How the brain turns sound waves into language

Photos: Uwe Dettmar

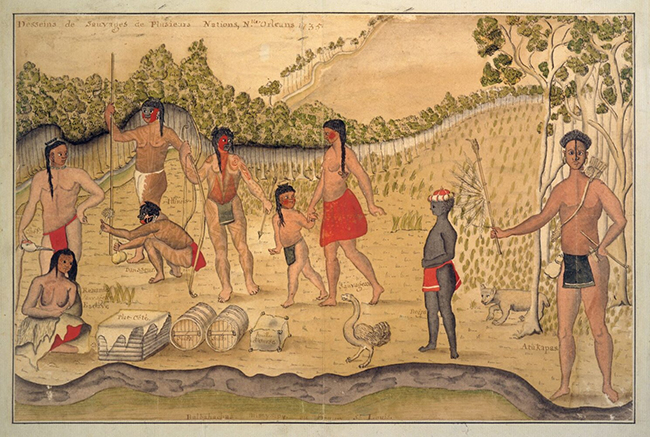

A brain tumor forces patients and doctors to make difficult decisions: How much of it can be removed, and how great is the threat that essential functions such as speech will be impaired afterwards? Neurologist Christian Kell attends to patients before and during such brain operations, which also present an opportunity for him to learn what happens in our brain when we speak. This helps him in his research, which focuses on understanding how the left and right hemispheres of the brain work together and what is different in people who stutter.

Initially, it sounds truly frightening: an operation on my brain while I am fully conscious. But most patients who undergo such an “awake craniotomy” with Dr. Christian Kell at their side say afterwards: “If a second operation were necessary, I would do it again.” The reason for such an operation is usually very serious: The person concerned has a brain tumor, a glioma, and support cells surrounding the brain’s nerve cells are beginning to proliferate. The aim is for the neurosurgeons to remove as much tumor tissue as possible, but there is a risk that brain functions that are still intact will be lost as a result of the operation. If such a tumor is located near a center important for speech or motor function, surgeons often seek to conduct an awake craniotomy. During such surgery, the patient remains conscious so that essential brain functions are preserved, while nevertheless removing as many tumor cells as possible.

“Together with my colleagues, the neurosurgeons, I discuss with patients about to undergo this type of surgery what is important to them and what limitations they could come to terms with,” says Christian Kell. “If someone is a musician, for example, and does not want to lose their talent for music, the surgeon will try to take this into account during the operation,” says Kell. “However, the chances of recovery are greater if the tumor is removed as completely as possible.” Most patients are willing to accept minor limitations such as difficulty finding words. “Almost everyone is familiar with that, and it is something you can work around in everyday life.”

Language tests with brain exposed

Photo: Uwe Dettmar

Such discussions with Kell prior to surgery are important so that the patient does not have to make any spontaneous decisions later in the operating theater and can bear having their brain operated on while fully conscious. Kell: “I personally wouldn’t be a good candidate for an awake craniotomy. I used to find even visits to the dentist extremely stressful. That’s why it’s great for me now to prepare patients like this and accompany them during the operation so they get through it successfully. We make sure the atmosphere is as relaxed as possible and that the patient is distracted. For example, we like to joke with the patient at our expense, such as the fact that I know nothing about soccer.”

For the operation, the patient’s head is secured in place and their skull opened under general anesthetic. Before the surgeons start to remove the tumor, the patient is brought round. This is because the neurosurgeon team led by Professor Marcus Czabanka and Professor Marie-Therese Forster needs the patient’s help to create a functional map of their brain, which varies slightly from person to person. By means of electrodes that emit mild electrical impulses, Professor Forster temporarily switches off areas of the brain surrounding the tumor, and then Kell and his team conduct tests to see what the patient is no longer capable of doing. The patient senses neither the electrical impulses nor the removal of the tumor, as the brain itself does not feel pain.

If the patient has given their prior consent, Kell’s team of neuroscientists then conducts a few more tests to gain a better understanding of how the brain processes language. This involves the patient remembering a sentence and then repeating it, for example, “The bear is threatening our village” or “There is a cake in the oven”.

Sentences first form in the brain

Photo: SeventyFour/Shutterstock

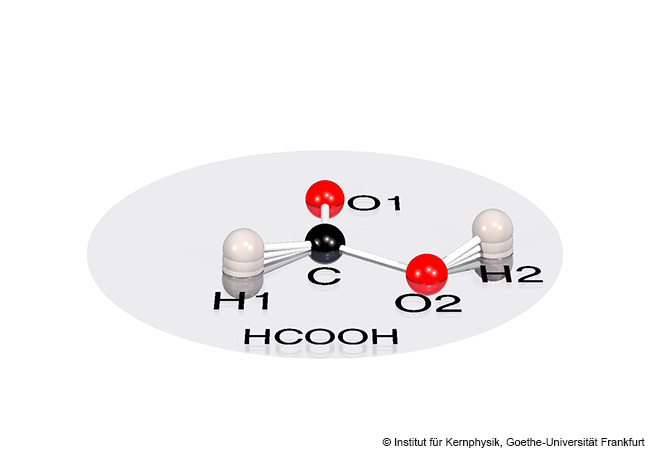

For the brain, a spoken sentence is initially just a stream of impulses from the auditory nerve that are triggered by sound waves. To further analyze these impulses, the brain divides this stream into units. The units are primarily syllables because these are rhythmically and acoustically distinctive. Where a word begins and ends is not acoustically clear. The brain only creates sentence structures such as syntax on the basis of its years of experience with language.

Brain signals reveal how this happens, as Kell explains: “We were able to read the syntactic structure of sentences from the signals, and this not only while the patient was hearing or repeating the sentence but also at times when they were holding the sentence in their short-term memory.” The brain stores the sentence heard as a temporal pattern, that is, in the form of rhythmic electrical activity known as neural oscillations. The patient can then reproduce the sentence from memory.

Syntax is not, however, generated and stored in one specific place in the brain. Rather, information about syntax is distributed across several brain regions and stored in a network. That is why individual brain regions can be surgically removed without the patient having problems forming (and repeating) sentences afterwards – provided that certain critical nodes in the network remain intact.

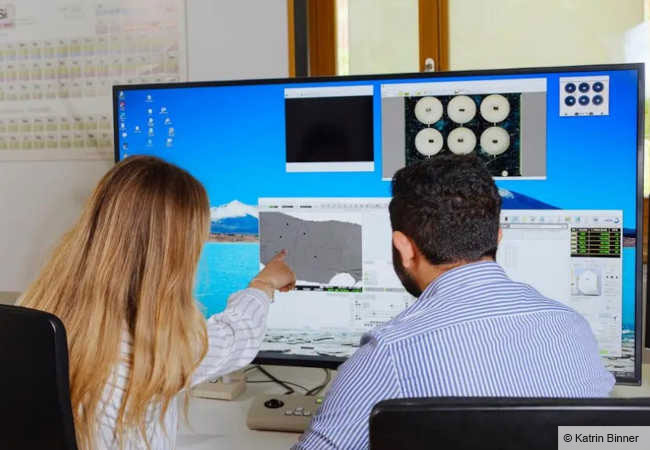

Brainpool

Cooperative Brain Imaging Center (CoBIC) is a collaboration between Goethe University Frankfurt, the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics and the Ernst Strüngmann Institute for Neuroscience. Its centerpiece is a new building that was officially opened in 2025 on Goethe University’s Niederrad Campus. CoBIC offers researchers from various disciplines direct access to numerous cutting-edge technologies, enabling them to gain a better understanding of how the brain works and develop innovative therapies for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Among other equipment, CoBIC has three high-field and ultra-high-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners and a magnetoencephalography scanner (MEG), which allow scientists to examine brain activity in high spatial and temporal resolution. Research at CoBIC focuses on the cerebral foundations of language and memory, neurological and psychiatric disorders, and the neural mechanisms underlying human abilities, skills acquisition and creativity – the last with a particular focus on music.

Distribution of labor between the two brain hemispheres

This whole process normally takes place in the brain’s left hemisphere, which is the dominant one for language in most people. This explains why people affected by a left-side stroke suffer from speech loss, as the right hemisphere cannot simply take over. But why is that so? In what ways do the left and the right side of the brain differ? Kell says this question has fascinated him since he was a young student. As he has meanwhile learned, one of the reasons is that the left hemisphere is better than the right one at analyzing fast, short signals. “This is, of course, important for language because it’s a signal that varies very quickly over time. In almost everyone, the right hand, which is controlled by the left hemisphere, is better at performing rapid, dynamic movements than the left one.”

Is that really the case? What about a right-handed violinist? She just moves her right hand back and forth a little, while her left hand flits over the strings! “I also thought that at first,” smiles Kell, “but it might not be the whole truth. A friend of mine who plays the violin explained to me that the fine intonation, the dynamics, the musical expression, depends on how you move the bow. Typically, the right hand leads the left one.” The fingers of the left hand, by contrast, provide the context for the delicate work performed by the right one.

In his research on speech production, Kell is mainly interested in finding out what happens when speech no longer functions properly, that is, when people stutter. It is, however, by no means his intention to see stuttering as an illness, since he can understand perfectly well when people who stutter say: “The illness is not inside me. The illness is society’s view of this different way of speaking.” On the other hand, he believes that doctors should at least offer treatment for those stutterers who find it debilitating and seek help.

Electrodes in the brain

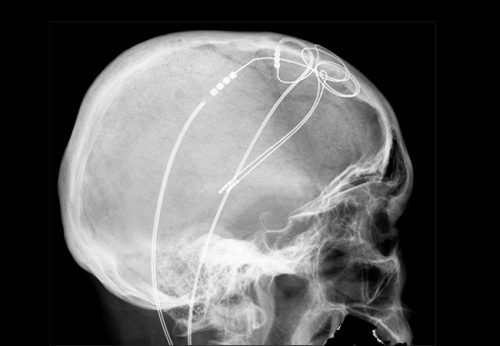

Photo: Hellerhoff, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

Kell’s research drew the attention of a young man with a severe stutter, who announced that he wanted very much to pursue a career after university that would involve a lot of talking. He said he had tried every conceivable type of therapy but failed to achieve a satisfactory result. He knew that Kell and his collaborators working with Professor Katrin Neumann at the University of Münster were conducting research on stuttering throughout Europe and needed them to treat him. He wanted a brain pacemaker.

The team refused, in fact for many years, because deep brain stimulation had so far never been implemented for the purpose of reducing stuttering. Rather, it is a therapeutic method that can be applied, for example, to treat the tremors associated with Parkinson’s disease, where in many cases permanently implanted electrodes that emit mild electrical currents can significantly reduce tremors, albeit with the risk of unwanted side effects.

Apart from psychological factors that contribute to stuttering, there are genes whose mutation increases the risk. Studies with twins also point to a genetic predisposition. Kell and his team have observed changes in people who stutter in studies based on functional magnetic resonance imaging, which visualizes the areas of the brain active during speech: “People who stutter typically have different connections in the left hemisphere of the brain between the motor cortex, which is responsible for speech, and the auditory cortex, which is key to analyzing what was said.” These two areas of the brain evidently do not interact as much in stutterers as they do in people who speak fluently. That is why the former activate the right hemisphere more when they speak, which is, however, not as good as the left one at analyzing short, rapid speech signals. The result is that the right hemisphere is unable to compensate for the faulty wiring in the left one.

Brain pacemaker helped against stuttering

The young man was tenacious, and Kell and the Münster team eventually developed such a convincing hypothesis, based on scientific literature and their own work, that both the ethics committee and neurosurgeons agreed to implant an electrode for deep brain stimulation in his head.

The result? Kell is delighted: “His stuttering decreased by between 40 and 60 percent. That was a much greater effect than I had dared to hope for. A few months after we started with deep brain stimulation, he stuttered far less. When we reduced the treatment, he started stuttering more again.” This was where the therapeutic effect differed from that in Parkinson’s patients, where the tremors disappear immediately after the brain pacemaker is switched on. “In stuttering, the stimulation effect seems to rely more on a slow modulation of the brain circuits.” This might have another, highly exciting cause, explains Kell: “When we switch off the stimulation, the patient’s stuttering is not as severe as before the operation.” Kell thinks the patient themself is responsible for part of this effect. “Because the stimulation has allowed him to experience the sensation of stuttering less, he has found own ways to stutter less than before, even without stimulation.” Kell is convinced: “I think that’s an essential part of how medicine works. I believe that our therapies, apart from a few impressive exceptions, often bring about only a minor improvement, which the patient notices. The patient does the rest. The improvement they experience motivates them and points to ways their body can help itself.”

Now on the agenda are studies to investigate whether this success was an isolated case or whether deep brain stimulation is indeed a treatment option for severe stuttering. In addition, the researchers want to find out whether stuttering can also be reduced without brain surgery. This might be possible by stimulating the brain from the outside in people who do not stutter as severely or who do not want to undergo surgery. And what about the young man? He is meanwhile happily working in his dream profession.

About

Christian Kell, born in 1977, is director of the Cooperative Brain Imaging Center (CoBIC) and a consultant neurologist. He studied medicine at Goethe University Frankfurt, where he earned his doctoral degree in 2005. Research stays and clinical rotations took him to University College London and Lennox Hill Hospital in New York, among other places. As a postdoctoral researcher, he worked for two years at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. He has led the Cognitive Neuroscience group at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2012, which was funded for five years by the Emmy Noether Program, and earned his postdoctoral degree (Habilitation) in 2015.

c.kell@em.uni-frankfurt.de

The author

Markus Bernards, born in 1968, studied biology and earned his doctoral degree at the University of Cologne. He is a science journalist and editor of Forschung Frankfurt.

bernards@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding