On language death and lost perspectives

1000 Sprachen – 1000 Welten. Wie sprachliche Vielfalt unser Menschsein prägt

Frankfurt am Main,

Westend Verlag 2025,

ISBN 9783864894817,

bound edition, 320 pages, €26

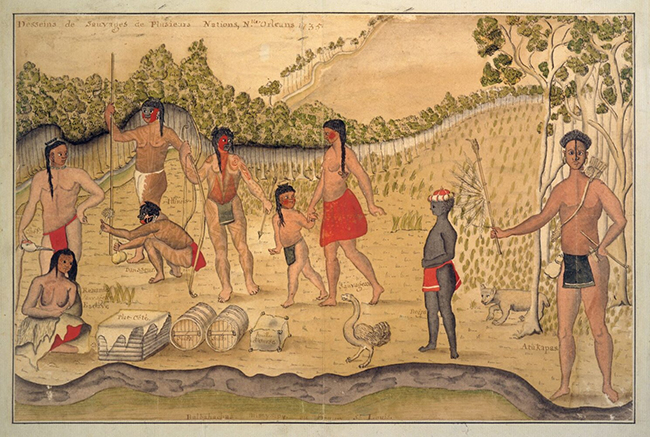

In the course of globalization, humanity is increasingly pushing in the same linguistic direction – a phenomenon that is causing some languages to die out. Global harmonization is regarded as progress, above all in the West. In his book “A Myriad of Tongues: How Languages Reveal Differences in How We Think”, the American cognitive scientist Caleb Everett (University of Miami) illuminates how language expresses a linguistic community’s view of the world and why preserving linguistic diversity is so important for cultural diversity on our planet.

Everett takes his readers on a journey through various themes, such as sensory impressions or time and space, using examples from different languages to explain similarities and differences in the perspectives of linguistic communities. At the end of each chapter, he presents

his conclusions, often comparing smaller cultures with “WEIRD societies” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) – for the Western book reviewer a frequent eyeopener.

Language is closely connected with how people think, how they count and how they orientate themselves spatially –and how they understand their relationship to nature. Everett illustrates this using indigenous languages in the Amazon, which have no abstract numbers. Even though these communities do not count in the same way as we do, everyday life and trade function equally as well – just differently.

Spatial orientation, too, is articulated differently depending on the language: While we have words such as “right” and “left” to locate something in relation to our own position and another point in space, the Guugu Yimithirr community in Australia uses solely the points of the compass for orientation – even in enclosed spaces. This constant reference to geographical position obliges the members of that linguistic community to acquaint themselves in far greater detail with the directions of a compass.

In many languages, there is no grammatical distinction between the future and the present – which can also influence the way people think about time. In other languages, in turn, possession is not expressed as something individual but rather relational: Instead of “my house”, it is “the house that is connected to me”.

Knowledge of other languages and ways of thinking upends our worldview of our own culture; we become increasingly aware of this as we read. It is possible, we realize, to see and treat things quite differently. Taking seriously the unfamiliar aspects of another culture and society where a different language is spoken can undoubtedly disclose new perspectives.

The author

Joana Gerheim, born in 1998, is a linguistics student at Goethe University Frankfurt, where she also works as a student assistant in the Public Relations Office.

gerheim@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding