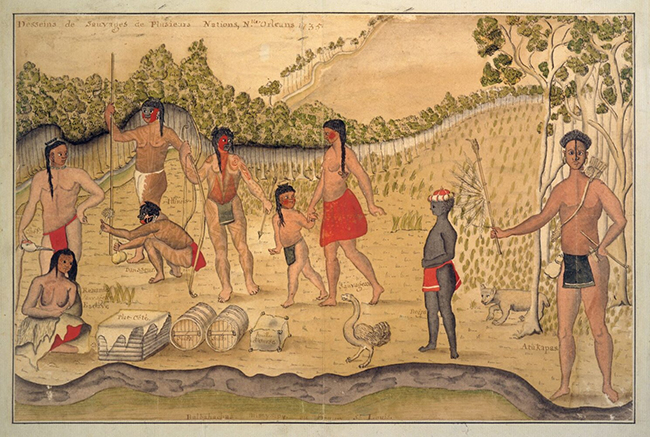

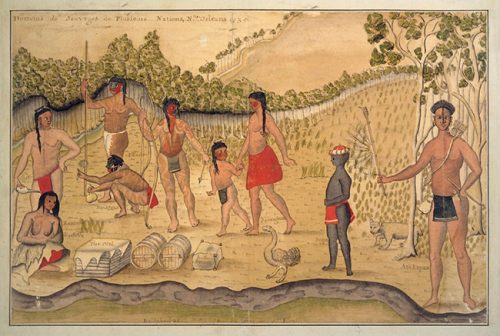

How French missionaries encountered Native Americans in French Louisiana

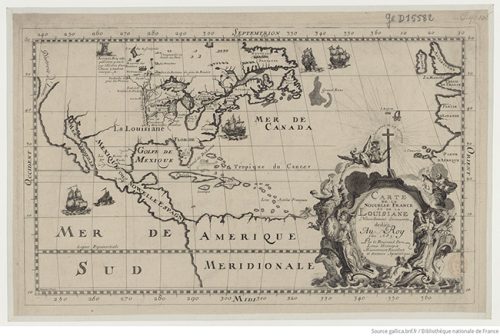

Illustration: ©gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France

Tasked with proselytizing the indigenous population, French clerics traveled to the American South. But communication was not easy and sometimes failed entirely. The numerous reports about these encounters circulating in Europe showed that this interaction sometimes disrupted the missionaries’ self-image.

Illustration: ©wikimedia commons

At the end of the 17th century, the Capuchin monk Louis Hennepin reported extensively on his efforts to convert the inhabitants of the newly founded French colony of Louisiana to the Christian faith. To do this, they first, of course, had to understand him. The indigenous population in the region, which stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes of North America, spoke different languages. To help them communicate among themselves, they used interpreters, as Hennepin observed with great interest. He himself doubted, however, whether he had sufficient language skills to teach them and convey the divine message. He describes how he ran around a room to find the word for “running” and note it down in a dictionary. Admittedly, such basic knowledge did not enable him to appear immediately as an expert in transcendental truths. So as not to awaken any mistrust, he hid when he wanted to pray, but this only served to increase suspicion rather than mitigate it. To explain why God had sent him to the forests of New France, he told the Native Americans that the “captain” in heaven had instructed him to do so. But they nevertheless assumed that his books contained demons, and communication problems made his work difficult.

IN A NUTSHELL

- The French missionaries played a central role in colonial expansion in the American South. They spread the Christian faith and gathered knowledge about the land, its flora, fauna and the Native Americans.

- Communication between French missionaries and the indigenous population was often difficult and full of misunderstandings. Language barriers and cultural differences meant that attempts to teach the Christian faith repeatedly failed.

- The missionaries’ reports often described the indigenous population as “noble savages” who could be converted and civilized by the French. At the same time, they emphasized the need for constant guidance and supervision.

- Some missionaries questioned whether their work was effective and perceived the indigenous people as self-confident individuals unwilling to be proselytized. Ultimately, this differentiated standpoint also challenged the Eurocentric worldview.

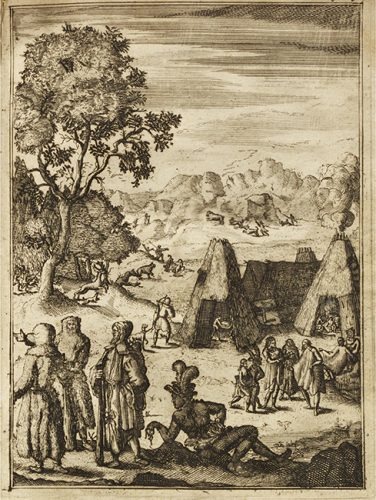

Missionaries in the French colonies

Illustration: ©Openlibrary.org

Missionaries were involved in the colonial expansion of French territories from the very outset. Their role was supposed to ensure that the new subjects were bound to the empire through the Christian faith, and they had to take care of mediation and translation. The missionaries learned indigenous languages and tested various teaching methods that were not dissimilar to European ones. After all, they had practiced dealing with the uneducated laity beforehand, for example in Britanny. The clergy’s activities were steered from France, but also by the bishop of New France in Quebec – so in both cases across very long distances. There were constant arguments between the management of the French trading company Compagnie des Indes and the churchmen about who was responsible for what, with each side accusing the other of moral transgressions: The merchants were criticized for their extravagant lifestyle and the clerics for being too close to the Native Americans.

After their success in proselytizing the indigenous population had remained rather modest, the missionaries attended instead to the French settlers and their spiritual welfare. In the first instance, these were convicts, prostitutes and outcast family members who had been forcibly resettled. Toilsome work in the fields, however, was delegated to African slaves trafficked mainly from Senegambia (now Senegal) by the Compagnie des Indes. The newly founded colony remained first and foremost a business venture distinguished by adventurous speculation.

Imperial knowledge

The traveling missionaries were anxious to send regular reports on their successes back to their homeland. This was directly connected to their self-image and the need to find support – including funds – for their missionary work. At the same time, they fervently gathered all available knowledge about the climatic conditions, flora, fauna and the “nations” they came across, contributing to a natural history that became part of the conquest during the 17th and 18th centuries. From a theological perspective, this accumulation of knowledge was easy to justify. After all, they were convinced that they were reading from the book of nature as intended by God. This also encompassed knowledge of natural healing. The nomenclature was based on tradition and direct visual impressions, as well as practical applications. Even if this knowledge was not yet classified according to a universally structured system, such as that devised by Linnaeus, it was nevertheless knowledge conducive to the imperial effort. Literary scholar Mary Louise Pratt refers to this as knowledge through “imperial eyes”: It was the knowledge of rulers, which circulated in numerous translations and many publications throughout Europe. It seemed useful for dealing with the population of the New World, helped expand European hegemony and shaped colonial plans in the further course of history. At the same time, it can be assumed that “indigenous knowledge” contributed to building natural history expertise in the imperial world (Lachenicht, 2023). Tracing the contribution of indigenous stakeholders remains a topic for future research.

Dangerous rosaries

In the literature on the natural history of New France, missionaries wrote detailed descriptions of the population they sought to proselytize. The exoticized Sauvages (or, as they were called in the reports written in Latin, the gens silvestris, sylvicolae or sylvatici – meaning people of the woods) were said to have the best prerequisites for converting to Christianity. What they lacked was cultus (i.e. knowledge of Christian practices), but not the ability to achieve perfection. With corresponding effort, the noble savage, who was close to nature, could become a better Frenchman. Through their contact with the French, however, many had become accustomed to new norms, which could already be seen from the fact that they wore fur when they went to church. Nevertheless, the missionaries were convinced that they needed constant guidance and supervision, summoning them regularly to mass and catechism at the mission station, where they were expected to learn and repeat what they had been taught. Unlike the officials of the French Empire, the Jesuit priest and missionary Gabriel Marest had no objection to French settlers marrying indigenous women. After all, he had observed that the women working in the countryside were particularly receptive to the truths of the Gospel. In his opinion, far more important than origin and ancestry – typical of the differentiation between peoples in the early modern period, i.e. before race became a biological category – was socialization. That is why his greatest fear was that a libertine or renegade might stray into the mission station, as the negative example of such a Frenchman could wreck his missionary work. In his report published in 1715, Marest gives a detailed account of the customs and practices of the Native Americans and peppers them with anecdotes about misunderstandings: He describes, for example, how a “medicine man” (whom he calls a charlatan) felt threatened by a rosary that a newly converted woman held in her hands and supposedly tried to defend himself with a rifle (Lettres édifiantes et curieuses 1715, 304).

Competing interpretations

Over the course of the 18th century European scholars gradually began to ponder whether the missionaries might also be prone to misunderstandings. This thinking was based not least on differences in reporting. Hennepin, mentioned above, does not give the impression that proselytization was always successful, as the indigenous people often proved “indifferent” to attempts to convert them to Catholicism. In addition, he portrays them as individuals who act with self-confidence, possess medical skills and are capable of defending themselves with arguments when the European cleric attempts to impose his worldview on them. However, Hennepin’s nuanced view shows him to be a clergyman who has hardly adjusted either and who sought not least to set himself apart from a rival order, the Jesuits, and their reporting practices. Most other sources are dominated by the image of the fundamentally good, civilization-savvy savage, who is clearly distinguished

from the Black slave. However, the descriptions handed down of the customs and traditions, but also of the physical appearance of the Sauvages, often allow for further interpretations beyond the binary constellation of the rulers and the ruled – even to the point of imagining that the Frenchmen could become wild (cf. White, 2013).

Illustration: ©gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France

Knowledge about people

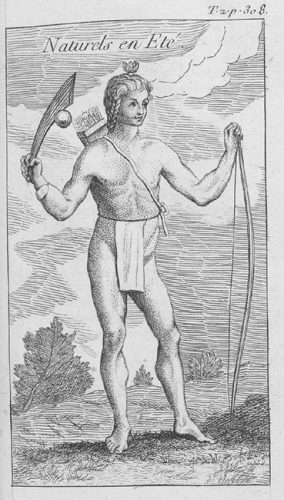

A significant finding emerging from recent research is the observation that the French clergymen, in their contact with other cultures, apparently felt that their masculinity was challenged. They felt obliged to justify their celibate lifestyle and had to adapt to unfamiliar climatic and hygienic conditions. Hennepin praises the benefits of a steam bath that the Native Americans prepared for him and which he found therapeutic, while renegotiating the boundaries of morality at the same time. Naked bodies were altogether a constant provocation for Hennepin (see for the general context Fischer/Tippelskirch, 2021). The fact that he was also confronted, in his attempts to learn the language of the Illiniwek, with words for body parts that he did not even dare to think about made any kind of linguistic understanding additionally complicated. Religious knowledge did not really prove helpful in the contact zone, but instead often made communication more difficult, as certain topics were off-limits in everyday conversation and abstract concepts seemed difficult to translate.

On the basis of the many different reports, scholars in the 18th century attempted to compare indigenous customs with ones from antiquity. In so doing, they positioned the rites observed in the New World in a – by no means unbiased – history of human development, seeking to make the unfamiliar understandable as an early form of Christian practices. However, the awareness that social and in particular religious practices were always dependent on time and place ultimately led to a relativization of cultural hierarchies.

The author

Xenia von Tippelskirch, born in 1971, has been a professor at the Institute of History, Goethe University Frankfurt, and the co-director of the Institut franco-allemand de sciences historiques et sociales (IFRA-SHS) since December 2022. She studied in Freiburg and Pavia, earned her doctoral degree at the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence and was a Marie Curie Fellow at EHESS (School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) in Paris. She has taught in Bochum, Tübingen, Amiens, Toulouse and Kassel and was junior professor at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her work and research focus on the history of religion in the early modern period and the Renaissance, particularly in France, the Holy Roman Empire and Italy. She publishes in French, English, Italian and German on the history of piety, religious separatism, mystical movements, and the history of monasteries and the Inquisition. She is interested in the cultural, gender and body history of the early modern period, with a particular focus on material and written culture as well as knowledge transfer. She is currently studying the history of Catholic missions to French Louisiana.

x.vontippelskirch@em.uni-frankfurt.de

Literature

Hennepin, Louis: Description de la Louisiane, nouvellement decouverte au Sud Ouest de la Nouvelle France, Par ordre du Roy, Paris 1683.

Marest, Gabriel: Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, Paris 1715.

Fischer, Elisabeth/von Tippelskirch, Xenia (Hrsg.): Bodies in Early Modern Religious Dissent: Naked, Veiled, Vilified, Worshiped, New York 2021.

Gay, Jean-Pascal/Mostaccio, Silvia/Tricou, Josselin (Hrsg.): Masculinités sacerdotales, Approches historiques et apports sociologiques, Turnhout 2022.

Lachenicht, Susanne: Indigenous Knowledge, in: Oxford Bibliographies in »Atlantic History«, 2023. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0376

Pratt, Mary Louise: Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, London 1992.

Vidal, Cécile: Caribbean New Orleans: Empire, Race, and the Making of a Slave Society, Chapel Hill 2019.

White, Sophie: Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians. Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana, Philadelphia 2013.

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding