Language education through Latin and the history of language

What is the difference between freedom and liberty? What does the parallel existence of such terms reveal about the history not only of this one language but also that of a whole continent? Looking at the roots of Europe’s linguistic history can impart a lot of cultural knowledge and make it easier to learn foreign languages.

Foto: sylv1rob1/Shutterstock

Rendez-nous la statue de la Liberté! – This was the pithy statement with which French MEP Raphaël Glucksmann was quoted in March 2025, when in view of US policies clearly no longer in sync with liberal European values he demanded the return of the Statue of Liberty. The colossal monument in New York Harbor, sculpted by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi in the neoclassical style, was a gift from France to the United States to mark the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Soon after its inauguration in 1886, it already became a national symbol. Indeed, the statue’s very name is symbolic: La Liberté éclairant le monde alludes not only to Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting of the July Revolution, but, above all, to the metaphor of light in the Enlightenment (éclairer, to enlighten), in whose intellectual history America’s independence and democracy are contextualized and which is reflected in the torchbearer’s flame of progress. Consequently, the famous statue is called “Liberty enlightening the world” in English. But how did that come about? Shouldn’t it be “freedom” and not “liberty”?

Language as the mirror of history

From an etymological perspective, it is easy to spot the French word “liberté” in “liberty”, but both are also derived from the Latin root libertas, which is also the name of the Roman goddess of freedom – this small detail is also relevant, as it leads back to the feminine gender of mythical personification in the Roman tradition of allegorical representations. Due to its historical development, English bears traces of both Romance and Germanic languages, even though it originally belongs to the Germanic language family. Like freedom and liberty, nuanced synonyms are sometimes used across all parts of speech, which on the one hand can be traced back to Old English etyma and on the other hand point to linguistic influences from French or Latin: fall/autumn, mankind/humanity, trade/commerce, unbelievable/incredible, to go in/to enter, to shut/to close, etc. Only in the 14th century did English gradually start to prevail over French, which had been the court language for four centuries since the Battle of Hastings in 1066 – words such as cherry, hostel and beef originate from this Middle English era under Norman rule. Like these examples, around 60 percent of English vocabulary today is of Romance-Latin origin, and only around 20 percent can be traced back to Old English. The French linguist Bernard Cerquiglini concludes from this, rather tongue in cheek, that the English language does not exist at all but is merely badly pronounced French. “La langue anglaise n’existe pas. C’est du français mal prononcé” (see bibliography).

These examples show how productive language contact has been in the course of history. In fact, linguistic influence was not limited to the lexical level (i.e. word level). There are also interesting aspects to discover in other linguistic structures. One, dealing with the history of language, also opens one’s eyes to cultural and historical discoveries that allow for drawing far more than just linguistic conclusions.

French – the lingua franca of the 17th century

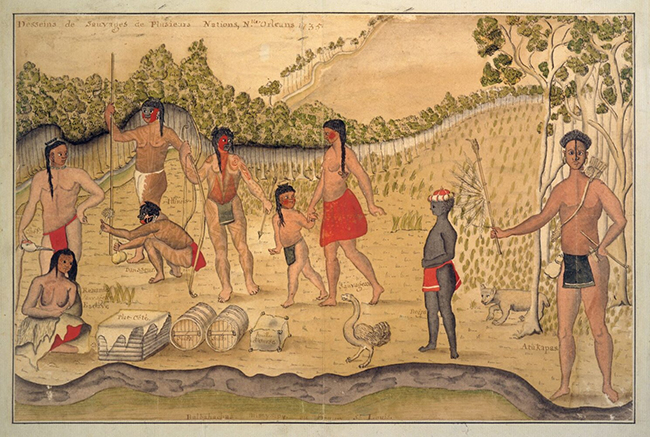

The Romance languages are particularly interconnected. From the 17th century onward, French embarked on its triumphal march as the lingua franca of Europe with an emphatic claim to universality, becoming a world language in the course of European colonization. It only lost its unique position worldwide after the First World War: The Treaty of Versailles was not written solely in French, but also in English.

A booster for foreign language teaching

Romance Multilingualism in Teaching” was the title of a seminar held in the 2024/25 Winter Semester as part of the collaboration between the Rhine-Main Universities (RMU). It focused on interlingual comparison, the history of language and the Latin origins of the Romance languages in the context of foreign language learning. Students studying Italian, Portuguese, French, Spanish and Latin as part of their teaching degrees at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and Goethe University Frankfurt met alternately at the two locations and analyzed intercomprehensible strategies for language learning and their didactic potential, especially for reading comprehension, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar and language awareness. Via Latin, they were able to gain insights into European linguistic and cultural history. An international conference in February 2025, where students were invited to present the results of their analyses and take part in the discussion, rounded off the course. Professor Sylvia Thiele (Mainz) and Professor Roland Ißler (Frankfurt) intend to continue their collaboration in the coming years; among the activities planned are an RMU certificate in multilingualism.

A language’s prestige is also closely linked to its literary significance. In 14th century England, Geoffrey Chaucer developed his own distinct literary language, long after France’s first literary heyday had passed: The first texts in French date back to the 9th century: In the form of the chansons de geste (heroic epics) and courtly novels in the north and the Occitan poetry of the troubadours in the south, a cultural zenith had already been reached in the Medieval French that shone throughout Europe. In Chaucer’s time, French humanism entered a phase of linguistic expansion and re-Latinization, as continuation of the rich linguistic tradition of the past. Alongside words inherited as a result of language change (la chose, froid, livrer, droit = in Latin causa, frigidum, liberare, directum), there were scholarly borrowings (la cause, frigide, libérer, direct), which, particularly to this day, can be easily traced from one language to another and are often also internationalisms.

While Italian orthography, for example, was modernized at around the same time and became more phonemic, that is, oriented to pronunciation, France maintained its conservative etymological spelling system, which is, incidentally, also characteristic of English (to doubt = in Latin dubitare). Modernization trends in Spanish date back as far as the 13th century, under Alfonso the Wise. To this day, for example, the French words la physique, l’ophthalmologue and the Italian words la fisica, l’oftalmologo or the Spanish words la física, el oftalmólogo are still used. The orthographic complexity – the French graphemes au, aud, auds, ault, aulx, aut, auts, aux, eau, eaud, eaux, haut, hauts, ho, o, ô, od, ods, oh, os, ot and ots differ only in spelling, not in pronunciation – nevertheless guarantees the recognizable affiliation of French with the Romance language family.

The continuum of language change

As linguistics teaches us, language is a phenomenon subject to constant change. A human lifetime is usually too short to see this development clearly; even native speakers are only aware of it in areas such as youth slang, or technical jargon, which constantly adapt to technological progress. However, the significance of language change should not be underestimated. The comparative study of foreign languages is a worthwhile endeavor, not only vis-à-vis vocabulary but also at the structural level. Frankfurt University’s namesake too was aware of the fact that through such study reflective approaches emerge. As Goethe aptly put it: “Those who know nothing of foreign languages, know nothing of their own.”

Therefore, knowledge of the linguistic historical developments can also be advantageous in foreign language teaching. Acquiring such knowledge gives learners of a foreign language more detailed explanations of and categorical insights into, the change in formal linguistic structures in orthography and phonology, morphology and syntax, semantics and word formation. It potentially eases access to contemporary language and makes a substantial contribution to language awareness.

Although such language awareness is a skill that current educational standards demand, the curricular restructuring it has partly caused has paradoxically ousted historical linguistics from university syllabuses. The relation to contemporary language seems to have lost its importance because the advantage of knowing the history of language is sometimes only apparent at second glance. Since the Bologna Process, its part in modern philology has steadily decreased. Against this background, the question of the potential offered by language change phenomena for foreign language teaching and their relevance for teaching and teacher training also bears weight in terms of education policy. Comparable, for example, with the pressure to justify itself that Latin teaching is repeatedly subjected to – the Latinum language exam is no longer a university entry requirement, not even for Romance Studies – the history of language is increasingly being forced onto the defensive. However, as part of European cultural heritage, both are important testimony to cultural and historical connections, providing insights into the interconnections between languages.

Knowledge of the history of language contributes not only to our understanding of how individual languages have developed and the changes they have undergone over time, it also helps us expand our vocabulary and understand foreign words more easily. The emergence of French expressions, for example, or the prevalence of Anglicisms in other European languages testify to the historical significance of the countries of origin in certain periods of European history and, to this day, reveal a lot about the cultural transfer that caters to our European identity. History of language and cultural history are closely linked, which enables a deeper understanding of cultural contexts (such as the derivation of the names of the days of the week and the months in European languages). Knowledge of grammatical changes over the course of history can even help us to understand better, comprehend and deduce current rules by ourselves; such knowledge facilitates the reading and understanding not only of historical texts, but also improves our understanding of modern linguistic diversity.

Latin – the beauty of an old language

Closely connected to the history of language is Latin, which is the structural origin and basis of many European languages, not just Romance ones. Knowledge of Latin grammar can make

it easier to understand the grammar of new languages; there are reasons why Latin also provides a metalanguage for dealing with grammar itself. Many scientific or technical terms and foreign words are easily derivable from Latin. It is often argued that studying Latin fosters logical thinking and analytical skills that are helpful for learning other languages. However, learning Latin is certainly a worthwhile endeavor simply for the beauty of the language itself and its literary radiance. Romance literature and philosophy are rich in works of fascinating timelessness, which – not by chance – have in turn shaped modern literature. The Latin language thus enables a deeper insight into Europe’s cultural heritage. Often, cultural and historical connections really become recognizable in the light of linguistic structures and link the present with the far behind left past. Without going on far journeys, we can find traces of ancient Rome there where we are less conscious of it: in our languages. While stone monuments such as Roman aqueducts or amphitheaters loom large before us as architectural relics of the Romans, we are also surrounded, without constantly thinking about it, by linguistic monuments that we carry around with us in our vocabulary and linguistic knowledge.

Structural knowledge simplifies language learning

While comparing languages, similarities and differences come to light that make it easier to learn new languages; learners can transfer their knowledge of languages they have already learnt to the languages still foreign to them. This applies not only for grammatical structures, which are often easier to understand by comparing them, but also for vocabulary. Comparing sound systems can make it easier to learn pronunciation but also to master the orthography of new languages: Knowing that accents were introduced into the French language by humanist book printers in the 16th century, for example, the spelling, often perceived as erratic, suddenly discloses a logical system, as the accent circonflexe mostly replaces a silent -s- before a vowel that has been retained in other languages (French la feste = la fête, Italian la festa, Spanish la fiesta, German Fest, etc.; similarly: l’hôtel hostel; la forêt forest, German Forst; French la guêpe, German Wespe). Recognizing the similarities in language families can make the learning of related languages much easier. Finally, comparing languages fosters intercultural communication and helps to avoid culture-related misunderstandings.

Learning foreign languages means freedom, as it helps reaching beyond boundaries and linguistic barriers. Linguistic diversity is one of the wealths of our planet and at our fingertips as an opulent treasure of the European cultural community. “Multilingualism means that our thoughts are not attached to a particular language, not stuck to its words,” as linguist Mario Wandruszka said. “Our multilingualism is the linguistic scope of our intellectual freedom.” It

is therefore a logical consequence that Lady Liberty makes reference to this in her name and lives up to it by holding the torch high and in an enlightened manner to honor it, even in turbulent times.

The author

Roland Ißler, born in 1977, is Professor of Romance Language Didactics and Transcultural Learning with a focus on Literary Didactics at the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Goethe University Frankfurt, since February 2023. He studied Romance languages as well as French, Italian and German philology in Greifswald, Clermont-Ferrand, Münster and Bochum, and received the Prix Germaine de Staël from the French Embassy for his doctoral dissertation on myth reception in France, Italy and Spain, which he submitted at the University of Bonn. He worked at the University of Bonn as a research associate, then later as a junior professor and academic advisor for Romance literature and didactics. Substitute professorships took him to Bochum, Duisburg/Essen, and finally Frankfurt. His main research interests are Romance literature, theory and didactics, cultural and aesthetic education, multilingualism and teacher training. He is head of the Romance Studies subproject in the collaborative project ViFoNet (video-based training modules for digitally supported teaching) funded by the Federal Ministry of Research, which includes AI and teaching research.

issler@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding

Literature

Cerquiglini, Bernard:

La langue anglaise n’existe pas. C’est du français mal prononcé, Gallimard

(folio, 704), Paris, 2024.

Grzega, Joachim: Europas Sprachen im Wandel der Zeit. Eine Entdeckungsreise, Stauffenburg, Tübingen, 2012.

Ißler, Roland: “Keine Angst vor dem accent circonflexe! Zum fremdsprachendidaktischen Potential von Sprachgeschichte und Sprachwandelerscheinungen im Fach Französisch. Ein Plädoyer für die Einheit von Fachwissenschaft und Fachdidaktik in der universitären Lehrerbildung”, in: Ißler, Roland/Kaenders, Rainer/Stomporowski, Stephan (eds.): Fachkulturen in der Lehrerbildung weiterdenken, V&R unipress (Wissenschaft und Lehrerbildung, 8), Göttingen, 2022, p. 105-143.

Janson, Tore: Latein. Die Erfolgsgeschichte einer Sprache, translated into German by Johannes Kramer, Buske, Hamburg, 2002.

Klabunde, Ralf/Mihatsch, Wiltrud/Dipper, Stefanie (eds.): Linguistik im Sprachvergleich. Germanistik – Romanistik – Anglistik, Metzler, Berlin/Heidelberg, 2022.

Wandruszka, Mario:

Die Mehrsprachigkeit des Menschen,

Piper, Munich, 1979.