Interview with Susan Goldin-Meadow, pioneer of psychological and linguistic gesture studies

We all communicate not only with words but also with gestures and facial expressions. For a long time, these visible actions scarcely played a role in research on human communication. Professor Susan Goldin-Meadow has immersed herself for many years in this field, which opens up new perspectives in psychology and linguistics.

Anke Sauter: “Thinking with Your Hands: The Surprising Science Behind How Gestures Shape our Thoughts” is the title of your book published in 2023. Do your own gestures sometimes surprise you?

Susan Goldin Meadow: When I lecture, I try to be aware of how I am using my hands and whether I am using them consistently. But, at times, gesturing does just happen – I notice that my hands go up in the air, particularly when I get enthusiastic about something I’m talking about.

Is this reflection on your own gestures the reason for your research on this topic?

I have always used my hands a lot when I talk, but that is not the reason why I became interested in gesture. I discovered it in quite another way: I wanted to know where language comes from, and to find that out, I studied deaf children, whose hearing losses were so profound that they could not learn the spoken language around them, and whose hearing parents had not exposed them to sign language. Nevertheless, they created their own gesture system, called homesign. I wanted to know whether their system was influenced by their hearing parents’ gestures, which meant that I had to study the gestures that hearing speakers produce when they talk. I compared the gestures produced by the deaf children’s hearing parents to the deaf children’s homesigns and found few similarities. I also compared the gestures produced by hearing children to the deaf children’s homesigns to see how far beyond typical gesture homesign is able to go. So my studies of the gestures hearing people produce were, in the first instance, a control for my studies of homesign in deaf children.

What influence did Jean Piaget, the renowned childhood researcher, have on your research? You spent some time with him as a student.

In Geneva, I started to become interested in cognition and thinking, and I discovered how important it is to really watch children. When I got back to the United States and started graduate school at University of Pennsylvania, I started watching children communicate and discovered gesture.

Why was visual communication neglected for such a long time, for example in linguistics?

Linguistics has always focused on speech. So much so that for many years it did not even consider sign language to be a real language. Today, things are different, and gestures are also considered part of communication, associated in particular with prosody* and the dynamics of speech.

*All the sound properties of spoken language (editor’s note)

Of course, in former times it was also more difficult to document gestures.

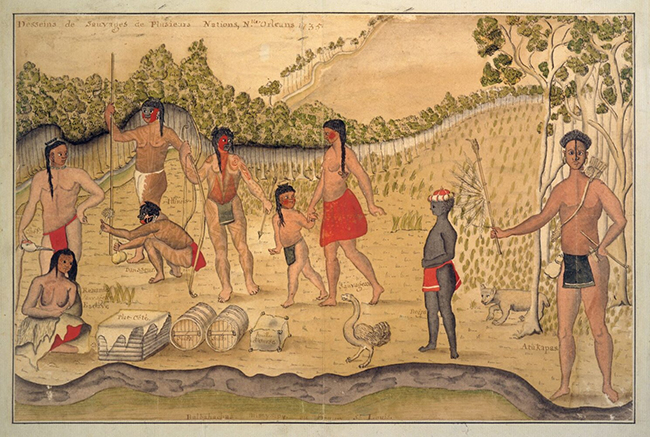

In 1941, David Efron published a book on gesture that had pictures, which he had to draw. He examined whether the gestures of Italians and Jews who had moved to the United States changed as a result of the new cultures they were living in. He argued that gestures are, to a large extent, not innate but influenced by the cultural environment. He was a pioneer of gesture studies.

The amazing thing is that written language works

Nowadays, written language in social media is often accompanied by smileys and emojis. Does this indicate that written language lacks something?

The more amazing thing is that written language works as well as it does since it lacks prosody, facial expressions and gesture. Interestingly, no one has been able to construct a written system for sign language. The attempts to construct a written system for sign must be leaving out aspects of communication that are needed for understanding.

In the “ViCom” Priority Programme, emojis are treated to a certain extent like gestures. Do you agree with that?

Partly. Most emojis express emotions (as the name implies). There are gestures that convey emotion. But there are also gestures that convey content. These substantive gestures are the focus of my work.

People who are blind from birth use gestures even when communicating with other blind people. Why?

The fact that we gesture when we are on the phone when no one is watching us shows that gesturing is a really important part of our behavior. Watch interpreters at work: They sit alone in their booths, yet they are gesturing throughout even though no one is watching them. This suggests that gesturing is part of the process of talking. The fact that blind people do it too suggests that it is not necessary to have ever seen anyone gesture in order to feel the urge to move your hands when you talk.

Gestures help us to organize our thoughts

So we don’t know why we gesture?

Yes, we do, in part. Gesturing lightens our cognitive load, it helps us remember, and it helps us organize our thoughts. But it also helps others by drawing attention to our words and to the world.

What do your studies with deaf children tell us about the origins of human language?

Language, as we know it, is handed down from generation to generation and changes in the course of those generations. What the studies of homesign show is that if you allow a child to grow up without experiencing the language that their community uses, that child can nevertheless invent some aspects of language. So what we find in homesign are the properties of language that are likely to have come

about through biological evolution and not through cultural evolution, that is, through changes over generations of language users.

The origins of human language are not necessarily visual. Nevertheless, the visual language of deaf children can reveal which elements of language are likely to be universal – grammatical categories in sentences, for example.

Exactly. The first language was not necessarily gestural, but humans probably communicated from the very beginning using both sounds and hands. Homesign reveals how humans structure the world when they communicate about it, structure that does not come with the language that has been handed down

to us.

Doesn’t that correspond a little with Noam Chomsky’s theory of generative grammar?

Yes. I think that Chomsky was pleased to hear about homesign and not surprised. But Chomsky attributes far more complex properties to universal grammar than we find in homesign. The properties that we find in homesign are the linguistic properties that most linguists agree on. Things such as sentences, words, word order, but Chomsky’s theory goes far beyond what we find in homesign.

How old were the children you studied? The older they are, the more they are exposed to external influences.

That is true, particularly in the US. But in Nicaragua, there are adult homesigners who live there in a world of hearing people. But the hearing people don’t really know the homesign systems that the deaf adults use. Work by Marie Coppola has addressed this question.

And how far do adult homesigners get?

That is one of the main questions: How far can you get with homesign and at what point is cultural transmission needed to advance the system? Where does homesign stop and sign language start?

Gestures generate new ideas

You have also discovered that a discrepancy between gestures and words spoken at the same time offers great potential for learning. Can you please explain that?

Yes. The mismatch between the information conveyed in gesture and speech is useful for learning in a number of ways. First, the information conveyed in gesture in a mismatch is information that the learner has implicitly but is unable to express explicitly. Second, the information a child expresses in gesture that is not expressed in speech is a signal that the child is ready for instruction on this concept. Teachers may respond to this signal of readiness-to-learn by providing just the right instruction that will benefit the child. We respond to other people’s gestures without even knowing that we’re doing it. If I express an idea that I do not even know I have and someone else responds to that idea, it can be an important source of feedback for me. Encouraging children to gesture can prompt them to express new ideas in gesture and make them more open to instruction. Expressing ideas with our hands makes those ideas more accessible and learnable.

Does this mean that gestures are closer to our mind than spoken language is?

I think that gestures are more concrete, and can make certain ideas more visible, than spoken language. You can use your hands to demonstrate twisting a lid, but the twisting gesture will not result in lid-opening unless someone interprets the movement as an instruction to act. Gesture sits somewhere between actually doing an action and representing the action.

Are gestures more true or even more honest?

That is a good question. One of my students, Amy Franklin, conducted a study in which people were asked to describe an event incorrectly. They described the event as they were instructed to (in other words, they lied), but the truth came out in their gestures.

Could this knowledge about gestures be used in criminology one day?

David McNeill, a well-known gesture researcher, once invited a member of the police department to his laboratory to find that out. I think you would have to be a very astute observer to use gesture in this way.

Gestures as a diagnostic instrument for language development

You have also described the role of gestures in the diagnosis of cognitive development disorders in early childhood.

In small children, gestures can predict the next step in language development. If a child points to a cup and says “Mommy,” the child is essentially saying, “that’s mommy’s cup”. Approximately three months after producing gesture-speech combinations of this sort, the child will begin producing two-word sentences like “mommy cup”. Children with brain damage generally have difficulty producing words. But the children with brain injury who are able to gesture like typically developing children are more likely to learn words at a typical pace than children with brain injury who do not gesture like typically developing children.

This diagnostic method is not used yet?

I think that good clinicians use gesture intuitively, but it is not yet used as systematically as it could be. We need to develop a usable diagnostic tool to evaluate gesture use in children, a goal that I hope we can achieve one day.

The linguist Cornelia Ebert is leading a large-scale project that deals with visual communication. What, in your opinion, are the most important questions?

There are many really interesting questions in the ViCom project. How gesture and speech work together to complement one another. Exploring this question within the framework of linguistics is an excellent approach. But we need to take a closer look: What is the status of the information conveyed in gesture? Is it part of our linguistic representations? If not, where is it encoded? The ViCom team is working on these questions.

There is more that we don’t know than we do know

What is your role in ViCom?

I was a Mercator Fellow for a year and came to Frankfurt twice. I am conducting a study with one of the ViCom researchers, Patrick Trettenbrein from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences. We are looking at sign language and gesture and trying to identify how gesture is used with sign language.

Is there still a lot to discover in the field of visual communication?

There is more that we don’t know than we do know. As a psychologist, I am interested in the role that gestures play in the learning process and how they help us think and learn. There is also a set of questions related to my work on homesign, such as which properties of language came about as the result of biological evolution and which came about through cultural evolution.

You are conducting research in both areas?

Yes. For my research on the role of gesture in learning, we are doing brain imaging. We want to find out what happens in the brain when we express one idea in gesture and a different idea in speech, and what happens when we learn from instruction that includes gesture. Behaviorally, we know that we learn better when we gesture than when we do not gesture, and that we retain and generalize what we’ve learned better when we gesture than when we do not gesture. Our next step is to explain the brain mechanisms that underlie these behavioral effects.

About

Susan J. Goldin-Meadow, born in 1949, is Professor of Psychology at the University of Chicago. She did her bachelor’s degree at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and her Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, earning her doctoral degree in 1975. She also studied in Geneva, Switzerland, under Jean Piaget. She has been a professor at the University of Chicago since 1976. Her interests lie in language and cognitive development in children, especially the creation of language, and the role of gesture in communication and thinking. She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She was chair of the Linguistics and Language Sciences section at the AAAS. She has received numerous prestigious awards and fellowships, including the William James Award for her lifetime contribution to basic science from the Association for Psychological Science in 2015. In 2022, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Geneva. She is the founding editor of the journal Language Learning and Development (founded in 2004).

In 2024, Susan Goldin-Meadow was invited to Frankfurt by Cornelia Ebert, Professor of Linguistics/Semantics at Goethe University Frankfurt and Goethe Fellow at the Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften in Bad Homburg.

The interviewer

Dr. Anke Sauter, born in 1968, is a science communicator and an editor of Forschung Frankfurt.

sauter@pvw.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding