Raphael Straus firmly believed in the bonds between Jews and Christians – even during the Nazi terror

Photo: Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

In the early 1940s, a Jewish scholar who had fled from the Nazis to Palestine wrote “Eine friedvolle Betrachtung über Judentum und Christentum” (“A Peaceful Contemplation on Judaism and Christianity”). Who was Raphael Straus? And where did he find the strength to promote understanding in the midst of the Holocaust?

Little is known about the life and death of Raphael Straus. Together with his wife and four children, the German scholar, who was of Jewish faith and an expert on medieval Jewish history, fled from Nazi persecution to what was then the British-administered territory called Mandatory Palestine, now Israel, in 1933. But Straus, who had advocated the establishment of a Jewish nation-state in Palestine since his youth, was never able to really gain a foothold in Jerusalem. He tried in vain to find a position at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which had opened in 1925. Straus kept his head above water through scholarships and work in adult education. In 1945, he emigrated to New York, where the German-Jewish scholar, largely forgotten by his contemporaries, died of a heart attack at the age of only 60.

Dead, forgotten and rediscovered

“It might well be that his fate – emigration, exile and a precarious existence – contributed to his early death,” says Christian Wiese, holder of the Martin Buber Chair for Jewish Religious Philosophy, who as a Jewish studies scholar is studying the life and work of Raphael Straus and finds one of his works particularly impressive: Despite the persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany, despite the reticence of most Christian theologians and believers, in his unpublished work “Apokatastasis. Eine friedvolle Betrachtung über Judentum und Christentum” (“Apokatastasis. A Peaceful Contemplation of Judaism and Christianity”), written in around 1940 and still unpublished, Straus upheld his interpretation of the two religions as neighbors, which he considered to be intertwined by similarities in religious doctrine as well as a history of social relations and economic interdependence stretching back thousands of years. Straus probably borrowed the term “neighborhood” from James Parkes (1896-1981), an Englishman, Anglican theologian and activist for Christian-Jewish understanding.

This makes Raphael Straus’ work a suitable case study in the context of the interdisciplinary research project “Dynamics of Religion: Ambivalent Neighborhoods between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in Historical and Contemporary Constellations”, whose academic spokesperson is Christian Wiese. In this project, Wiese has joined forces with colleagues from disciplines such as Jewish studies, Islamic studies, religious studies and history, archaeology and ethnology, as well as social and educational sciences to build a prominent international research network, in which scholars from Goethe University Frankfurt, Marburg University, JLU (Giessen University) and other partner institutions are collaborating. The goal of this research into the neighborhoods between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in history and the present day, and in their various forms, from successful coexistence to violence and genocide, is to lay the groundwork for educational strategies aimed at combating religiously motivated hate.

On November 10, 1938, a woman walks past a Jewish printworks in Berlin, whose windows have been smashed by the Nazi rabble. Raphael Straus experienced from a distance the steadily escalating terror.

Photo: Picture Alliance/AP Images

IN A NUTSHELL

- Despite Nazi persecution, the Jewish scholar Raphael Straus firmly believed in an understanding between Judaism and Christianity. He stressed that the two religions were historical neighbors with an intellectual connection.

- In 1933, Straus fled to Palestine with this family but never managed to gain

a foothold there. Scholarships and

jobs in adult education enabled him to make ends meet. He later emigrated

to the USA. - Straus was deeply shocked by the reaction of many Christian theologians, who distanced themselves from their Jewish “neighbors” during the Nazi era and supported anti-Semitic assertions.

- In his paper on the Jews in Regensburg in the Middle Ages, Straus criticized the one-sided portrayal of Jewish history as a sequence of persecution and pogroms and presented the economic and cultural interrelationships of Jews and Christians.

- Almost forgotten during his lifetime, Straus’ work is today being rediscovered. For Christian Wiese, Jewish studies scholar at Goethe University Frankfurt, Straus’ “peaceful contemplation” constitutes an important contribution to Christian-Jewish under-

standing and moral reflection on the responsibility of theology in times

of hate.

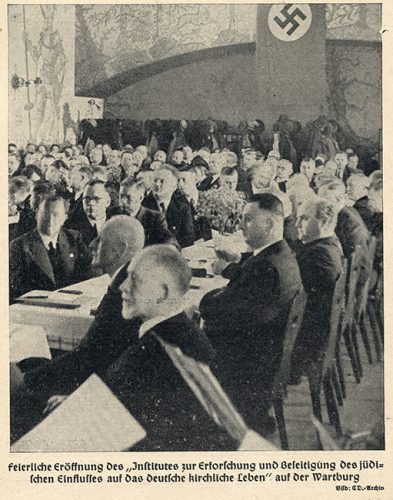

Betrayal and self-betrayal

Raphael Straus had observed the effects of hatred from afar while in exile in Palestine: The steady, unprecedented escalation of anti-Semitic persecution and violence in Germany from 1933 onwards, with the Nuremberg Race Laws introduced in 1935 and the pogroms that took place between November 7 and 13, 1938, when shops and synagogues throughout the German Reich were set on fire and thousands of Jews were deported to concentration camps, tortured and murdered, culminating in the Nazi’s systematic extermination policy during World War II. Straus was deeply shocked by the reaction of many Christian theologians to the atrocities: Instead of showing solidarity with their Jewish “neighbors in spirit,” theologians, even those in the Confessing Church, which was, in fact, critical of Nazism in some respect, advocated an “emancipation” of Christianity from the “pressure of the Jewish spirit.” Nazi theologians associated with the “Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life,” founded in Eisenach in 1939, even claimed that Jesus had been an “Aryan” who had sought conflict with Judaism for racial reasons and had, therefore, been crucified. This line of argument meant that even a Christian justification for the anti-Semitic volition to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population was no longer ruled out.

A moral force that still echoes

“Against this backdrop, Straus’ imploring emphasis of the historical ‘community of destiny’ of Judaism and Christianity can be read as a desperate attempt to create a counter-history aimed at refuting attempts to demarcate Christianity from everything Jewish,” says Christian Wiese, Protestant theologian and Jewish studies scholar. It was by chance that Wiese came across a copy of Raphael Straus’ typescript while conducting research at the Salomon Ludwig Steinheim Institute of German-Jewish History at the University of Duisburg-Essen in the late 1990s. The original is kept in Jerusalem, along with other materials. Wiese later discovered a card index box with notes and citations for the footnotes at the Leo Baeck Institute in New York. For an edition of the work, it would first be necessary to assign the bibliographical references to the respective passages in the text. According to Wiese, processing and researching Straus’ estate would be a complex task. “Furthermore, it was questionable back then whether a publisher could be found for a scholar like Straus, who had been largely forgotten even among academics,” recalls Wiese, who at the time was working on his postdoctoral dissertation (Habilitation) on the life and thought of Hans Jonas, the great German-Jewish-American philosopher.

Meanwhile, Straus’ notes are accessible at least in a digital format in the New York archives, and Christian Wiese now intends to explore and publish the historian’s work, which has fascinated him since his time at the University of Duisburg-Essen, as part of the “Neighborhoods” research project. “For me, it’s important to place Straus’ ‘peaceful contemplation on Christianity and Judaism’ in its historical context,” says Wiese, explaining his scientific interest and what motivates his research: “As a lonely conversation between an exiled Jewish scholar and a Christian theology that profoundly failed in its responsibility towards Judaism, but also as an expression of desperate hope for Christian solidarity in the darkest times, the moral force of Raphael Straus’ work deserves to be acknowledged.”

Source: Landeskirchenarchiv Eisenach

An astonishingly modern intellect

Wiese has already established that Raphael Straus’ perspective on the relationship between Christianity and Judaism was remarkably modern compared to contemporary thinkers still better known today such as the liberal Protestant theologian Adolf von Harnack or the equally liberal rabbi Leo Baeck. Straus interpreted the intensifying conflicts between Judaism and Christianity at the beginning of the 19th century as an attempt by representatives of both sides to defend their respective religious identities – precisely because the differences in religious practice and lifestyle had blurred as the two religions adjusted to modernity. Straus called on both Christian and Jewish theologians to rise above the bias of their own religious ties and take an unprejudiced look at each other’s religion. Then, he believed, they would see how close Jewish and Christian doctrines were. For him, Christianity remained connected to Judaism because “its God had once been a Jewish fisherman, its ‘Mother of God’ a Jewish carpenter’s wife, its prophets Jewish men from here and there, its Holy Scriptures and teachings of Jewish origin, its happiness and future, and that of all humankind, bound to the happiness and future of the Jews.”

“Straus’ portrayal gains its critical power when he characterizes the anti-Semitic dissociation from the ‘Old Testament’ as an absurd illusion, even as a radical loss of self that threatens to damage Christianity at its roots,” summarizes Christian Wiese. The fact that Straus came from an orthodox, i. e. traditionally Jewish family, makes his readiness to engage in dialogue all the more surprising. Straus set an example of what he demanded of his contemporaries.

Where did this intellectual agility come from? “We don’t know yet why Straus’ academic work does not reflect his originally orthodox background,” says Christian Wiese. He considers Straus’ historical self-image to be a possible reason. In his 1932 work “The Jewish Community of Regensburg at the End of the Middle Ages,” which remains his best-known work to this day, Straus critically examined the history of the Jewish community in Regensburg and presented a new version on the basis of primary sources. In his study commissioned by the Historical Commission of the Association of Bavarian Jewish Communities, Straus examined in detail the economic, social and cultural interrelationships between Jews and Christians since the Middle Ages. “In doing so, Straus already anticipated, in 1932, trends in contemporary historical research and rejected what he called a ‘lachrymose narrative’ that portrayed the history of the Jews in Europe in the Middle Ages as a mere succession of persecutions and pogroms,” explains Christian Wiese.

Betrayed and burned

Straus’ efforts to promote interfaith understanding based on shared history were a thorn in the side of the Nazis. Wilhelm Grau, a doctoral student from Munich who masqueraded as a democrat and a “friend of the Jews” and claimed to be preparing an exhibition on the history of the Jews in Regensburg, tricked Straus into trusting him, obtained his still unpublished “Documents and Records on the History of the Jews in Regensburg at the End of the Middle Ages”, then plagiarized and distorted them in an anti-Semitic fashion. In 1938, the Gestapo burned the galley proofs of Straus’ “Documents and Records,” but a few copies survived. It was not until 1960 that this work was published in Germany, thanks to the connections of Jewish historian Guido Kisch to Straus’ widow Erna.

About

Christian Wiese, born in 1961 in Bonn, is a Protestant theologian and Jewish studies scholar. His main research interests are Modern Jewish religious philosophy, Jewish-Christian relations, antisemitism research, and Jewish thinking after the Holocaust. Wiese earned his doctoral degree at Goethe University Frankfurt in 1997 and his postdoctoral degree (Habilitation) in religious and Jewish studies at the University of Erfurt in 2006. From 2007 to 2010, Wiese was director of the Center for German-Jewish Studies and professor for Jewish history at the University of Sussex. Since October 2010, Wiese has held the Martin Buber Chair for Jewish Religious Philosophy at Goethe University Frankfurt. Since 2021, he has headed the Buber-Rosenzweig Institute for Modern and Contemporary Jewish Intellectual and Cultural History at Goethe University Frankfurt.

C.Wiese@em.uni-frankfurt.de

The author

Jonas Krumbein, born in 1985, studied history and political science in Freiburg and Durham (England) and works part-time as a freelance journalist.

j.m.krumbein@icloud.co

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding