High tech and artificial intelligence shed light on the cellular nanocosmos

by Andreas Lorenz-Meyer

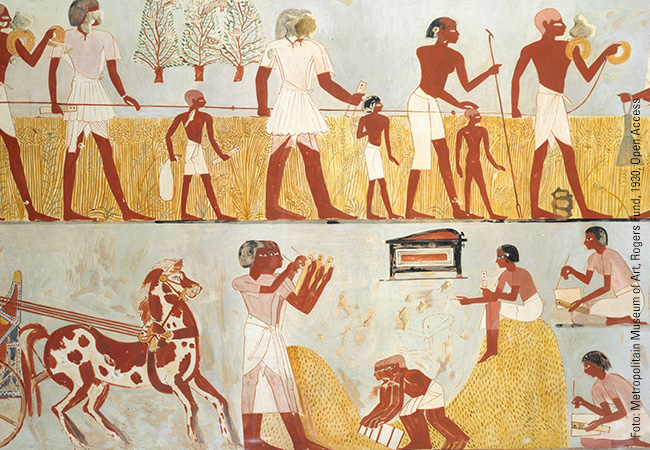

Photo: Heilemann WG

To advance biomedical research, chemist Mike Heilemann wants to better understand processes in human cells. To achieve this, he is using super-resolution microscopy and making the invisible visible.

In 1873, Ernst Abbe, a physicist from Jena, described the following phenomenon: If the distance between two structures is less than about half the wavelength of the light used to observe them, they no longer appear as two spatially separate objects under the microscope. For visible light, this optical resolution is in the range of 200 to 300 nanometers, which causes structures in close proximity to blur, making them indistinguishable. For cell biology, this is detrimental: A small protein is only a few nanometers in size, and in the cellular context is separated from its neighbors by much less than these 200 nanometers. This means that the optical visualization of densely packed proteins in cells is not possible with diffraction-limited imaging technologies. Fortunately, however, it is possible to circumvent Abbe’s resolution limit thanks to sophisticated light microscopy techniques, which are subsumed under the term “super-resolution microscopy”. Mike Heilemann from the Institute of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry is conducting research in precisely this area. Step by step, he is making more and more tiny objects and even spatial arrangements in the cellular nanocosmos visible

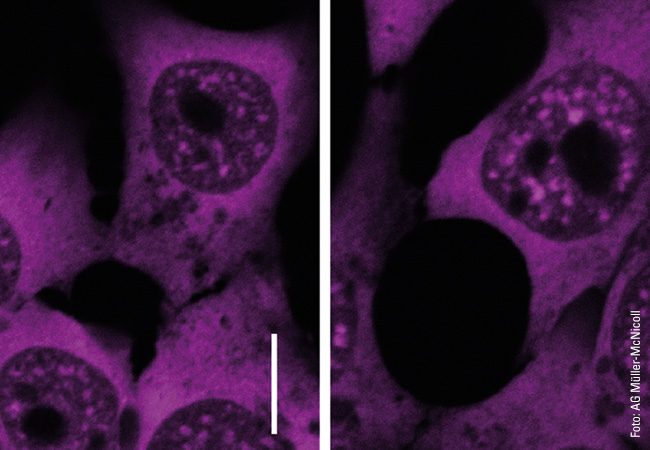

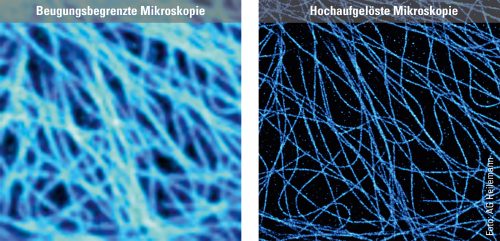

To illustrate the capabilities of super-resolution microscopy, Heilemann presents two images side by side on the computer screen in his office. They both show microtubules, rod-shaped protein structures that form something like tracks (known as filaments) in the cell to transport substances from one place to another. For the microscopic images, the filaments were stained with a fluorescent dye that emits light when exposed to laser illumination. The first image shows the limits of conventional technology: The microtubules appear blurred. The filaments, bluish shimmering threads, are so fuzzy that in some cases it is impossible to distinguish between them. “What we are seeing here is diffraction,” explains Heilemann. “This causes fluorescent dyes of one to two nanometers in size to appear as a much larger, circular light pattern, 200 nanometers in size. The thinnest tubulin filaments, which are actually only 25 nanometers in diameter, in consequence appear large.” The second image, which was produced using super-resolution microscopy, looks different. Here, the light probes do not produce any “fuzzy effect”: The filaments appear much sharper, and it is possible to distinguish between them in the image. In this way, the spatial structure, the tangle of individual filaments snaking over and under each other, becomes visible.

Many images one after the other

An important technology in the field of super-resolution microscopy is single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), a special fluorescence microscopy technique. Essentially, fluorescence microscopy uses dye molecules that are excited by light and themselves emit light of a different wavelength (fluorescence). The dye is attached to a biomolecule (e.g. an antibody), and both are directed together as a fluorescent probe towards the target molecule in the cell, where the probe docks. If laser light of certain wavelengths is then cast on it, it emits flashes of light, which make the target molecule, such as a protein, visible under the microscope. The trick with SMLM is that the probes do not emit the flashes of light simultaneously, but one after the other. One target molecule lights up, then the next. “This temporal separation makes it possible to isolate single fluorophores, determine their precise position and reconstruct images that have an almost molecular resolution of a few nanometers,” says Heilemann.

However, single-molecule localization microscopy has a major disadvantage: It is slow. Heilemann explains: “Let’s assume that there are 100,000 copies of our target protein in a single cell. To show this, we have to optically separate 100,000 individual dots. Only a few molecules can be detected simultaneously per image, otherwise the fluorescence signal will overlap.” The image would then only show something indistinct and indefinable and not the molecular structure. But just a few molecules per image means that many individual images are required for 100,000 dots – a time-consuming endeavor.

Artificial intelligence helps

Heilemann has succeeded in speeding up the process considerably. As a basic technique, he uses a specific SMLM approach called the PAINT technique. Here, the fluorescent probes dock onto the target molecule only briefly, emit their light signal and then disappear again. The increase in speed is thanks to neural networks (deep learning) that were added as a “digital extension” to the microscope. This artificial intelligence can be trained to recognize molecules and determine their position, even if the distance between the molecules is much smaller than the resolution limit. “This enables us to process a much larger number of molecules per image,” explains Heilemann. Imaging is 10 to 20 times faster, and only a few individual images are required for the whole structure.

For Heilemann and his team, however, the scientific knowledge they have gained from working with the neural networks is even more important than the time saved because it is only by increasing the speed that dynamics in the living cell, the movements and changes, can be visualized. A high-resolution video of a living cell that Heilemann shows on his computer clearly illustrates this: An organelle in the cytoplasm, the endoplasmic reticulum, can be seen. It consists of membranes that form many tubes and sheets that dynamically change their organization.

In the video, the tubes can be recognized as thin, white lines that are constantly moving. They separate from each other and then join up again. The structure changes shape each second. This is how it looks when the organelle’s tubes rearrange themselves. This process takes place constantly over a cell’s lifetime and has to do with the tasks of the endoplasmic reticulum, which is responsible for sub-steps in protein synthesis, as well as for protein degradation. “We don’t yet understand a lot of what is happening there, as our imaging has only recently progressed into this area. We can currently achieve a resolution of 30 to 40 nanometers – which is a very good result for structural imaging in living cells. The critical factor here is that we use renewable fluorescent probes so that we can observe these dynamics in living cells over a long period.”

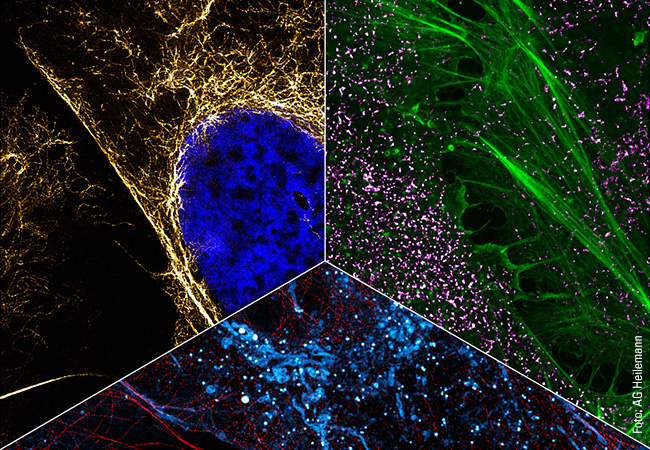

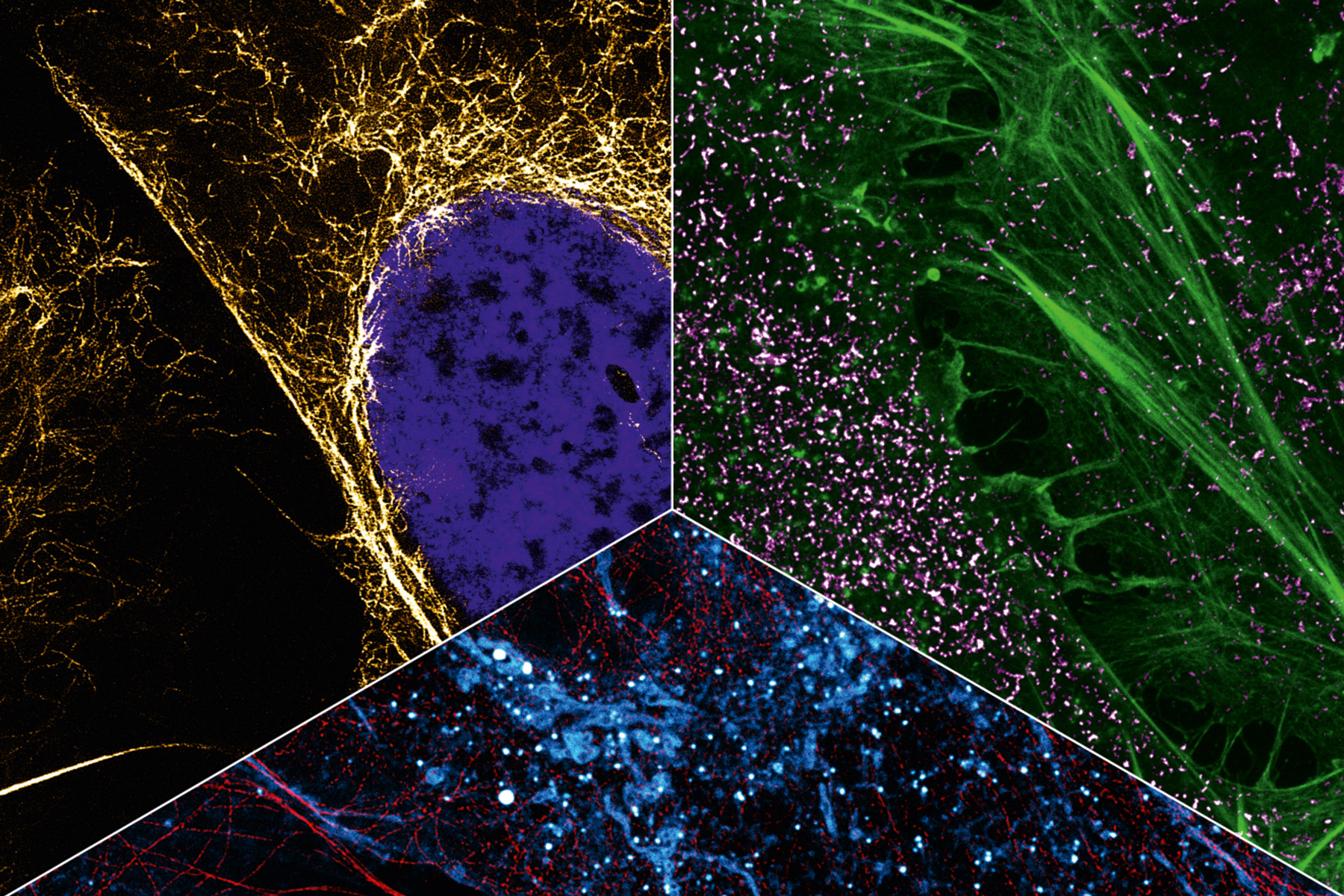

Adding different colors

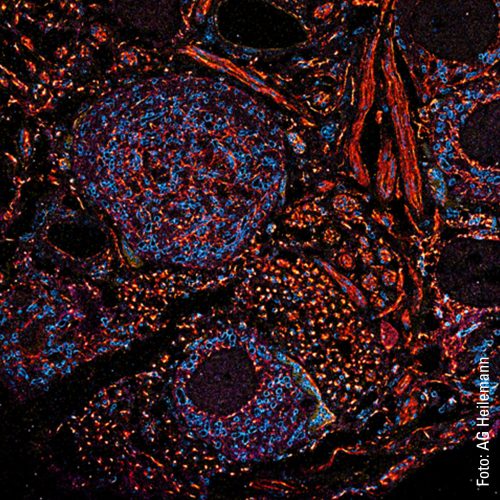

In addition to capturing the dynamics in the cell, another aspect of Heilemann’s work is concerned with the ability to capture the cellular context by tracing several targets in the same cell. This requires colors, as many colors as possible. Heilemann: “In each cell, there are thousands of different proteins with different functions. It is not enough to look at one or two of them because we want to understand the ‘molecular sociology’, the interaction of the individual proteins and protein complexes. Like us humans, at the end of the day these are merely the result of their environment. And to decipher the structural organization of the cell, we have to map this environment as a whole.” To achieve this, Heilemann and his research team are again using the PAINT technique, which brings the target molecule and the light probe together for just a short time – unlike in classic fluorescence microscopy where the light probe and the target molecule bind together permanently. Short, fluorophore-labeled DNA strands are used as protein-binding probes. These only bind briefly and then diffuse again, as is typical of PAINT. Using protein-specific DNA sequences, proteins can be visualized one after the other in the same cell, a process known as multiplexing. “This allows us to visualize a larger number of proteins one after the other than with conventional fluorescence microscopy.” In this procedure, each type of protein is painted in its own “color”.

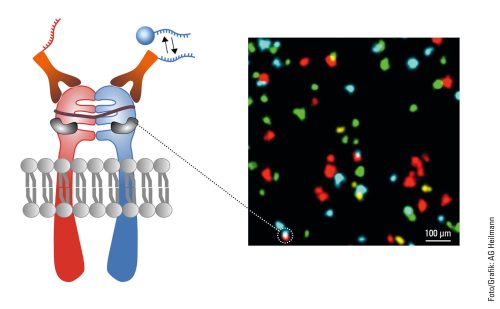

This can be seen in a multiplexing image: many small green, yellow, red and blue dots against a black background. Like a night sky full of colorful twinkling stars. The “stars” in this case are proteins in the cell membrane, the fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR). There are four different types. The red dots are FGFR1, the yellow FGFR2, the green FGFR3 and the blue FGFR4. Some proteins are close to each other, as can be clearly seen. There is a red-blue protein pair, as well as a red-green and a blue-yellow one. Such interactions can also be visualized with multiplexing. And if more complex structures with more than four different types of protein need visualizing? “We can extend this technique and visualize many more proteins.”

It’s the flashes of light that count

In the next step, Heilemann and his team are endeavoring to filter out hidden information from the images with the help of physical “tricks” because they have noticed something: A fluorescent probe on a target molecule does not emit just one flash of light but instead several signals. “The frequency tells us the number of molecules at this position. This means that we can characterize densely packed proteins there that we cannot resolve spatially even with high-resolution microscopy.” The study of molecular processes on the nanoscale in both healthy and diseased cells is another important step. After all, what happens in a healthy cell is different to the process in a diseased cell. The researchers want to identify these differences. There are also plans to analyze the effect of active substances on these processes. Heilemann hopes that super-resolution microscopy will help to ensure major advances in basic research. Understanding the exact composition of protein complexes and their dynamics will form an important basis in the future for the development of targeted drugs against diseases.

About Mike Heilemann

Mike Heilemann studied chemistry in Constance, Heidelberg and Montpellier from 1996 to 2001 and completed his doctoral degree in physics in Heidelberg and Bielefeld from 2002 to 2005. Research stays in Oxford, Bielefeld and Würzburg followed. He has been a professor at the Institute of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry since 2012. He is a member of the German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry, the European Light Microscopy Initiative, the Biophysical Society, the European Photochemistry Association, and SPIE, the international society for optics and photonics. Heilemann is a Principal Investigator of the SCALE cluster initiative (https://scale-frankfurt.org) at Goethe University Frankfurt. The research alliance develops novel technologies to map the internal structures of cells and predict their behavior.

Der Autor

Andreas Lorenz-Meyer, born in 1974, lives in the Palatinate and has been working as a freelance journalist for 13 years. His areas of specialization are sustainability, the climate crisis, renewable energies and digitalization. He publishes in daily newspapers, specialist journals, university and youth magazines.