warding them off – the immune reaction. To do this, it must be able to distinguish genuine threats such as invading infectious pathogens from harmless things such as ingested food,” Justin Sonnenburg says. The gut microbiome helps to do this. It trains the immune system to make a clear distinction between friends and foes. Here, both sides – the immune system and the gut microbes – are in a sort of permanent “conversation.” They exchange information. If this conversation gets blocked, the consequences are far-reaching: “The immune system suddenly starts making mistakes. It thinks that something totally harmless, like a peanut or even the body’s own cells, is dangerous.” This mistake – that may be caused by a disrupted gut microbiome – can also make us sick and lead to the development of auto immune diseases or several other chronic diseases.

That is reason enough to keep the gut microbes supplied with plenty of MACs. But it’s not too late for a person who has been eating an unhealthy diet for a longer period and is already suffering from inflammation as a result. “We’ve discovered that changing one’s diet can have a lot of positive effects,” says Erica Sonnenburg. “Fermented foods like yoghurt and sauerkraut are really effective at least at alleviating inflammation that is already happening.” And there’s more: adapting the diet can also restore the diversity of a disrupted microbiome – which is a key health aspect because the greater the variety of microbes present in the gut, the better they can do their jobs collectively. And the fewer there are, the more easily we fall sick. For example, there’s a connection between reduced microbial diversity and obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Impoverished gut microbiome

A lot also depends on diet when it comes to microbial diversity. It turns out that not only industrially processed foods are bad for diversity, but so is taking antibiotics and – right at the beginning of our lives – consuming industrially produced baby formula. Which is why people in industrialized societies have only a few hundred different types of microbes in their gut. “This kind of gut microbiome appears quite impoverished when we compare it with that of people in non-industrialized hunter-gatherer societies, who have over a thousand different sorts of microbes in their gut as a result of their diet.”

Why is research into the interactions of microbes in the gut important? “Everyone knows that organs like the heart and liver are essential to life,” Justin Sonnenburg replies. “But the gut microbiome also belongs in this category because it exerts a huge influence on our health and well-being.” What are the scientific goals for the next few years? “We want to obtain a more precise understanding of how the gut microbiome works – from birth to adulthood – and to utilize this knowledge to develop better strategies and treatments for preventing and curing diseases. We’ve got our sights on the small molecules produced by the microbiome. Some of them could form the basis for future medicines used to treat a series of non-transmittable, chronic diseases.” As it takes several years to develop such medicines, it would be quicker to boost the gut microbiome – and with it our health – by altering our diet. “Everyone can start doing that right away.”

In November, Justin and Erica Sonnenburg will visit Frankfurt as the incumbents of the Friedrich Merz Visiting Fellowship. They will participate in a scientific congress at Goethe University, and there will be a public event as part of the Citizens’ University. This will include a showing of the film “Unser Bauch. Die wunderbare Welt des Mikrobioms” (“Our belly. The wonderful world of the microbiome”), which the couple worked on as consultants. During their stay in Frankfurt they want to talk with a large number of people, and not only with other microbiome researchers. Their work has always also been inspired by discussions with dieticians, doctors and engineers. The Sonnenburgs are looking forward to finding out more about the “great work” going on at Goethe University. And they would like to use the opportunity to pass on their knowledge about the gut microbiome to the people of Frankfurt.

Andreas Lorenz-Meyer

The Friedrich Merz Visiting Fellowship Endowment was founded in December 1985 on the 100th anniversary of the birth of company founder Friedrich Merz who, as one of the first members of the Senckenberg Society, was closely connected with Frankfurt University and who promoted science. The goal of the visiting fellowship endowment is to appoint particularly renowned scientists in the fields of pharmacy and medicine to Goethe University Frankfurt. Awarded the first time in 1987, the fellowship has since been awarded annually, with only two exceptions. Each year, the visiting fellowship and the symposium, whose topics range from fundamental research to health services research, provides scientists from universities and industry with an opportunity to exchange knowledge and further their collaborative work.

For more information on the dates of this year’s visiting fellowship, see p. 27 of this UniReport.

Friedrich Merz Visiting Fellowship 2024

Dietary and therapeutic microbiome modulation: State of the art and perspectives

Curator: Prof. Maria J. G. T. Vehreschild, Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases, Medical Clinic II, Frankfurt University Hospital

November 12, 2024

Students’ Lecture at Frankfurt University Hospital

10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., Frankfurt University Hospital

Erica and Justin Sonnenburg will give a lecture on “Industrialization of the Gut Microbiome and the Rise of Chronic Inflammatory Disease” for students and other interested persons, followed by time for questions.

November 13, 2024

Scientific symposium: Dietary and therapeutic Microbiome Modulation – State of the Art and Perspectives.

9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Frankfurt University Hospital, Building 6

November 14, 2024

Unser Bauch. Die wunderbare Welt des Mikrobioms (“Our belly. The wonderful world of the microbiome”)

6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m., Orfeos Erben movie theater, Hamburger Allee 45, Frankfurt am Main.

(ARTE France, 2019). Film + discussion with Prof. Justin and Dr. Erica Sonnenburg (Stanford University, U.S.) and Prof. Maria J.G.T. Vehreschild (Goethe University).

For more information and registration, see

https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/Friedrich-Merz-Stiftungsgastprofessur