The urgent need for conservatives in Europe’s party systems

by Thomas Biebricher

Maxime Tschanturia/Shutterstock

Les Républicains in France, the Tories in the UK, the Christian Democrats in Austria: Parties that for decades were considered an established political factor in their countries have seen a rapid loss of importance, with some shifting towards the far right. However, for a stable democracy ready to embrace whatever the future might hold, a moderate conservative force to the right of center is essential.

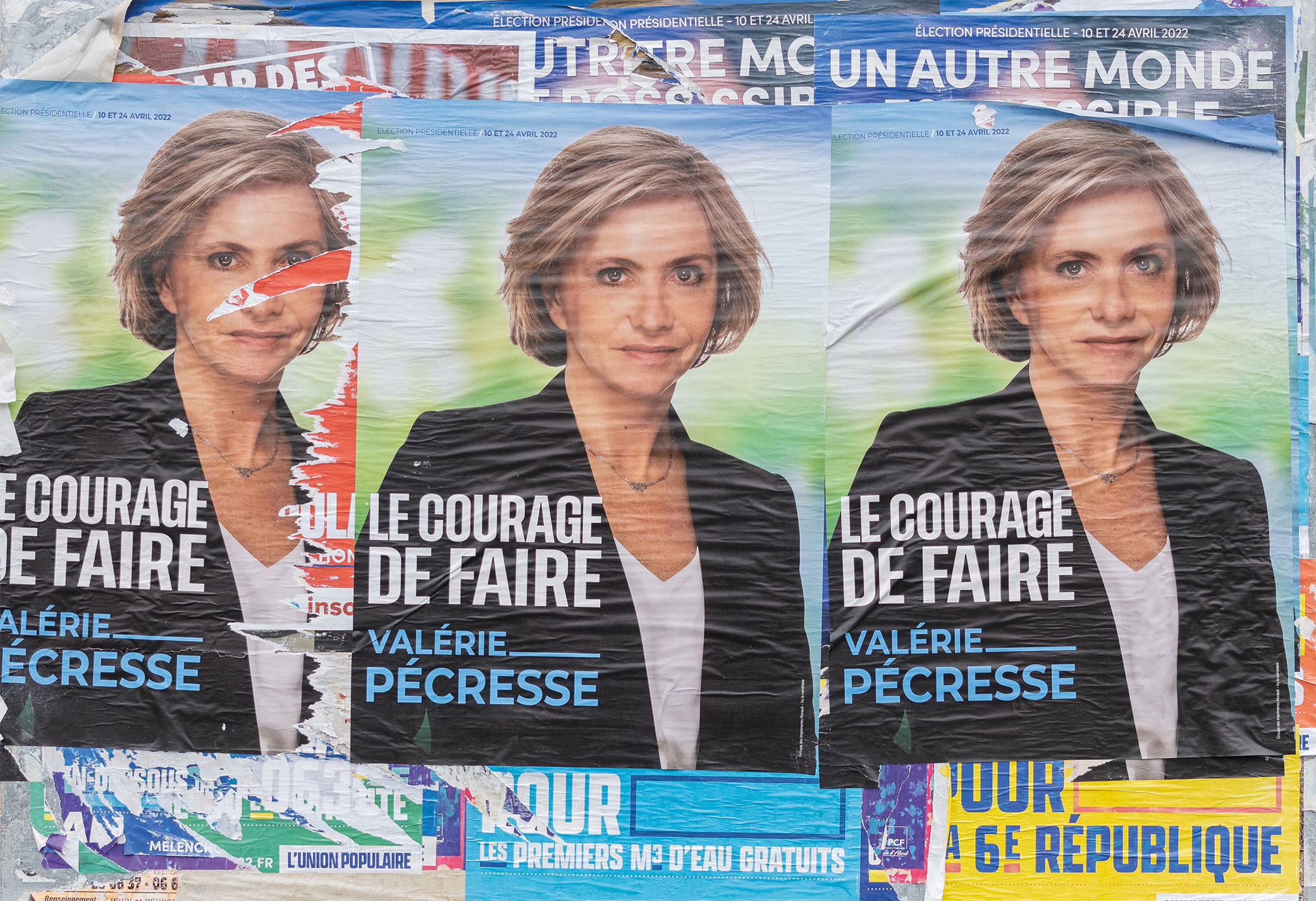

When Valérie Pécresse, the candidate of the center-right party Les Républicains, stepped out before the press after the first round of the French presidential election in 2022, she not only had to concede defeat. Worse still, Pécresse had not even secured five percent of the vote and would therefore not benefit from state reimbursement of her election campaign costs. As a result, she had to ask the party base for donations in front of the rolling cameras, as the party and she herself had taken out loans to finance the campaign.

It was the lowest point so far in the already dramatic decline of a former people’s party, which in its earlier incarnations as the party of de Gaulle, Pompidou and Chirac had shaped the fortunes of the Fifth Republic like no other and was now fighting for political survival. A fall from grace that is to some extent symptomatic of a trend that can be observed in almost all of Europe: Order in the party systems is visibly eroding. Having said that, we must undoubtedly be careful when talking about the order of party systems, which have grown historically and sometimes developed differently due to the partly very different lines of social conflict and electoral systems. Nevertheless, one of the “elements of order” of almost all European party systems that (re)formed after the Second World War was that their center-right was typically occupied by moderate conservatives, which also included Christian democratic parties. And in this sense, it can indeed be said that the order of party systems as we knew them in Europe has been well and truly thrown into disorder in the recent past.

From people’s party to niche existence

The demise of the Republicans in France is only the latest and most dramatic testament to the wide-scale weakening of moderate conservative parties, the outcome of which is not least that the center-right is becoming increasingly empty. However, before we discuss the consequences of this development for liberal democracy, it is worth looking at the different patterns manifested by the crisis of European conservatism.

The most obvious phenomenon is, of course, the waning to niche existences of the formerly proud people’s parties of the center-right. The demise of the Republicans in France, who celebrated a magnificent election victory with Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007 but then failed to enter the second round of the presidential election exactly ten years later with their candidate François Fillon, is a striking example, of course, but it is not the only such case. In Italy, after the implosion of Democrazia Cristiana (CD), the Christian democratic party, in the 1990s, the center-right was soonest represented by Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (FI), apart from a few post-Christian democratic splinter parties. However, at the latest since his death, it cannot be ruled out that the party will now fade into political insignificance, given the extreme personalization of the FI, which centered entirely on its founder. Both cases show that the weakening of the center-right parties has led to the center of gravity shifting from center-right to far right: In Italy, Fratelli d’Italia and Lega are setting the tone, in France it is Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National.

Radicalization in the face of competition

The second pattern is the self-radicalization of formerly more or less moderate conservative parties. In Central and Eastern Europe, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz and the PiS under the (indirect) leadership of Jarosław Kaczynski are the most important instances. The most spectacular example of this self-radicalization in the Western European context is the Tories in the UK, who drifted further and further away from the political center in the course of the Brexit battles and in the face of right-wing competition from Nigel Farage’s UKIP and, under Boris Johnson’s leadership at the latest, not only mutated into the – for all intents and purposes – real Brexit Party, but also became confusingly similar to UKIP in terms of their political style, culture wars and anti-migration issues. At first glance, this repositioning was even crowned with success: The Conservative Party ousted UKIP by becoming UKIP itself, as it were. In 2019, Johnson secured a majority for the Tories that had not been seen since the time of Margaret Thatcher. However, to achieve this it was necessary to surrender the center-right, and the radicalization process brought with it hefty conflicts within the party and a partly chaotic cabinet: As a result, the Conservative Party can be expected to emerge as the loser from the next general election.

Finally, there is also a transnational phenomenon that is likewise indicative of both a weakening and a drift to the right of the center-right camp and which consists in moderate conservative parties relying on the support of partly right-wing extremist forces to form governments and showing that they are willing to accept this support from the far right. This is the case in both Sweden and Finland, where the Sweden Democrats and the Finns Party, respectively, co-determine the government’s destiny. When center-right parties succumb to such collaboration, they naturally also have to offer the right-wing authoritarian forces something in return for their support, which, however, invariably causes the policies of such allegedly “center-right coalitions” to shift to the right. In Sweden, the country’s migration regime was immediately toughened, and the government itself speaks of a “paradigm shift”, which includes the forced deportation of rejected asylum seekers and a harsher response to supposed “asylum fraud” as well as stricter requirements for acquiring Swedish citizenship.

IN A NUTSHELL

• Order in Europe’s party systems has been thrown out of sync: Formerly proud conservative people’s parties are fading into insignificance or shifting towards the far right.

• In France and Italy, for example, the weakening of the center-right parties has led to the center of gravity shifting from center-right to far right.

• A different pattern is manifesting itself in Central and Eastern Europe and in the UK: the self-radicalization of formerly moderate conservative parties.

• To ensure their political survival, moderate conservative parties are increasingly prepared to take on government responsibility with the support of partly right-wing extremist forces.

• Liberal democracies depend on the presence of stable and active center-right parties because these are particularly capable of supporting processes of social change and of steering the political dynamics released within them along constructive paths.

Importance of conservative parties for social transformation

Overall, the European panorama thus presents a rather worrying picture, and not only from a moderate conservative perspective. After all, liberal democracies rely to a certain extent on the presence of stable and active center-right parties. These are particularly capable of harnessing processes of social change and the political dynamics released within them and of steering them along reasonably constructive paths. Conservative parties co-decide whether changes appear in the first instance as threats that provoke a fear of loss, on which the right-wing authoritarian forces in many respects base their business model, or whether this fear can be tackled by society in a more productive way by mediating and campaigning for acceptance – also and especially in milieus that are simply not (or no longer) amenable to the Greens and left-liberal forces, for example.

CDU/CSU in the post-Merkel era

Against this backdrop, we must ask ourselves whether the CDU/CSU is still willing and able to occupy the center-right and engage in corresponding politics or whether it is drifting – like it or not – to the right. The rise of the Alternative for Germany party (AfD) as well as the inter- and intra-party squabbles and fighting in the post-Merkel era suggest that this question is by no means trivial. That there are two opposing camps within the CDU is crystallizing more and more. One is represented by party leader Merz and General Secretary Linnemann, who believe that the CDU/CSU needs a clearer conservative and more liberal profile and must not shy away from the culture war debate. The second camp, which leans more towards the political center,

is represented above all by minister-presidents Wüst and Günther and warns that this course is increasingly calling into question the party’s demarcation from the AfD and that it needs to keep an eye on the centrist milieus which have voted for the CDU/CSU in the past, primarily because of Merkel’s ultra-pragmatic course. Whether it will be possible to find a balance between the two camps or whether one of the two will assert itself, and what consequences this will have for the internal stability of the CDU and the CDU/CSU as a whole, can presumably only be answered after the European and regional elections. For the time being, the CDU/CSU seems to have decided on the rudimentary strategy of keeping a maximum distance from the Greens and of attacking them as the party of prohibition and paternalism – also because adopting this course is most likely to play into the hands of the party’s regional branches in the federal states of eastern Germany that have to contest an election in 2024 (Thuringia, Saxony, Brandenburg), where the Greens play practically no role at all and the CDU finds itself confronted at eye level above all with the AfD. Once the governments in Erfurt, Dresden and Potsdam are in place, the first step will be to take stock. Strategic and personnel consequences will then follow.

The author

Professor Thomas Biebricher, born in 1974, has been Heisenberg Professor for Political Theory, History of Ideas and Economic Theories since 2022. After studying and completing his doctoral degree in political science in Freiburg, Germany, he spent six years as a guest lecturer of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) at the University of Florida before taking up a position as a junior research group leader at the Cluster of Excellence “The Formation of Normative Orders” in Frankfurt in 2009.

After several deputy professorships at Goethe University Frankfurt and a research stay at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, he was appointed as Associate Professor at Copenhagen Business School in 2020. His research interests lie in critical theories, the analysis of neoliberalism in theory and practice, and the crisis of conservatism.

biebricher@soz.uni-frankfurt.de