An interdisciplinary project seminar held in late 2025 at Goethe University Frankfurt fostered students’ grasp on art history and history. The focus was on a collection of medieval and some early modern manuscript fragments, due to be displayed at Eschborn Museum and City Archives. The students designed the exhibition, the catalog as well as online resources for further exploration.

Emma Vier, Kaya Walter and Isabell Schumann all agree that the interdisciplinary project seminar “Medieval Texts and Images from the Hanny Franke Collection” constituted a truly special milestone of their academic journey. The opportunity to not only study objects theoretically but also handle and examine them directly is a rare experience during university courses. “I really enjoyed this hands-on work,” says Kaya Walter. When she flips through the catalog filled with student contributions, she feels genuinely proud of what they have accomplished.

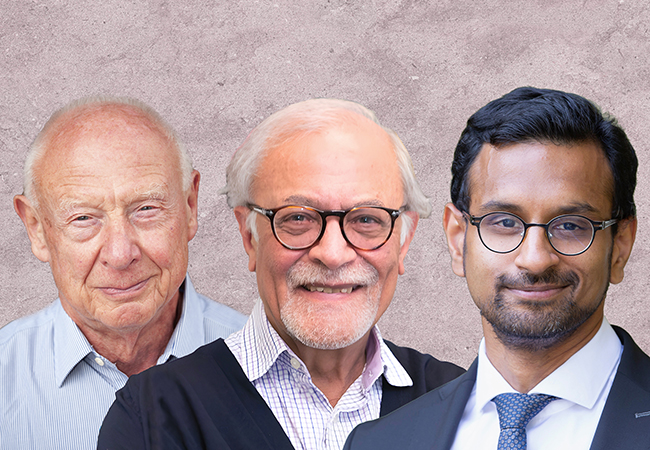

From a student perspective, it definitely was a stroke of luck that Dr. Peter Lingens, director of Eschborn Museum, approached Frankfurt University Library with a rather unique request, seeking professional and practical support to make the Hanny Franke Collection accessible to the public. The library referred him to the academic community. Art historian Prof. Kristin Böse immediately embraced the idea of involving students and, together with Prof. Sita Steckel, her colleague from the department of history, developed a concept for the collaborative seminar.

Hanny Franke and His “Art Collection”

Back in 1991, the city of Eschborn received the artistic estate and art collection of Hanny Franke (1890–1973), a landscape painter well-known in the Frankfurt area, whereby “art collection” should be understood in a very comprehensive sense: the estate includes antiques and archaeological items, sculptures, drawings, and paintings from various eras, objects connected to Hildegard von Bingen, as well as medieval illuminated manuscripts and manuscript fragments. The collection was initially placed in a repository, from where it is now gradually being brought into the public eye.

There was, however, some urgency regarding the book art: the illuminations – this is the term used to describe medieval book painting – and fragments were mounted in acidic mats and required restoration to prevent further damage. A total of 41 freshly restored pieces is now ready to be displayed. Kristin Böse and Sita Steckel not only brought the necessary expertise but also the willingness to take on this task.

Equally committed were 25 students of art history and history, who enthusiastically engaged with the project, and each worked on a specific object. Excursions to Eschborn to view the originals as well as to Mainz provided valuable academic insights, as did a visit to a manuscript exhibition at Frankfurt’s Museum Angewandte Kunst. Dr. Christoph Winterer from the Scientific City Library in Mainz offered the students significant guidance in analyzing and cataloging the individual exhibits. Janne de Loop from Mainz and Oleksandr Ohkrimenko from Birmingham oversaw the cataloging and description of the remaining 16 objects.

With one exception – a Book of Hours from France dating to the late 14th century – the collection consists exclusively of fragments, mostly individual pages from manuscripts or early printed works. Hanny Franke apparently selected the parchment pages based on artistic criteria and even displayed some of them in his home. Due to the intricate book painting, he often framed the pages with the reverse side, i.e. the one featuring the precious illumination, facing outward. Most of the texts were prayers or sacred music, reflecting Franke’s own religious grounding. While working on the project, the students felt that, over time, they were also getting to know the personality of the collector.

The fragments include individual pages as well as decorative initials cut out from larger sheets. Isabell Schumann worked on an especially small object measuring just 6.5 x 6.4 centimeters. The word “VESPRES” is written in capital letters beneath an image depicting a mother with a small child and three other figures. This piece, one of the later fragments in the collection, dates to the 17th century. Schumann was able to link the text on the reverse side to a Bible passage pointing to a Book of Hours. What remains unclear, however, is whether it was a printed work or a manuscript and what types of pigments were used for the colors. These are just some of the questions that required an answer, with the information meticulously compiled and incorporated into the catalog text. A virtual edition of the Eschborn exhibition, which also explains connections between medieval book culture and the history of the collection, is available online: https://tinte-und-gold.de.

The Secret of a Matchbox

The description of a curious artifact can also be found here: a matchbox covered with parchment fragments, apparently used by the collector himself. Pieces from various medieval books were cut up and glued onto the cardboard to create this object. It is unclear whether Hanny Franke made this item himself. What is certain is that today, old textual traditions are handled much differently, with the removal of individual pages considered objectionable not only by experts.

The exhibition could mark a starting point for digitally reuniting the manuscripts: alongside the work on the catalog, the fragments are also being entered into the “Museum Digital” archive as well as the scholarly database “Fragmentarium,” which is accessed and worked on by experts worldwide. “This means our students’ work is made directly visible to the flourishing research field of digital fragment studies,” says Prof. Sita Steckel. The project also benefits teaching within the participating faculties of history and art history: “The increased supervision effort was absolutely worthwhile. This is actually the ideal form of teaching,” says Prof. Kristin Böse.