On the trail of dark matter

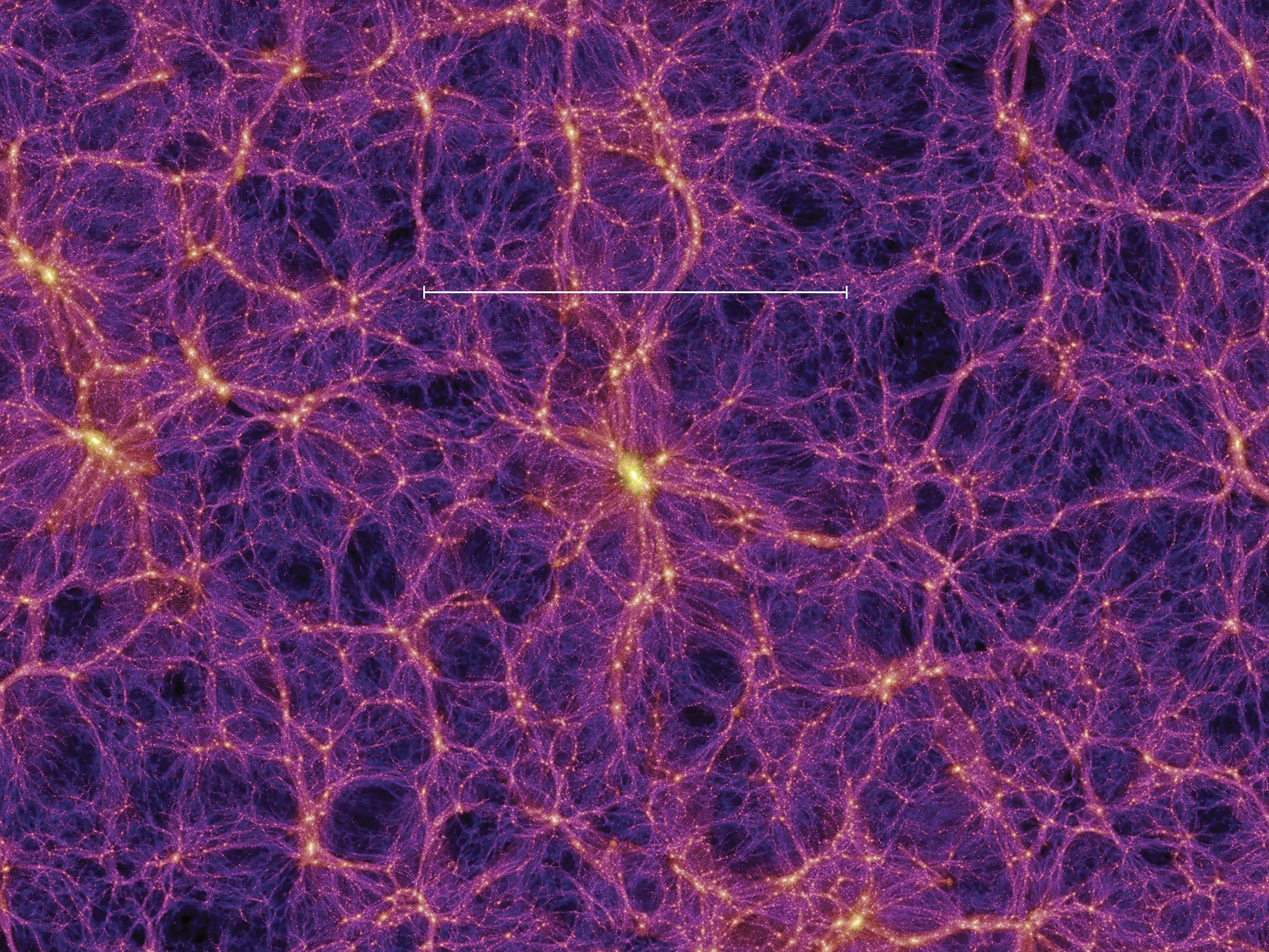

Dark matter in color: if it were visible, dark matter would spread in our Universe like this, as the Millennium Simulation Project shows.

Photo: Volker Springel, Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, et.al., Virgo Consortium

It’s a fact. Dark matter definitely exists. There is no longer any doubt about that. But what does it consist of? There are many conjectures. The possibility to measure gravitational waves has opened up an exciting new opportunity to study the particle properties of dark matter.

When, in the early 1930s, a Swiss astronomer suggested dark matter as an explanation for his mysterious observations, he was initially unable to assert himself in professional circles. Fritz Zwicky had noticed that the gravitational pull of the visible stars in the Milky Way and large galaxy clusters was not enough to hold the constellations together.

In the 1960s, astronomer Vera Rubin discovered that the orbital velocity of stars in galaxy clusters is much faster at the edges than it ought to be due to the gravity exerted by visible matter. Today, the existence of dark matter has been confirmed through the observation of other astrophysical phenomena. And, together with dark energy, it even constitutes the very largest part of the energy density of the Universe.

95 percent of the Universe is unknown

“We know this relatively precisely from observations of cosmic microwave background radiation and from the large-scale structure in the Universe: 95 percent of the Universe is unknown,” explains the physicist Laura Sagunski from the Institute for Theoretical Physics. “Dark matter is about five times more common than the visible matter that makes up stars and galaxies.” She says there is much to suggest that dark matter must have particle properties. This can be seen, for example, in the Bullet Cluster, a galaxy cluster in the Argo Navis constellation. Strictly speaking, it is two clusters, a larger one and a smaller one that passes through it like a bullet (hence the name).

What is interesting about this structure is that the luminous interstellar gas lags behind the mass distribution of the galaxy clusters, as images from the Hubble Space Telescope show. It is presumably dark matter that is behind this “clumping” at the center of galaxy clusters. “The two galaxy clusters passed through each other almost without colliding. We can explain this if we assume that dark matter has particle properties and that these particles pretty much don’t collide.” However, collisions between the two interstellar gas clouds do indeed occur that slow them down. That is why the gas lags behind the galaxies. Sagunski is interested in the following question: What are these particles of dark matter? They could, for example, be self-interacting dark matter, primordial – very old and light – black holes, MACHOs or axions.

MACHOs, WIMPs and other candidates

The abbreviation MACHO stands for “massive, astrophysical, compact halo object” and refers to the observation that the enormous gravitational field of these objects bends spacetime in such a way that it produces a gravitational lens for the starlight. This starlight is focused like through a lens so that the star temporarily shines brighter when it is near a MACHO.

However, it might also be the case that there is dark matter inside neutron stars, or that there are compact stars consisting entirely of dark matter. Sagunski is exploring this question with her group in the ELEMENTS research cluster and within the Collaborative Research Center “Strong-Interaction Matter under Extreme Conditions”. In this cluster, in which apart from Goethe University Frankfurt the universities in Giessen and Darmstadt as well as the GSI Helmholtz Center in Darmstadt are participating, researchers are agglomerating knowledge from nuclear, particle and astrophysics. Among other things, the question is how neutron stars are structured.

“As yet, we don’t know a lot about the particle properties of dark matter, especially in relation to its mass. The lightest would be the axions, hypothetical elementary particles that were introduced to expand the Standard Model of Particle Physics. Then would come the WIMPs and then the primordial black holes,” she says. WIMP stands for “weakly interacting massive particle”. But “wimp” is, of course, also a play on words that highlights the difference to “machos”.

If the mass of dark matter is large enough and if its motion alters, the changes in spacetime ought to be measurable as gravitational waves even here on Earth. This is because gravitational waves always occur when masses are accelerated, in a similar way to the electromagnetic waves emitted by accelerating charges in an antenna. Gravitational waves, however, are very much weaker, which is why they can only be measured at all in very massive astrophysical objects: in merging black holes, for example, or neutron stars that orbit each other.

Signals from black holes and neutron stars

In 2015 and with the help of the LIGO detectors in the US, scientists managed for the first time to directly measure the gravitational waves predicted by Einstein back in 1916. They originated from two merging black holes. Two years later, another spectacular direct measurement of gravitational waves conducted with the help of the LIGO and Virgo detectors was announced, which were the result of the collision of two neutron stars. Laura Sagunski can clearly remember it: “It was the day I gave a lecture on precisely that topic at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching.”

For theorist Sagunski and her colleagues, this has paved the way for revolutionary new research because they can use experimental data from gravitational waves for the first time to search for new physical phenomena issuing from previously unknown dark matter particles. Although it is not yet known what dark matter is really composed of, Laura Sagunski has clear favorites and talks about the various candidates for dark matter as if they were close acquaintances. One of her favorites is axions. Within the ELEMENTS research cluster, Sagunski has used the LIGO data to study for the first time the particle properties of axions, such as mass and decay constant.

The Bullet Cluster consists of two groups of galaxies, known as galaxy clusters (blue and red background, respectively). The smaller galaxy cluster (right) passed through the larger one from right to left. The gas (red) that surrounds them constitutes the largest mass of the galaxy clusters. The collision slowed it down, while the galaxies came away unscathed because they are a long distance apart. The galaxy clusters’ mass can also be calculated from the deflection of the light from light sources behind them. This effect is known as gravitational lensing (see diagram on p. 15) and shows that the clusters’ mass is mainly distributed around the galaxies (blue) and not in the visible gas: an effect of invisible dark matter. Photo: X-ray: NASA/CXC/CfA/M.Markevitch et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI;

Fascinated by dark photons

So far, we know that the particles of dark matter interact with each other via gravity. It is possible, however, that they might also do this via new, as yet unknown forces. “You would need a further exchange particle for this, which we call a dark photon, analogously to the photons in electromagnetic interaction,” says Sagunski. This, too, she adds, is only a hypothesis at the present time, but you can sense Sagunski’s fascination for these “really exciting” objects. After all, the dark photon hypothesis allows predictions about the interactions of dark matter. It might be the case, for example, that dark matter is not collisionless, as is commonly assumed, but instead that dark matter particles can self-interact with each other. A dark photon as an exchange particle can mediate this self-interaction.

“Personally, I’m a great fan of self-interacting dark matter because, for example, with that we can explain the rotation curves of dwarf galaxies much better,” says Sagunski. These rotation curves describe the orbital velocity of stars depending on their distance from the center of the galaxy. There are often discrepancies between the observed and the calculated curves, as Vera Rubin already noticed in the 1960s. In dwarf galaxies, self-interacting dark matter can explain these discrepancies better than collisionless dark matter.

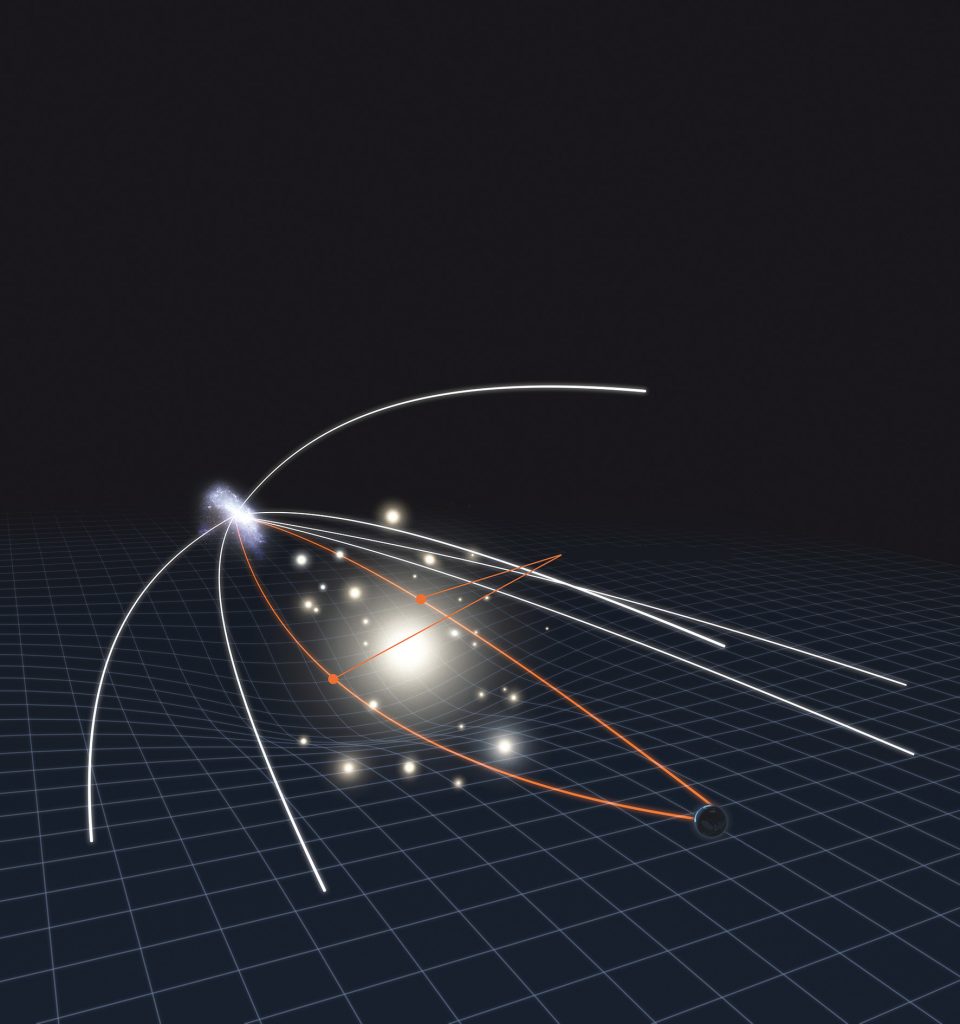

To study self-interacting dark matter with gravitational waves, Sagunski uses supermassive black holes that are between a thousand and a million times heavier than the Sun. Their gravitational pull is so strong that enormous dark matter halos ought to form around them. However, unlike the rings of light that surround celestial bodies like a halo, they would be invisible.

Compact, smaller objects such as black holes or neutron stars orbiting the black hole lose energy in the process. And the denser the dark matter halo, the more energy is lost. “We have recently pondered whether we can draw conclusions on the density profile and particle properties of dark matter from the gravitational waves transmitted by such a system. And that is indeed possible,” Sagunski explains.

“We” is her group, consisting of one postdoctoral researcher and four doctoral candidates, four Master’s students and four Bachelor’s students. Teamwork is important to her: “I draw a lot of my energy from working with the fantastic people around me,” she says. And she cherishes an environment where women and men from a wide variety of backgrounds and with different expertise come together. “That’s one of the major strengths of ELEMENTS and also what makes the projects special for me.”

Looking ahead

The experimental data that Sagunski wants to use to test her group’s latest calculations will be a little more time in coming. LISA, the proposed Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, is expected to deliver them in the mid-2030s. The experiment, planned jointly by ESA and NASA, the European and American space agencies, consists of three satellites arranged in the shape of a triangle – with an edge length of 2.5 million kilometers! Like LIGO/Virgo, the experiment will measure gravitational waves. While the LIGO/Virgo detectors measure signals from merging neutron stars or black holes at relatively large frequencies, the LISA detector, by contrast, will be able to measure signals at smaller frequencies thanks to its size, for instance those from supermassive black holes orbited by compact objects. This means that LISA holds a lot of potential for exciting new discoveries.

For the time being, however, there are enough other dark matter mysteries on the frontiers between particle physics, cosmology and gravitational wave physics that Laura Sagunski and her team can explore. One of these is the possibility to explain the effects for which dark matter is now being held responsible in a completely different way. Namely, by arguing that Einstein’s general theory of relativity needs to be further extended or modified. Sagunski and her team can do a reality check for this possibility by comparing it with data from gravitational waves. “The theories worth considering are meanwhile extremely limited, but we definitely cannot rule out the possibility,” she explains.

Professor Laura Sagunski earned her doctoral degree at the University of Hamburg and the DESY research center, also in Hamburg. From 2016 to 2019, she was a postdoctoral researcher at York University in Toronto and at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada. After a year at RWTH Aachen University, she accepted a professorship in Theoretical Gravitational Wave Physics at Goethe University Frankfurt in 2020. She is a Principal Investigator in the ELEMENTS research cluster and the Collaborative Research Center “Strong-Interaction Matter under Extreme Conditions”. In 2022, she organized the online conference “Women in the World of Physics”, which over 950 female physicists from throughout the world attended.

The author: Dr Anne Hardy, born in 1965, graduated in physics and holds a doctoral degree in the history of medicine and technology. She works as a freelance journalist in Frankfurt.