Questions to the comparatist Achim Geisenhanslüke on the dialog between the philosophers Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jacques Derrida

Photo: Picture Alliance/dpa/Matthias Ernert

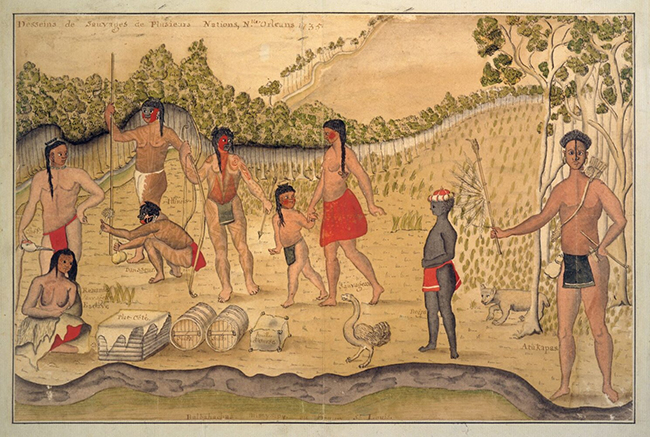

In April 1981, a momentous encounter between two great thinkers took place in Paris: Hans-Georg Gadamer, at that time the figurehead, as it were, of hermeneutics in Heidelberg, met Jacques Derrida, the Parisian intellectual and best-known representative of deconstruction, at an event organized by the Goethe Institute. Two completely different concepts of linguistic understanding collided: The one gentleman aspired to achieve understanding through conversation or reading, even if this was associated with considerable effort, while the other argued the case that understanding might be impossible. Yet despite (or perhaps because of) these differences, a close intellectual bond developed between the two men after this meeting, which lasted for many years. Gadamer passed away in 2002 at the age of 102, and Derrida gave the ceremonial address at the academic memorial service on the first anniversary of his death.

English edition

New York 2016

Dirk Frank: Professor Geisenhanslüke, a meeting like the one between two such opposing thinkers is presumably rather rare in the history of philosophy, isn’t it?

Achim Geisenhanslüke: Yes, it is indeed rather rare, but we are, of course, familiar with such more or less heralded debates from the history of religion, for example the Colloquy of Regensburg in 1541, which was about a possible agreement between Catholicism and Protestantism. And that no agreement is reached in these debates is mostly commonplace. That was the case with Eck and Melanchthon, as well as with Gadamer and Derrida. But the dispute is slightly reminiscent of a religious quarrel between two parties inclined to assert their own claims, which are always also a claim to power, in the course of the discussion. This is something that happens quite often. Take, for example, the discussion here in Frankfurt between Axel Honneth and Jacques Rancière in June 2009 at the Institute for Social Research: acknowledgement and consensus versus disagreement and dissent, with no tangible result there either.

Does any discourse at all take place in academic practice between such different schools of thought, or do people tend – casually speaking – to stay in their own “bubbles”? Are there perhaps limits to understanding?

Yes, there are, as both Gadamer and Derrida point out in their debate. The actual point of contention is hermeneutics’ universal claim, which is certainly compatible with the idea that there can also be limits, a claim that Derrida is unwilling to share. It is somewhat reminiscent of the old dispute between Plato, to whom Gadamer explicitly refers, and the Sophists, that is, the dispute between philosophy, with its attempts to develop a concept of reason, and rhetoric, which insists that all ideas are dependent on language. This is what makes Gadamer’s argument – “Being that can be understood is language” – a red rag to deconstruction: Language is not automatically understanding; there is an agonistic moment, a kind of contest that hermeneutics denies. That is the crux of the dispute.

Photo: Picture Alliance/AKG-Images

In philosophical hermeneutics, the category of understanding is of central importance, according to which discussion can provide a foundation for understanding – albeit an unstable one. Derrida’s theory of deconstruction, by contrast, is rather a kind of subversion of all attempts at establishing such a foundation. Those are not really ideal conditions for academic discourse, are they?

One of the distinctive features of academic discourse is that different opinions can subsist alongside each other. There is a freedom here that distinguishes the university and its associated hermeneutics from theology or law. A court is obliged to reach a verdict, but that is not the case here. In that sense, the university is precisely the institution where such a dispute finds its forum. It only becomes problematic when the differences entrench themselves as dogma.

Both thinkers refer, if in different ways, to Martin Heidegger and his critique of modernity. For both, language is the key to a world beyond a strictly science-based way of thinking. Gadamer and Derrida both dealt with literature and especially with poetry, for example with Hölderlin and Celan. In what ways do they differ in this respect, and where do you, as a literary scholar, see (more) instructive approaches?

That both refer to Heidegger is one of their main commonalities. However, in my view this is not particularly fortunate because Heidegger caused immense damage both as a philosopher and as a political player in the university landscape, which he, of course, also was. Both are part of the same tradition that remains highly problematic, and their interpretations of literature continue to depend on Heidegger to a certain extent. Derrida’s adherence to Nietzsche suggests, however, that he is more sensitive to the resistance against Heidegger. In any case, he uses Nietzsche’s philosophy of language, which is characterized by a close affinity with literature, too, to correct Heidegger’s ontological thinking. That is why Derrida’s Heidegger is not the same as Gadamer’s. But that was nevertheless not a particularly good starting point for interpreting Hölderlin and Celan. As a literary scholar, I would like to highlight a third position, that of Peter Szondi, who also studied Hölderlin and Celan in depth, not from the perspective of philosophical hermeneutics or deconstruction, but rather from that of literary hermeneutics. This seems to me to be a very promising approach.

The dialog between Gadamer and Derrida was not just one between philosophers from different schools of thought but at the same time also one between a German and a Frenchman. To what extent did the cultural and historical differences between the two nations and cultures, their self-image and perception of others, sculpt their discussion and dispute?

Photo: Picture Alliance/Design Pics/Ken Welsh

National stereotypes often play a role. Nation is one thing, religion, as already intimated, is another. In any case, a German and a French position collided, but also a Protestant and a Jewish one. We should not forget this, especially given Heidegger’s dual background. Gadamer was strongly influenced by a belief in the true word, as we are also familiar with from theology. Derrida, by contrast, is in favor of a playful handling of language, which in Germany is quickly criticized as being “irresponsible”. Schleiermacher referred to the Kabbalistic interpretation in such terms. Belief in the power of footnotes is very pronounced in the German academic system, whereas the French approach to them is more relaxed. At the same time, there is this tremendous fascination in France with Germany, with thinkers such as Heidegger and Nietzsche, and we can learn a lot about ourselves from this fascination.

Martin Gessmann, who also edited Gadamer and Derrida’s joint book “Der ununterbrochene Dialog” (“The Uninterrupted Dialog”), described the two of them as opposites: the “pacifier” (Gadamer) and the “seducer” (Derrida). While the former sees everything as having already existed and wants to relate the unknown to the known and its precursors, the latter finds everything fundamentally astonishing that cascades over us unpredictably and momentously. To what extent does this fit in with the German-French culture-nature dichotomy, or does it even contradict it?

I don’t think “pacifier” and “seducer” are accurate descriptions, and if they are, then both of them are both. Gadamer was incredibly charismatic, as many have testified, and Derrida was similar. Both refer to the history of metaphysics as a matter of course, with different emphasis and weighting, but in so doing they both ultimately signal that they are philosophers in a rather traditional sense. There are fundamental commonalities that made their dispute possible in the first place, and these commonalities can also be critically questioned: Does it exist at all, the history of metaphysics in this form?

You are a comparatist and deal with literature and literary theory. In what way is this debate between hermeneutics and deconstruction still relevant for literary studies today? Have other, perhaps more important theoretical positions developed since then (which you perhaps also incorporate in your own work)?

The debate meanwhile seems slightly anachronistic. The dispute between hermeneutics and deconstruction is more or less over, but not in the sense that one side has won and the other one lost, but rather that at some point the conclusion was drawn that it no longer really interests us. Today, the questions of understanding raised by hermeneutics tend rather to be tackled by the cognitive sciences, meaning they have migrated to the natural sciences, while deconstruction has lost much of its institutional appeal. In fact, it was only an academic success in the United States anyway, not in France or Germany. What remains for comparative literature, or rather general and comparative literary studies, is the spirit of criticism personified by someone like Derrida, as well as the fascination with French thinking as a different tradition from which we can learn without forgetting our own. This also includes respect for Jewish tradition, as seen in the work of Shoshana Felman and others, in which literary scholars such as Szondi stand, as do philosophers such as Derrida, but of course also experts in psychoanalysis, alongside Freud. What unites these so different thinkers is a kabbalistic-like attention to the literal side of interpretation, to the materiality of language, which is completely opposed to the primacy of the intellect. For me, it remains the responsibility of general and comparative literary studies to remember and pursue that tradition.

About

Achim Geisenhanslüke, studied general and comparative literary studies and philosophy in Berlin and Paris (which already highlights his affinity with the other side of the Rhine). He has been Professor for General and Comparative Literary Studies in Frankfurt since 2014. His main interests are French literary theory (e.g. Foucault, Derrida) and psychoanalysis (here, too, with a focus on France (Lacan and Laplanche, alongside Freud). During the semester breaks he lives in France (Lacanau-Océan, Nice).

The interviewer

Dr. Dirk Frank

is Deputy Press Spokesperson of Goethe University Frankfurt

frank@pvw.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding