Twenty thousand leagues…

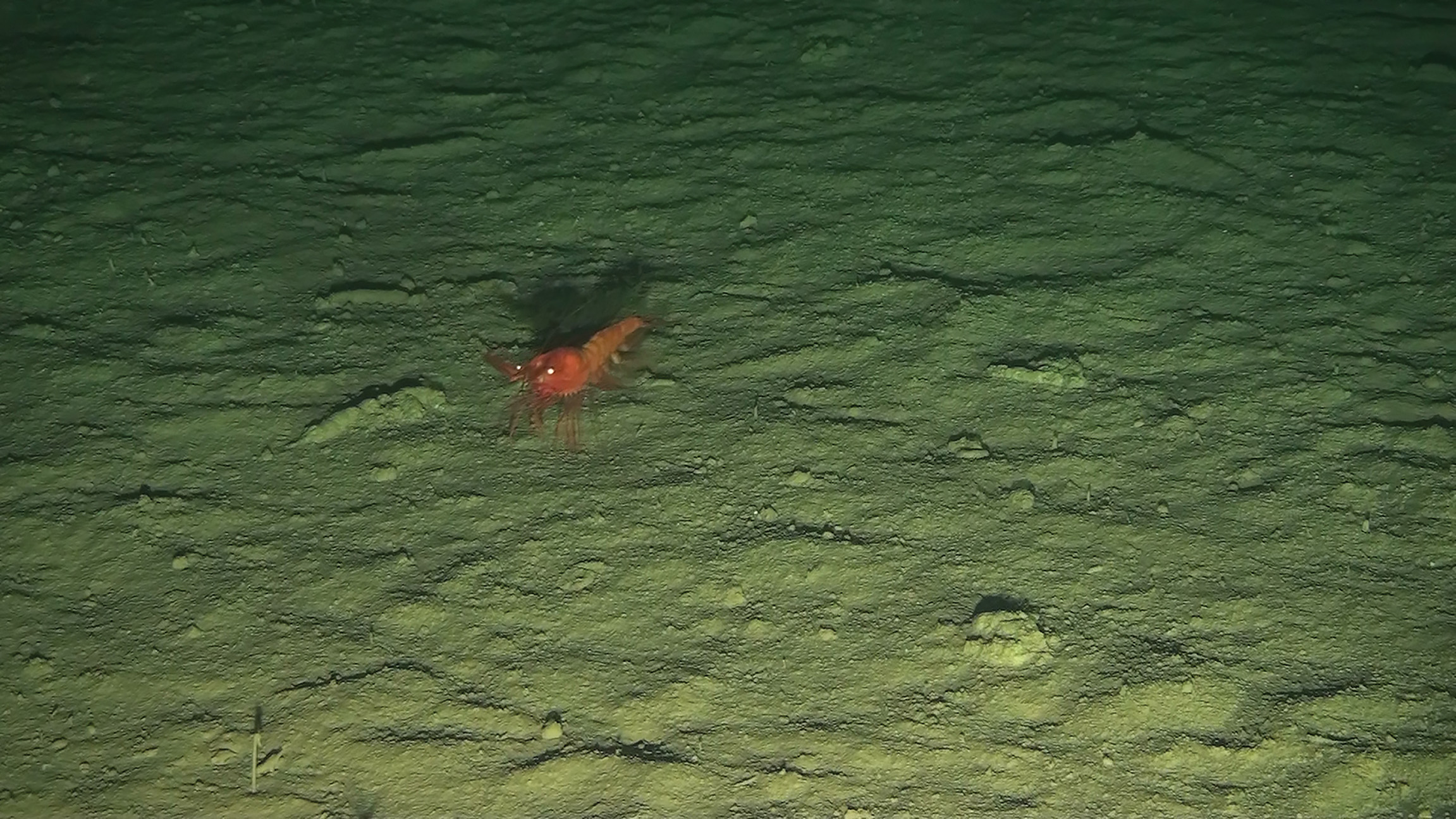

5,378 meters under the sea: deep-sea shrimp in the northwest Pacific.

Photo: Nils Brenke

The deep sea makes up over two thirds of Earth’s surface, and it is probably home to more than half of all species on the planet. And yet so far little is known about this vast habitat. Zoologist Angelika Brandt is studying the animal kingdom of the dark depths, which is mostly alien to us – and in the process has discovered how severely it is threatened by climate change and other global impacts of human activity.

There are more or less no blank spots left on the map, and humankind with its thirst for knowledge is advancing further and further, even in space. Yet right before our eyes lies a vast ecosystem that we know less about than the far side of the Moon – the deep sea. The reason is simple: the deep sea is so vast and deep that the only way to explore it is from a ship and with special equipment.

According to most definitions, the deep sea begins at a depth of 200 meters. Here, eternal darkness and constant temperatures of around just 2 °C prevail. There are other reasons why life in the deep sea is no picnic. With increasing depth, the water pressure rises dramatically – by about 1 bar every ten meters — and food is extremely scarce. Because plants cannot grow in the dark, nutrients mainly enter from the surface of the water, but there is very little sedimentation, as zoology professor and Senckenberg researcher Angelika Brandt explains: “At a depth of 4,000 meters, it takes on average about 1,000 years until a millimeter of sediment forms.” A dead fish or even a whale that sinks to the seafloor and decomposes there is a rare stroke of luck for deep-sea organisms as a source of food. Bacteria that do not need light to synthesize biomass are also important as energy suppliers.

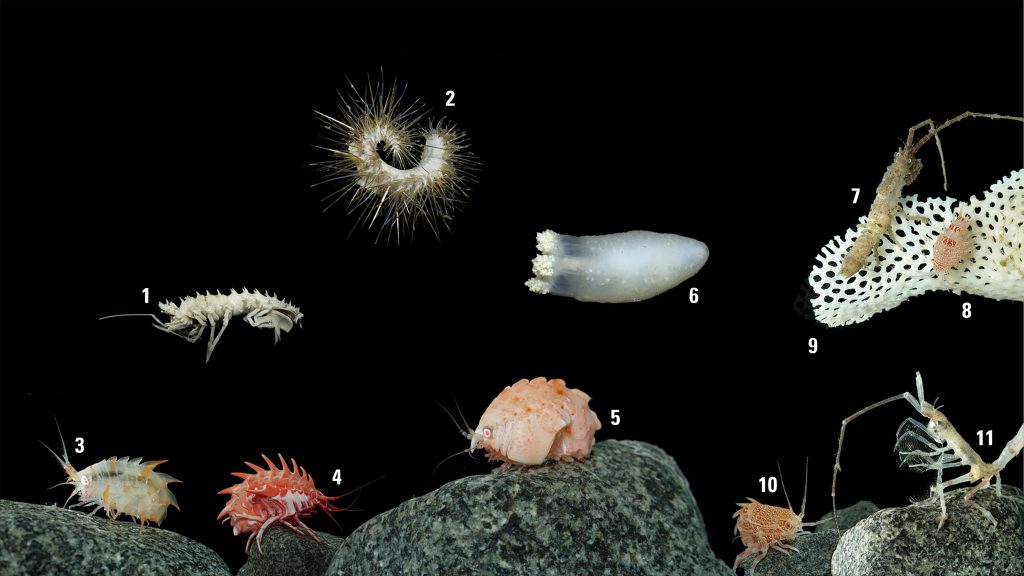

Deep-sea inhabitants: collage of animals (in different magnification) collected on research expeditions with the ship “Polarstern” in the Antarctic. New species are discovered on almost every dive.

1 Deep-sea isopod (Vanhoeffenura sp.)

2 Bristle worm (Eunoe spica)

3 Amphipod (Epimeria similis)

4 Amphipod “Red Knight” (Epimeria rubrieques)

5 Amphipod (Epimeria inermis)

6 White sea cucumber (Psolus sp.)

7 Antarctic isopod (Antarcturus sp.)

8 Amphipod (Anchiphimedia cf. dorsalis)

9 Bryozoan colony (Reteporella hippocrepis)

10 Amphipod (Anchiphimedia cf. dorsalis)

11 Isopod (Dolichiscus cf. meridionalis)

Photo: Torben Riehl, Senckenberg

Key factor in climate developments

For a long time, people were convinced that no life was possible in the cold darkness of the deep sea. In the mid-19th century, the Briton Edward Forbes, one of the pioneers of deep-sea research, set the limit at a depth of 500 meters – and was quite wrong, as results of the Challenger, Valdivia and other expeditions documented. Moreover, “In the 1960s, with their submersible Trieste, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh found life even in the deep-sea trenches at a depth down to 11,000 meters,” says Brandt. The zoologist specializes in the study of macrofauna in the deep sea and the polar regions – that is, animals between half a millimeter and ten millimeters in size, such as isopods, amphipods, snails, mussels and annelids. She gives public lectures about her work on a regular basis, telling her audience how important the deep sea is for biodiversity and for humankind’s well-being and how it interacts with climate change. For example, the deep sea is responsible for 80 percent of the global heat balance and 50 percent of global oxygen production. It also functions as a buffer for the greenhouse gas CO2 from the atmosphere and plays an important role in our climate balance as well as in the water, carbon and nitrogen cycles.

Most importantly, the deep sea is home to an estimated 50 to 80 percent of all species found on Earth. “The deep sea is a vast habitat,” says Brandt and illustrates this in numbers: over two thirds of Earth’s surface are covered by water, about 70 percent of which is the deep sea. “Of this, then again, we only know an area as large as two football pitches in comparison to Earth’s entire land mass,” she says, quoting the late deep-sea researcher John Gage from Oban, Scotland. In this vast habitat, an estimated ten million species are still waiting to be discovered. “Our knowledge of deep-sea fauna is extremely patchy,” Brandt regrets to say. “About 99 percent of all online references to the existence of marine life are related to depths down to 200 meters.” But the world’s largest ecosystems are the abyssal plains (from the Greek word abyssos for “bottomless”), which are found at depths of 3,500 to 6,000 meters. The deep-sea trenches, which can be up to 11,000 meters in depth, are the only place deeper. “Only 0.1 percent of what we know has to do with this habitat below 4,000 meters,” says Brandt.

Unknown and yet threatened

All deep-sea biotic communities, including those as yet unexplored, are gravely threatened by climate change and marine pollution. Slowly but surely, global warming is also affecting the oceans; the CO2 introduced from the atmosphere is converted into carbonic acid in the water and leads to ocean acidification, which makes it difficult for organisms such as snails, mussels and corals to form their calcareous shells. Added to this is environmental pollution from waste: together with colleagues, Brandt recently analyzed the microplastic count in the deep sea – with alarming results. Even at a depth of 9,600 meters, microplastics could still be found. “We don’t know the fauna there yet, but humans have already left their footprint.”

What’s more, precious mineral resources, such as manganese nodules, methane hydrate, crude oil and gas as fossil energy sources or rare earths for computer and solar cell production, make the deep sea attractive for the mining sector. “But the deep sea is not only the world’s largest and oldest ecosystem but also the one that reacts most sensitively when it is disrupted,” says Brandt and mentions studies which show that the biotic communities there only recover very slowly after the extraction of raw materials. “We are currently observing a huge loss of biodiversity in the deep sea. Against this background, it is our task to discover, describe and protect the species living there.”

Research as a logistical challenge

In terms of logistics, however, deep-sea research is extremely complex as well as expensive because retrieving samples from the seafloor can only be done with sophisticated technical equipment. “One day on the ‘Sonne’ research vessel, for example, costs roughly €50,000,” says Brandt to demonstrate the scale. “At depths of 8,000 to 9,000 meters, collecting samples can take up to twelve hours. This means that a single sample costs €25,000.”

Depending on the research question, the scientists use different apparatuses for sampling. The epibenthic sledge, for example, drags two nets across the seabed and gathers small invertebrates such as isopods and amphipods that live on the seafloor or swim directly above it. Small animals such as nematodes, copepods, ostracods, kinorhynchs, tardigrades and gastrotrichs mostly live in the sediment, from which the multi-corer, a sediment drill with an array of polycarbonate tubes, can punch out samples. The box corer punches out larger pieces of sediment and in the process also exposes crabs, mussels and bristle worms, among other organisms. For larger animals – that is, sponges, starfish, sea cucumbers, snails, sea urchins, serpent stars and fish – researchers use the Agassiz trawl, a metal sledge with a trawl net with a mesh size of ten millimeters that drags across the seabed collecting samples.

Because the organisms have adjusted to the conditions in the deep sea, the researchers endeavor to keep these conditions constant during sampling. To this end, the cold deep water is permanently cooled. There are freezers on board to freeze the precious samples at -20 °C or at -80 °C, in the latter case after prior fixation in ethanol with a temperature of -20 °C. At the end of the expedition, the samples are dispatched to the laboratories back home in freezer boxes with a temperature of -21 °C.

Among other equipment, the German research vessel “Sonne” has heavy cranes for lowering the deep-sea robots, which weigh several tons, into the water.

Photo: Senckenberg

From stocktaking to species description

Once the precious samples are on board, the researchers first undertake a thorough stocktaking. To do this, they look at each individual creature under a magnifying glass (binoculars) or microscope and photograph it to document its natural coloration. Genetic analysis enables them to establish relationships and how species are distributed geographically. “Of the species found on an expedition like this, 90 percent are often unknown,” says Brandt with delight. “In 2015, we knew of about 52 species of marine isopods in the Sea of Okhotsk. During our expedition ‘Sea of Okhotsk Biodiversity Studies’ with the research vessel ‘Akademik M. A. Lavrentyev’, we discovered over 1,000 new species just while sorting on board.” Interestingly, the recently completed research expedition AleutBio (Aleutian Biodiversity Studies) with the “Sonne” research vessel (SO293) also brought almost 1,000 species to the surface, some of which are also found in the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench 3,000 kilometers away. The conclusion is that the crustaceans, which are only a few millimeters in size, are common in the deep-sea trenches. “Our samples show only a tiny detail of the deep-sea fauna each time,” she says. “When we find species that earlier expeditions found in the same place or even very far away, it’s unbelievably exciting.”

Species that are particularly interesting from the perspective of evolution or biogeography are described in detail in the laboratory in Frankfurt. To do this, the researchers use modern imaging techniques such as light, scanning electron and confocal laser microscopy. New species are also labelled with a unique genetic barcode derived from the sequence of base pairs of a marker gene – or analyzed in terms of their genome. The specimen of the first description of a new species is deposited as a type specimen in the scientific collection, where future generations can also access it. This is because only the type specimen itself can deliver unambiguous information about the species.

Brandt is convinced that scientific collections will become even more important in the future because international agreements, such as the Nagoya Protocol, aim to achieve an equitable sharing of the benefits generated by the use of genetic resources. One of the consequences, however, is that they are making it increasingly difficult to obtain collection permits. “What’s more, we need to work in a way that is less and less invasive in order to protect biodiversity – in natural history collections, too. That is why we also need to do more research on species that are already deposited in scientific collections.”

At the present time, Brandt’s research is greatly compromised by the war in Ukraine because in the past many expeditions, especially to the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific or to the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench, were undertaken in cooperation with Russian researchers. “Collaboration with our Russian colleagues was incredibly good. Since the war began, this is no longer possible due to national and international regulations,” Brandt regrets. Yet time is pressing. “We are already running the risk that species in the deep sea, the great unknown, will become extinct before we have even discovered them.”

About

Angelika Brandt, born in 1961, has been in charge of the Marine Zoology Department at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt since April 2017 and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. In parallel, she is Professor of Special Zoology at Goethe University Frankfurt. Prior to that, she was a professor at the University of Hamburg for 22 years and director of the university’s Zoological Museum from September 2004 to October 2009 as well as its deputy director for about 10 years. She is conducting research into the biodiversity of macrofauna in the deep sea and the polar regions; her specialization is the group of marine isopods. For her research work, she has participated in 30 marine expeditions so far, several of them in a leading function.

angelika.brandt@senckenberg.de

The author

Dr. Larissa Tetsch studied biology and earned her doctoral degree in microbiology. She then worked in basic research and later in medical training. She has worked since 2015 as a freelance science and medical journalist and is also managing editor of the scientific journal “Biologie in unserer Zeit”.