On the ambivalence of interfaith relationships on social media

Today, believers from the widest variety of traditions come together on social media like never before – spontaneously, visibly and publicly. But what does that mean for interfaith relationships? A complex field of tension is unfolding between mutual understanding and sharp divisions, between digital alliances and polemics amplified by algorithms.

Screenshot: Homepage www.shalomundsalam.de des Vereins Kubus e.V.

Religion is deeply ambivalent. On the one hand, the ambiguity of religious phenomena and their social impact makes religions a resource for solidarity, meaning and peace, but on the other hand also for exclusion, radicalization and claims to power. This ambivalence also clearly comes to light in digital spaces, most notably on social media. Social media does not simply mirror the offline world; instead, it creates complex environments with unique dynamics. These are embedded within, interact with, and respond to broader social and cultural contexts. That is why digital religious practice is always also shaped by political dynamics, social discourses and media agendas. At the same time, digital interactions reverberate, changing perceptions, scope for action and forms of religious expression.

In this way, phenomena such as filter bubbles, echo chambers and opinions that are reinforced and influenced through algorithms are unquestionably also shaping interfaith relationships. Digital communication can strengthen convictions, accentuate differences, obstruct critical debate and intensify conflicts. Yet another effect can also be seen: Religious diversity is becoming more visible, both within individual communities and with regard to interfaith exchange and understanding. Social media enables the simultaneous coexistence of the widest variety of religious voices, approaches and perspectives that in the past were scarcely perceptible on that scale in the public domain. It is from this field of tension that new forms of negotiation and interreligious encounter emerge.

Diversity and digital dynamics

Screenshot: Instagrampage @thequeerarabs

Pluralization and superdiversity (Vertovec, 2019, 2023), common features of today’s societies, are also radically transforming the religious realm. New religious groups, forms of community and civil society initiatives are emerging, while patterns of interpretation, normative orders and religious self-positioning are shifting. Religious knowledge is becoming itinerant, changing and connecting with other forms of knowledge, cultural expectations and political discourses. As a result, authority, identity and religious argumentation are subjected to constant processes of negotiation, both within religions and in interreligious encounters.

Digital spaces not only reflect these transformation processes but also actively contribute to them. This is because real-time interaction, rapid dissemination of information and constant exchange of data mean that users are no longer passive recipients or consumers, but instead become active shapers of digital publics and thus also of religious and interreligious spaces. Here, interreligious communication does not take place on a single platform but rather in a network of spaces linked by hypermedia. These dynamic, hypermediated spaces (Evolvi, 2022) connect online and offline worlds as well as different platform logics. Users actively shape and redesign them time and again. This creates new publics, and marginalized voices become audible or claim space. At the same time, religious authority is shaped less and less by institutional legitimacy and far more by reach, resonance and performative presence, for example through influencers or online preachers. These stakeholders present religious content in a media-savvy way and mold new authoritative structures. At the same time, denominational and non-religious boundaries are becoming more permeable: Popular culture, activism and lifestyle are fusing with religious communication. The outcome is fluid communities, interfaith neighborhoods and temporary publics that redefine the religious landscape.

(Inter)religious communication beyond conventional boundaries

Digital media are changing not only who speaks but also where and how they speak as well as what they say. By dismantling traditional spatial categories (local, global, transnational), religious communication goes beyond geographical, cultural and social boundaries. This can clearly be seen in the context of migration, in particular: Digital platforms enable simultaneous participation in discourses in both country of origin and host country. Hybrid publics are emerging in which transcultural experiences, collective memories and new patterns of interpretation are intertwined. In this way, digital media make it possible for people to engage more easily, quickly and extensively in global debates – in the religious domain too.

Religion as a discursive interface

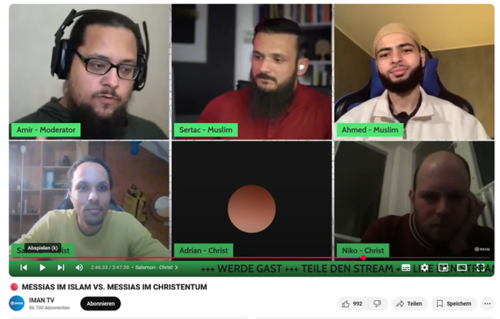

Screenshot: Youtube @imantv Livekonferenz am 15. Januar 2025

This is also transforming the thematic focus of religious and interreligious discourse. Today, it is often directly associated with social issues such as culture of remembrance, global crises and political conflicts. Here, religion does not manifest itself as a closed system but rather as a discursive interface, a domain that reacts to social problems by constantly reconfiguring itself. Local frames of reference remain important – language, cultural contexts and social backgrounds continue to carry weight in digital spaces too. But the established patterns of coexistence and the lines of demarcation and competition are shifting. In digital interreligious contexts, tensions and rifts are emerging that extend far beyond religious discourse. Polemics, segregation and assertion of identity come particularly to the fore on social media – partly with openly hostile, anti-Semitic, racist or Islamophobic content. The spread of conflict-laden narratives is fueled by emotionalization, polarization and viral logic amplified by algorithms, turning the digital space into a stage for symbolic battles, a screen for projecting social anxieties and an arena for collective negotiation. At the same time, however, social media is also a place where strategic alliances often appear – new forms of solidarity and cooperation between members of different religions. These pertain to common areas of social action, such as anti-discrimination work, human rights issues, positioning in political debates, or campaigns against hate speech and religious marginalization. Such alliances often form at the interface between digital networking and local presence: Encounters take place online, but their effects extend far beyond the digital sphere – and vice versa.

Mediatization and aesthetic practices

The establishment of interfaith relationships in the digital space goes hand in hand with their mediatization: They become visible, observable and communicative – for example through videos, images, memes or multimodal text-image formats. Interaction with religion hence takes place not only at the level of content but also through visual and audiovisual scenarios and formats.

In this context, platform logic plays an important role. Social media is not neutral. Instead, it structures interactions through what are known as “affordances” – potential actions that are enabled and at the same time limited by design, functions and social expectations. It influences proximity and distance and how relationships remain visible or hidden. Here, it is not only interactions such as following, liking or commenting that shape the relationship between religious stakeholders but also the platform architecture itself: Algorithmic logic, economic interests (e.g. advertising), state regulation and moderation mechanisms substantially influence the space of digital religious communication. Media framing acts as an invisible player in interreligious encounters. At the same time, affordances are not rigid rules, but variable practices modeled by society (cf. Schröder & Richter, 2022). Through their behavior, users co-shape the platform structures so that these become places of discursive negotiation and spaces for interreligious dynamics to resonate.

The concrete forms of expression of interreligious dynamics are many and varied. One example is the dissemination of religious knowledge by influencers who represent their own religion and sometimes invite members of other traditions to discuss questions of faith. In many cases, the chosen setting is an interreligious dialog – sometimes informative, sometimes performative, sometimes didactic. However, not all activities are characterized by a claim to equality. Social media affordances allow asymmetrical structures to present themselves as dialog formats. If, for example, one group controls what topics are discussed and constantly takes the stage while other groups are involved only occasionally, this can lead to a power imbalance, even if this is concealed rhetorically or visually by the “dialog setting”. Furthermore, platform logic favors stakeholders with reach or media clout, which encourages subtle one-sidedness in interreligious encounters. These dynamics can especially be seen in formats such as street interviews or debates, where individuals appear as representatives of certain religions and discuss in public, accompanied by an audience that is physically on site or digitally present in the comments section. The combination of random aesthetics and orchestrated confrontation – amplified by cropping, camera angles and audience reactions – creates a dramatized form of interreligious encounter. This achieves a wide reach, but the dialog often lacks depth because the focus is not on awareness or understanding, but on polemical escalation aimed at presenting a “victor”.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Religion can be a foundation for peace and a sense of community, but it can also divide and radicalize. These tensions are particularly evident on social media.

- Social media does not simply reflect the real world. It actively contributes

to shaping religious forms of expression, shifts authorities and creates new possibilities (and challenges) for religious encounters. - Digital publics are dynamic, polyphonic and often cross geographical, cultural and religious boundaries. At the same time, social media enables new forms of visibility for religious minorities and voices so far marginalized.

- Algorithms, mechanisms for increasing reach, and visual settings determine which religious voices are audible on social media. This can foster genuine dialog – or else distort it through power imbalances, polemics and performance.

- Whether through influencers, queer religious communities or activist alliances: New forms of religious authority, new religious publics and new spaces for encounter are evolving online.

New visibility for marginalized groups

On the other hand, digital profiles and posts by groups or organizations that form interreligious alliances – such as queer believers – create new visibility and media counterspaces. These are often directed at target groups that are religiously diverse to begin with. Here, interreligiousness is not additive but constitutive: A multi-religious public becomes the norm. These digital practices consciously position themselves against hegemonic ways of speaking and change not only the image of religion but also interreligious fields of action.

Despite all their differences, it can be said for all the formats mentioned above that they contribute to a refiguration of interfaith relationships under the conditions of digital media. The diversity of stakeholders, their respective publics and potential interpretations as well as the possibility for rapid networking across various platforms create a dynamic space in which religious differences can lead to separation and segregation, but in which this does not, however, necessarily have to happen: Religious differences can at the same time become a starting point for new forms of dialog and understanding.

The author

Armina Omerika, born in 1976, is Professor of Intellectual History of Islam at Goethe University Frankfurt. Her research interests are modern Islamic thought as part of global intellectual history, Islam in Southeast Europe, historical images of Islamic theology, as well as Islam and interfaith relationships in digital spaces. She heads the research project “Islam and Digitality: Mediality, Materiality, Hermeneutics” (BMBF/AIWG, 2024-2026) and has been deputy spokesperson of the research alliance “Dynamics of Religion. Ambivalent Neighborhoods between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in Historical and Contemporary Constellations” since 2024. In addition, she is involved in political education and inter-faith dialog and heads the podcast project “theofunk”.

omerika@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding

Literature

Evolvi, Giulia: Religion and the Internet: Digital Religion, (Hyper)Mediated Spaces,

and Materiality, Z Religion Ges Polit 6, 2022, p. 9–25, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41682-021-00087-9

Schröder, Christoph and Christoph Richter: Relationale Affordanzen: Oder die Möglichkeit einer ‚fantastischen Authentizität‘ auf Instagram, in Böhnke et al. (eds.): Spuren digitaler Artikulationen: Interdisziplinäre Annäherungen an Soziale Medien als kultureller Bildungsraum, Bielefeld, 2022, p. 139-170, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839459744-005

Vertovec, Steven:

Superdiversity – Migration

und Social Complexity. London, 2023.

Vertovec, Steven: Talking around super-diversity,

Ethnic and Racial Studies 42, no. 1 (2019), p. 125-139