The fascinating world of p-adic geometry

Photo: amtitus/istockphoto

The world that mathematics professor Annette Werner is exploring seems strange to us, almost absurd: in it, different numbers are of the same magnitude, and circles have an infinite number of midpoints. She is conducting research in the field of p-adic geometry – a branch of modern algebra that has made rapid advances in recent decades.

If we want to tell someone how far one place is from another, we can do it in several ways: for example, we can express the linear distance in kilometers, in yards or in light years. However, we can also say how long it takes to get there on foot, by car or by public transport. Depending on which method and unit of measurement we choose, we obtain different values for the distance in question. It might even be the case that we are unable to convert these values intuitively into each other because the measurement systems are fundamentally different. For example, two places might be just a few kilometers apart, but the journey by bus and train nevertheless takes an eternity – in a case like this, the distance in kilometers is small, but it would take a long time when measured in terms of public transport. However, every single measurement method – whether linear, road or walking distance or distance with public transport – works and is legitimate.

Annette Werner has started exploring an unusual but equally plausible and consistent way of measuring distances. “You could say I’m just using a different ruler,” she says, yet her way of measuring changes the entire character of the world she is measuring. This might sound dramatic, but it is in fact quite normal: each method of quantifying distances also produces different concepts of “near” (small distances) and “far“ (large distances), like the differences between measuring by “linear distance” and “public transport”. What is meant by “near” and “far” in each case is essential to defining the character of a space. The “ruler” that Annette Werner uses in mathematics to measure the magnitude of numbers and that makes the world of numbers seem so unfamiliar and alien to outsiders is based on prime factorization.

Any natural number can be clearly factorized into powers of prime numbers, for example:

30 = 2 · 3 · 5

33 = 3 · 11

36 = 2² · 3²

75 = 3 · 5²

76 = 2² · 19

This method of prime factorization can now also be used for measuring magnitude. Instead of taking the ordinary value of the number (which is the standard “ruler”, as it were, for measuring numbers), we look at its factorization and ignore all but a certain factor called p, such as p = 3 or p = 907 or any other value. The reciprocal of the power of this factor p in the prime factorization of a number is known as the p-adic value of the number. Thus, p is simply written into the denominator as often as this prime number occurs as a factor in the prime factorization. It is a simple concept. Let’s calculate the p-adic value of the above numbers when p = 5:

|30| = 1/5

(because 5 occurs exactly once as a prime factor)

|33| = 1

(because 5 does not occur as a prime factor, and 50 = 1)

|36| = 1

(likewise)

|75| = 1/52 = 1/25

(because 5 occurs exactly twice as a prime factor)

|76| = 1 (see above)

If the prime number p = 3, the p-adic values of the above numbers are:

|30| = 1/3

|33| = 1/3

|36| = 1/32 = 1/9

|75| = 1/3

|76| = 1

This way of measuring the magnitude of a number seems bizarre: if, for example, p = 3, then the numbers 30, 33 and 75 are of equal magnitude, and 36 is smaller than 33. All this contradicts our understanding of numbers and magnitudes. Apart from that, however, there is nothing at all strange about the p-adic value. On the contrary, as Annette Werner explains: “We can show that the p-adic value works in principle in the same way as the notion of distance, which we use in our everyday lives.” This means that it is a technically non-contradictory method that also fulfils certain conditions which are useful for measuring length. Essentially, therefore, the p-adic value functions in the same way as other methods for measuring length. “Most people are content with the ordinary ruler,” says Werner with a smile, “but we mathematicians are not. This shows very nicely how we think. We ask ourselves what is generally behind the principle of ‘distance’ and ‘ruler’ and what the mechanisms are that all rulers and distances have in common.”

The concept of the p-adic value, that is, expressing the magnitude of a number by one of its prime factors p, not only works for natural numbers but can also be applied to fractions. Incidentally, what you choose as p is irrelevant because every choice leads to a world that works according to the same laws. “It makes no sense at all, for example, to look only at p = 17,” explains Annette Werner, “all p are the same for us.” That is why p-adic numbers and values are referred to using the abstract p instead of a specific number: the structure of the numbers and values remains the same, regardless of whether p = 11 or p = 599 or another prime number is chosen. Mathematicians consider all cases at the same time rather than specific situations by using p as a flexible placeholder.

There is even more to the p-adic world than an equivalent to our familiar fractions: just as the gaps between our classical fractions are filled by irrational numbers such as π, e or √2, the gaps between the p-adic fractions can also be filled so that a dense line of numbers results, very similar to the real numbers – except that here they are slightly different numbers, and distances are calculated differently here.

From these new numbers and distances, we now arrive at Annette Werner’s specialist field, p-adic geometry, by using these new numbers as a basis for geometric concepts. In a first step, we can analyze equations, for example, and examine the figures that solve the equations, exactly as we do with conventional real numbers. For example, the real equation x = y is solved by all points (x, y) in the two-dimensional coordinate system in which x and y are identical; these points form a straight line. The equation x2 + y2 = 1, on the other hand, produces a circle. Examining which equations describe which figures and which abstract properties of the equations are reflected in which properties of the corresponding figures is one of the classic challenges in geometry.

By contrast, p-adic numbers produce a different kind of geometry than the one we are accustomed to from experience because they behave differently, and this leads to curious results: in p-adic geometry, for example, each circle has an infinite number of midpoints. “You can’t imagine that,” says Annette Werner reassuringly, “but you don’t have to, you can examine it with mathematical methods.” We cannot begin to imagine an infinite number of midpoints, and it sounds absurd, but at the end of the day it is the clear and incontestable result of a simple calculation: the midpoint of a circle – in our geometry as well as in other geometries – is defined as the point that has the same distance from all points on the circumference, and with the p-adic way of measuring distances, all points inside the circle have the same distance from all points on the circumference. Thus, beyond all imagination, all points in the circle, no matter where they lie, are quite simply the midpoint.

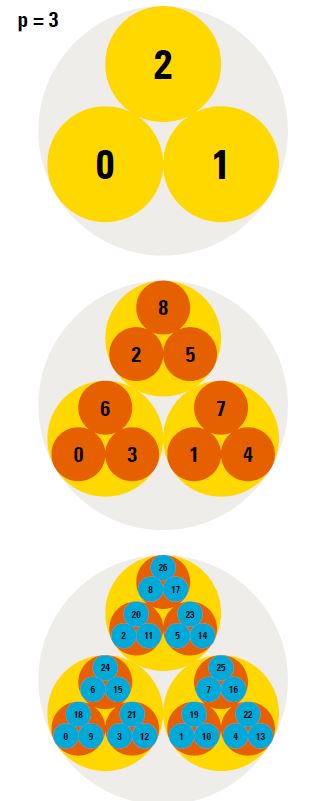

You can arrive at p-adic numbers through whole numbers that have the same remainder classes. If you divide natural numbers by 3, for example, the remainder is either 0, 1 or 2:

0 modulo 3 = 0

1 modulo 3 = 1

2 modulo 3 = 2

3 modulo 3 = 0

4 modulo 3 = 1

How to calculate “modulo 3” is explained, for example, at https://tinyurl.com/ModuloOperations All numbers that produce the same remainder after dividing by 3 (yellow circles in the top grey circle) are referred to as the remainder class.

The grey circle in the middle contains the remainder if you divide natural numbers by the second power of 3, i.e. 32 = 9: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 in the orange circles.

Three orange circles are in a yellow circle if the corresponding numbers have the same remainder class modulo 3, for example:

2 modulo 3 = 2

5 modulo 3 = 2

8 modulo 3 = 2

Therefore, in the top yellow circle (where previously only the 2 was) there are now smaller, orange circles with 2, 5 and 8, all of which have the remainder 2 modulo 3 – although they are different remainders of modulo 9.

The game continues with the third grey circle and the third prime power 33: if we look for remainders modulo 33 = 27, then each orange circle is divided again into three circles. 8, 17 and 26 are entered in the circle at the very top containing 8. These three numbers all have the remainder 8 modulo 9, but different remainders modulo 27. That is why they are in the same orange circle, but in different blue ones.

Another simple calculation, which students can also do as homework, shows that in the p-adic world each triangle has at least two sides of the same length, or in other words: triangles with three sides of different lengths cannot exist. “This all sounds strange,” admits Annette-Werner, “but that’s only because the words ‘triangle’ and ‘circle’ evoke images in our heads that are based on our experience, and these are specific cases that do not reflect the p-adic situation.”

Triangles with at least two equally long sides, circles with an infinite number of midpoints, large numbers with small values – from our everyday experience, all this might seem absurd to us, but the p-adic numbers form an orderly, plausible, regular world, within which everything is organized according to coherent and logical laws. What makes this world so peculiar for us is only that it is populated by numbers that we are not familiar with in our everyday lives, and that the rules which they are based on are also different from those we are accustomed to from the numbers we use every day.

Geometry is more than just investigating a formal equation and its set of solutions. For example, several equations can be analyzed together. We can also put a variable in a sum with an infinite number of summands and ask ourselves when and in what context this sum, which is nothing more than a formally expressed object, acquires a purposeful meaning, what properties it has, what it has in common with the infinite sums we know from the world of real numbers, and much more.

“I like to peel away the shell and get to the kernel,” says Annette Werner, “for example, I take a concept and see whether it works in a different context in the same way, or somehow differently. Why? Because that’s how a mathematician’s brain works!” She explains: “We ask ourselves what language we can use to understand an object and what it means in other languages.” Annette Werner has recently succeeded in transferring parts of what is known as the Simpson correspondence to the p-adic world. This work is concerned with mathematical structures called Higgs bundles and how they interact with the topology of manifolds.

A manifold is an abstract generalization of a surface, for instance a pretzel or a bagel. Topology is the theory of spatial objects and their tear-free deformations. Imagine, for example, that the pretzel is made of rubber and you pull on the loops without tearing them. The pretzel then changes shape, but the number of holes remains the same. Conserved quantities, such as the number of holes, which do not depend on the specific shape of an object but reveal something about its basic structure, are of particular interest in mathematical research. After all, Higgs bundles are related to the Higgs boson, the famous elementary particle, and two scientists were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013 for its theoretical investigation (after experimental physics research at the CERN particle accelerator in Geneva in 2012 had succeeded in providing experimental evidence that this particle actually exists).

Annette Werner has transferred this concept – the interaction of Higgs bundles with manifolds – to p-adic geometry. “I’m investigating the p-adic ‘cousins’ of these Higgs bundles to find out what they can tell us about the geometry and topology they encounter there.” In her work, Werner has used the theory of perfectoid spaces developed by the mathematician Peter Scholze at the University of Bonn, among other theories. In 2018, Scholze was awarded the Fields Medal for his work, one of the most prestigious prizes in the field and known also as the “Nobel Prize of Mathematics”. “Getting used to these methods is hard work when you are no longer young,” recalls Annette Werner, “but I can use these methods to illuminate and prove things that were previously a closed book to me.”

Despite the close relationship to the famous Higgs boson, Annette Werner believes that her research is unlikely to interest anyone at CERN. After all, it’s fundamental research. “It doesn’t bother me whether what I’ve discovered can be applied to a specific problem, that’s not what motivates me. But I know that I’m laying a solid foundation for our science with my work, and we’ll need this sooner or later to solve concrete problems in the future.”

IN A NUTSHELL

- p-adic numbers are another way of measuring distances. They are based on the factorization of a number into prime numbers, that is, numbers that are only divisible by themselves or 1.

- Like real numbers, p-adic numbers can also be used to calculate geometric figures. However, we are unable to imagine them, and they have seemingly bizarre properties.

- p-adic geometry is a tool for modern number theory, which in turn is the basis for encryption algorithms.

As one of the principal investigators, Annette Werner is also working as a scientist within the Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio 326 “Geometry and Arithmetic of Uniformized Structures” (many of the participants probably had to get used to the acronym GAUS at first because the name of Gauss the mathematician sounds the same but is written differently). The center aims to answer structural questions in geometry and arithmetic and to find fundamental connections between concepts such as modular spaces, automorphic forms, Galois representations and cohomological structures. GAUS is coordinated by Goethe University Frankfurt and has been awarded funds of €9.2m by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

“Research in geometry is, of course, far from what we learn about geometry at school and what we are capable of imagining,” says Annette Werner, “p-adic geometry is, for example, a helpful tool for modern number theory.” Knowing how numbers function, what properties they have and how to work with them has become indispensable for the digitally networked world: every encryption algorithm, from email to online banking, works with objects and methods from number theory. p-adic numbers and values have also found a place in the abstract toolbox used to examine and work with numbers: “Investigating the p-adic values of numbers provides us with completely different and often surprisingly useful information about structures in the numbers,” explains Annette Werner.

About

Annette Werner, born in 1966, studied German studies, musicology and journalism at the University of Münster before discovering her interest in mathematics. After completing her doctoral degree, she worked at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in Bonn and was professor at the University of Siegen and the University of Stuttgart before taking up a professorship at Goethe University Frankfurt in 2007. She was awarded a Heisenberg fellowship by the German Research Foundation and was a visiting professor at the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute in Berkeley, California. Her areas of expertise are arithmetic algebraic geometry, non-Archimedean analytical geometry and tropical geometry. Annette Werner is mother to two adult children and a principal investigator in CFC/Transregio 326 “Geometry and Arithmetic of Uniformized Structures”.

The author

Aeneas Rooch, born in 1983, studied mathematics and physics and earned his doctoral degree in probability theory. He works as a science journalist, as well as assisting researchers with lectures and science communication.

https://rooch.de