“The Future of Democracy” was the annual theme of the 2024/25 Wisser Fellowships. Political scientists and postdocs Selma Kropp and Luca Hemmerich pursued their research within Normative Orders with great enthusiasm.

“Children’s Rights in the Context of Migration: Navigating the Regime Complex between Strasbourg, Brussels, and Geneva” is the research project of young political scientist Dr. Selma Kropp. With her Wisser Fellowship, she has taken up two thematic strands from her earlier research: the work of bureaucrats in international organizations, and children’s rights. “I came to the topic of children’s rights during my studies, through an internship at the German Permanent Mission to the United Nations. I had the opportunity to follow and report on debates in the UN Security Council concerning children’s rights issues. Since then, my research has focused on this area. In my master’s thesis, I examined which violations of children’s rights are highlighted within the United Nations and which receive less attention. In my doctoral dissertation, I shifted my focus to the regional level, asking: How did the process unfold from the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child to its formal institutionalization at the regional level? After finishing my PhD, I had the idea to examine one particular aspect in more detail: the detention of children in the context of migration. This issue is highly visible in regional European organizations, but also highly contentious. The crucial question is: What opportunities do bureaucrats have to keep contentious issues like this on the agenda, even against the interests of certain member states?”

In her research project, Kropp identified two mechanisms: For one, bureaucrats exploit overlaps in competences and memberships between organizations, including between the Council of Europe and the European Commission. “They more or less pass the ball back and forth – in designing projects, issuing communications, or at conferences,” she explains. A second option is to shift contentious topics to other forums. Roughly every ten years, for example, the UN publishes a study on the implementation of children’s rights. Bureaucrats from European regional organizations also contribute to these UN studies. “The most recent study, from 2019, makes it clear: In the context of migration, deprivation of liberty cannot be reconciled with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. According to the Convention, deprivation of liberty should be used only as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time. That is hardly the case in migration contexts.” How does Selma Kropp proceed methodologically? In the ongoing project, interviews with bureaucrats from governmental and non-governmental organizations are the main source of material. “I start by posing open questions, because I want to establish rapport with the bureaucrats and understand their work.” The interviews are then analyzed and checked for recurring themes. “The research direction I pursue examines the extent to which overlaps between organizations can influence political processes.” This critical perspective, she explains, stems from critical norms research. “With children’s rights, it’s easy to observe that actors initially see them positively, but the more one gets into the details, the more complicated matters become. Contestation over the details of implementation is therefore unsurprising.” Commenting on current developments, the political scientist testifies that frustration over the fact that some member states are fundamentally questioning human rights was palpable in many interviews. “If the very idea that people have fundamental rights is called into question, the discourse is moving in a troubling direction.”

Her colleague Luca Hemmerich is also a political scientist, focusing on a highly topical issue: the ecological crisis of our time, and more specifically, the ecological expansion of democracy. Ecological issues have concerned him from an early age, he says. “As a teenager, I was active for several years in the climate movement. In my research, I engaged with political theory; in my dissertation, I investigated the concept of interest. As part of my postdoc project within the Wisser Fellowship, I wanted to address a different topic – and, in a sense, I have returned to the ecological question.” Hemmerich examines what political institutions could look like that integrate “voiceless” groups still excluded from democratic decision-making. “Future generations – children, but above all those yet unborn – and non-human animals will be most affected by the ecological crisis. Yet their voices are not heard; democracy is incomplete in this respect. But we need democratic institutions to tackle the ecological crisis. The claim that only some kind of ‘eco-dictatorship’ could bring about rapid policy change is, in my view, completely wrong.” The key question Hemmerich examines is that of representation. How can non-human animals, who cannot participate in parliamentary debates, be represented at all? Hemmerich explains that he uses the somewhat unwieldy term “non-human animals” to underline that humans are also animals, and to emphasize a certain conceptual continuity.

He continues: “There are theories that seek to develop another form of representation beyond the traditional understanding of the term. They posit that democratic representation is not simply a mirror of those being represented, but more about acting on someone’s behalf. Concepts such as ‘proxy representation’ are intended to capture the idea that ‘voiceless’ groups must have representatives who bring certain concerns into discussion and decision-making processes, even though they cannot be held accountable by those they represent.” Does our democracy lack future orientation – is it too focused on the present? “Yes, perspectives are heavily focused on the present and on humans. Animals and ecosystems are not included. At best, they appear in instrumental terms, in terms of their usefulness to humans. A deficit in many ecological debates is that, while there is much discussion of specific measures – such as phasing out combustion engines, introducing a CO2 tax, or feed-in tariffs – there is no discussion of why we are repeatedly confronted with ecological problems. This lies in the basic structure of our democratic institutions. How these can be changed, beyond individual measures, must be explored.” As a political theorist, Hemmerich works primarily with systematic-philosophical argumentation but always draws on empirical studies. His aim is to question the basic concepts of the political landscape: What does democracy mean? What does representation mean? “To sum up my thesis once more: The ecological crisis is not only the result of the failure of specific measures but is embedded in the basic structure of our democratic institutions.”

Having reached the end of their Wisser Fellowships, both early career researchers rave about the optimal working conditions at Normative Orders. “There are so many researchers in the field of International Relations – it was a very fruitful exchange for my work,” emphasizes Selma Kropp. Luca Hemmerich adds: “The research strength that exists here in the field of political theory is probably unique in Germany. I am very pleased to be part of this research community.”

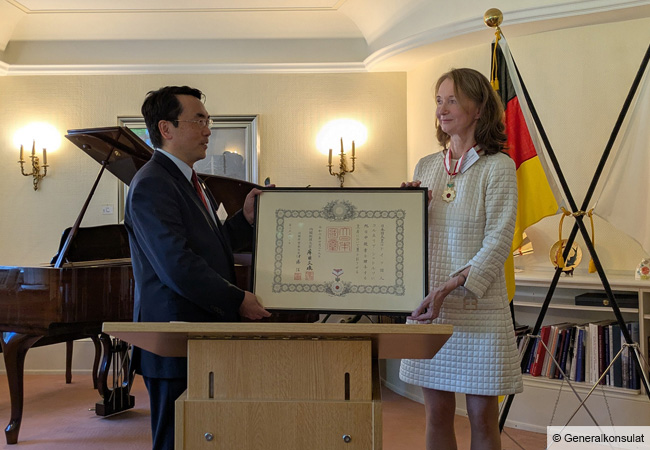

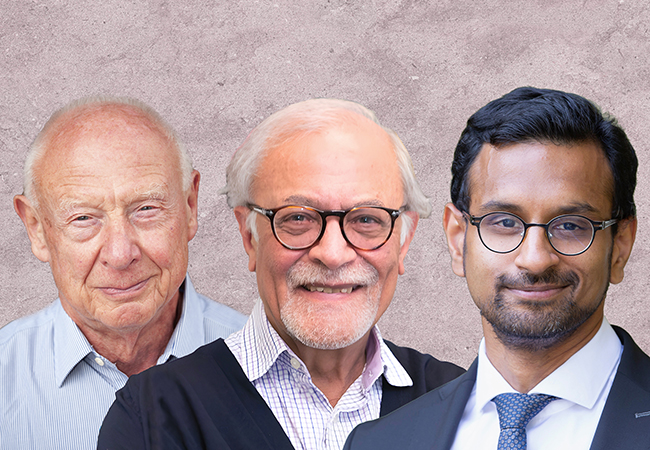

Professor Rainer Forst, who co-founded and co-directs the program with Prof Nicole Deitelhoff, is enthusiastic about the work of the two postdocs. “We thought it a very fitting tribute to the memory of Claus Wisser to realize such a program with young, outstanding minds like Selma Kropp and Luca Hemmerich. This is where the key to scientific progress lies. The great international response to our calls for applications is proof of this.”

The Claus Wisser Fellowships at Normative Orders, funded by a generous donation from the late Claus Wisser and carried out in cooperation with the Pro Universitate foundation, bring two outstanding postdoctoral researchers to Frankfurt each year to work on key questions concerning the transformation of normative orders. A new theme is chosen each year. The program is coordinated by Prof. Rainer Forst and Prof. Nicole Deitelhoff.