How precision medicine can help detect risks and treat heart attacks

In 1977, a professor at University Hospital Frankfurt set a milestone in modern cardiology: Martin Kaltenbach used a balloon catheter to dilate a constricted coronary artery. It was the first intervention of this kind in Germany and the second worldwide. Today, David M. Leistner, Director of Cardiology, combines catheter procedures with innovative imaging technology. His goal is individual cardiovascular therapies tailored to specific pathologies.

As one of our vital organs, the heart is a top performer: This hollow muscle about the size of a fist pumps five to six liters of blood through our body every minute – via a system of blood vessels with an overall length of around 100,000 kilometers. From the aorta, which is about three centimeters in diameter, the arteries branch out further and further to the capillaries, whose diameter is only five thousandths of a millimeter. For the 60 to 80 heartbeats per minute, the heart muscle itself also requires a blood supply sufficiently rich in oxygen and nutrients. That is why a dense network of ever-finer coronary vessels zigzags through it, which branch out from the left and right coronary arteries.

If the coronary arteries narrow as a result of progressive atherosclerosis (in lay terms “hardening of the arteries”), there is a risk of an infarction, or heart attack, where the blood supply to the heart muscle is severely disrupted, muscle tissue dies and sudden cardiac arrest can occur. What is understood by atherosclerosis is deposits in the blood vessels, called plaques, on which blood clots (thrombi) can form. These thrombi can detach, causing an acute blockage of the coronary arteries and triggering a heart attack.

The exact mechanisms that lead to the formation of these blood clots and consequently to a heart attack are not yet fully understood. In the past, it was assumed that they develop when the connective tissue surrounding the plaque tears and the material beneath it detaches. However, a study by a research team led by Professor David Leistner, who was then still working at Charité Berlin, revealed that blood clots can also develop on undamaged plaques.

Not all deposits in blood vessels are the same

In the study entitled OPTICO-ACS, the team examined 170 patients who had suffered an acute coronary syndrome (a heart attack). In around a quarter of them, the researchers found that it was not a tear (rupture) but the wearing down (erosion) of the deposits in the blood vessels that triggered the infarction.

The researchers identified that activated immune cells (T lymphocytes) had accumulated at the sites of the plaque erosion – apparently as a result of the altered blood flow conditions in the constricted sections of the blood vessels – where they damaged the vessels’ inner lining.

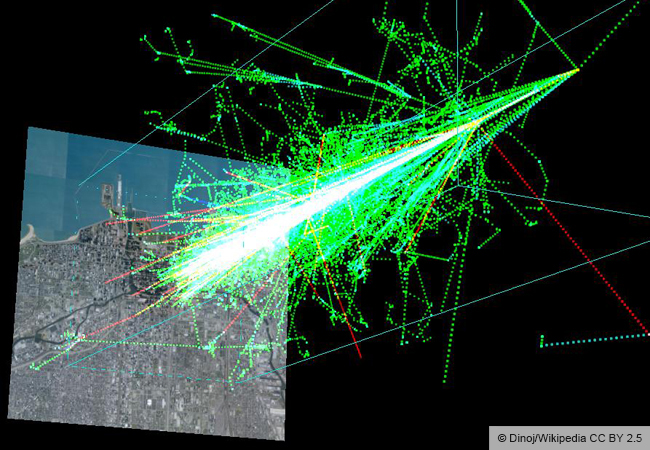

With the help of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a special imaging technique, the research group was able to analyze in detail the plaques that had triggered the patients’ heart attacks and reliably distinguish between rupture and erosion as the cause. A suction catheter was then used to remove the blood clot at the site that had triggered the infarction, and blood samples were taken to examine immune cells and inflammatory markers.

Imaging for precision therapy

OCT imaging is one of the components of Leistner’s treatment concept, which, together with his team, he is continuing to develop in Frankfurt. Treatment with a cardiac catheter inserted through a vein in the arm or leg (percutaneous coronary intervention, PCI) is accompanied by high-resolution intracoronary imaging, such as OCT as mentioned above, both in the planning phase and when monitoring whether the PCI was successful. “We call this ‘precision PCI’,” explains Leistner. “The aim of precision medicine is to offer personalized therapies that are specifically tailored to patients’ individual needs. In oncology and gynecology, tailor-made therapies based on genetic and hormonal characteristics have already been available for some time. In cardiovascular medicine, however, we have neglected this approach for too long,” Leistner is convinced.

In another study, Leistner and his colleagues examined the consequences of rupture or erosion as triggers of acute coronary syndrome for the further course of the disease. This study also used OCT imaging. Acute coronary syndrome is a working diagnosis for chest pain that includes several types of myocardial infarction and their precursors.

The study cohort comprised 398 patients with acute coronary syndrome, who joined the study one at a time. In 62 percent of the patients, plaque rupture was detected (ruptured fibrous cap, RFC patients), while 25 percent displayed intact fibrous caps (IFC patients). Disease progression differed significantly in the two groups: Those with plaque rupture had a higher risk of a pronounced inflammatory reaction and of serious cardiovascular complications later on.

This means, especially in the case of RFC patients, that anti-inflammatory treatment could prevent their condition from worsening. “The data from this study, which we presented at the ESC Congress 2023, organized by the European Society of Cardiology, could lead to the ‘precision PCI’ concept becoming the interventional standard,” hopes Leistner.

How plaques form

It is important to understand that not all plaques are the same, he explains: “There are different types of plaques, from calcified to active, ‘vulnerable’ plaques. Vulnerable plaques have thin caps that increase the risk of rupture and contain a lot of lipids and very little calcium. Such plaques are particularly dangerous and often lead to serious complications.”

One method for detecting plaques at an early stage is computed tomography (CT). The newest generation of CT scanners can spot even dangerous, unstable plaques. “In my opinion, the future lies in offering people between 40 and 65 years of age a CT scan to determine whether they have vulnerable plaques,” says Leistner. “If they do, preventive measures need to be taken, such as lowering their cholesterol or treating inflammation to improve plaque stability. To study these mechanisms in greater depth and understand them better, we are using both clinical and translational models.”

For example, the researchers analyze plaque samples extracted with a catheter. “We look at the molecular basis of these plaques as well as the genetic profile and which metabolic pathways are active. We also examine inflammatory processes and the production of proteins associated with plaque formation.” In parallel, the researchers use mouse models, he says, to study plaque formation in more detail. “This enables us to gain a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms. We are especially interested in why certain plaques that have not become inflammatory can nevertheless lead to dangerous complications. This will help us develop new approaches for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.”

Poem by Rilke helps with early detection

Professor Leistner believes that digitalization, such as the use of apps and digital platforms, presents new opportunities to monitor patients’ health more effectively and to implement or adjust personalized preventive strategies. One of the research projects on which the team is currently working is the use of voice analysis to detect heart problems. “We use a smartphone app to record a person reading a poem by Rilke and can deduce from their voice whether the heart is pumping properly or fluid is being retained. This type of monitoring could be an efficient way to detect heart problems early on,” concludes Leistner.

About / David Manuel Leistner, born in 1981, was appointed as Professor for Internal Medicine (Cardiology) at Goethe University Frankfurt in 2022 and has been Director of the Department of Cardiology and Angiology since then. After completing his doctoral degree at LMU in Munich, he earned his postdoctoral degree at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and was appointed Professor for Interventional Cardiology there. From 2017 to 2022, he was Managing Senior Physician in the Department of Cardiology at Charité and headed the TAVI program (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (a minimally invasive intervention)) and the cardiac catheterization laboratories. His scientific interests lie in translational research on the pathophysiology of acute coronary syndrome, interventional cardiology with intracoronary imaging and CHIP interventions, digitalized precision cardiology for preventive cardiology and cardiac insufficiency therapy, and geriatric cardiology.

david.leistner@ukffm.de

The author / Die Diplom-Biologin Gabi Fischer von Weikersthal studied biology and learned the ins and outs of science and medical journalism during a two-year traineeship at a medical publishing house and further training at the Akademie der Bayerischen Presse (ABP – Bavarian Academy of Journalism). She reports from national and international congresses/press conferences and is a ghostwriter/editor for medical/scientific texts. She lives in Germersheim and Lagos in the south of Portugal.

fvwpress@mail.de