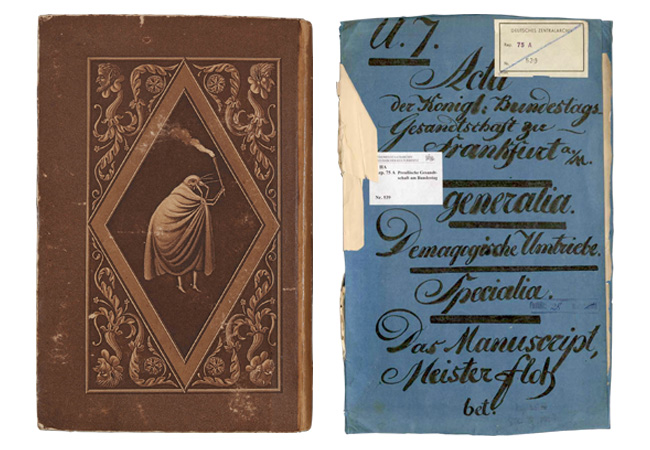

Dark Matter (2003) by Eva Grubinger

Dark Matter was an installation originally created for the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead (UK), which opened in 2002 and was built as part of the town’s post-industrial redevelopment; the town and region in North East England were long dominated by coal mining and trading before more and more service providers, such as call centers, settled there. The sound collage was composed by Curd Duca. In 2007, the installation could be viewed at Eva Grubinger’s solo exhibition, “Spartacus”, at the SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT art gallery.

Already from a distance they appear strange. Foreign and familiar, repellent and compelling at the same time. As we enter their circle, we are uncertain whether the intention is to exclude, include or suck us in. Dark matter must be taken quite literally here: jet-black corpuses made of an unknown material that could equally be extremely heavy or light as a feather. Opaque surfaces that absorb all light and black mirrors that reflect every glance back at themselves.

At first, we feel invited to wander curiously around the free-standing objects and explore them. Because of their size, they confront us almost at eye level – most of them, however, tower above even the tallest among us, obliging us to look up at them. What’s more, no matter how close we get to them, they reveal almost nothing of themselves. They are vaguely reminiscent of architectures and things we know from everyday life. A tower block. A cooling tower. A control tower. An enormous headset. Two other elements are more self-effacing, as it were: a partial sphere whose shape might remind us of a reactor dome. And on the back wall of the room, rectangular panels that look like sealed up windows.

They all contribute, each in their own way, to a sense of unease that grows and grows the longer we linger in their circle. This might seem the least surprising in the case of the control tower – like in the original, mirrored windows in the model, too, support a one-way regime that leaves us uncertain whether we are being watched right now or not. Looking inside the cooling tower via the likewise reflecting baseplate, whose functional architecture turns out to be an empty shell, is no less uncanny, while the reactor hums menacingly behind us. Or are we just imagining it?

In the case of the tower block, in turn, it is not only the blind rows of windows in the monotonous façade, at the foot of which we search in vain for an entrance; what appears to be an opening – at least from a distance – also has disappointment in store: the horizontally offset part of the upper floors rests on the lower ones on steep stilts alone; it seems that no provision has been made for a transition between the two zones.

When we finally step into the semicircle of the headset, the discomfort becomes physically tangible: deep vibrations from within the gigantic headphones, sound waves somewhere between whirring, whispering and buzzing, which disappear again in the same moment, scarcely have we asked ourselves if we have heard them at all, and which, incidentally, reverberate more in our guts than in our ears, making us vibrate as well.

Dark matter: although invisible to us, we can assume that it not only exists, but is also of existential importance for our Universe. We still lack the instruments to grasp its structure and its forces – which we should not, however, ever tire of investigating. After all, it’s about the world in which we live.

Although the objects and architectures in whose maelstrom we are caught up here are nothing but images, and the systems they represent are of comparatively modest dimensions, it is scarcely a coincidence that the row of black mirrors on the back wall casts these images into the room, back at us, and ensures that we merge into one with them.

Unlike that in the Universe, this dark matter is made by humans for humans. This applies both to the jet-black objects as well as to those existing in reality, sometimes almost equally sealed off, for us largely inaccessible apparatuses and systems to which they relate. They are uncanny to us because we know too little about them and at the same time feel that they hold a power over us. Because we believe that we are outside them, whereas we are, in fact, part of them.

The systems that we design and construct, with and in which we create our worlds, work and live, are indeed small universes. And that is precisely why we should want to know how they work. To be able to act responsibly and effectively within them, we need to understand them.

About

Eva Grubinger, born in 1970 in Salzburg, lives and works in Berlin. Her works are shown at international exhibitions and found in both public and private collections. She has been awarded numerous scholarships and prizes. Between 2008 and 2018, she also taught as a professor or visiting professor at the art academies in Linz, Düsseldorf and Munich.

Die Autorin:

Verena Kuni is Professor for Visual Culture at the Institute of Art Education.