When sports scientist Karen Zentgraf talks about her approach to research, tangible aspects like training sweat and performance improvement come to mind. But more than that, her accounts evoke thoughts of cyberspace and science fiction. The goal of her studies on individualization is to collect as much data as possible from an athlete to create a systemic and multidisciplinary representation, also known as an “avatar”. The head of the Movement and Training Science department explains: “Instead of analyzing studies with the highest sample sizes, we gather as much data as possible from individual athletes to obtain a data-driven representation of the person, which then guides decisions on interventions.”

Mechanisms of Movement Control

As part of her movement science research, Zentgraf is especially interested in how the brain controls movements and how people manage to create effects in their environment through movement. “I focus on both consciously controlled actions and automated movements,” she adds. While her work primarily centers on situations involving competitive athletes – whether it’s a hand, foot, or racket sending a ball or puck into the goal, or a tennis ball being hit into the opponent’s court where it’s unreachable – her findings are equally applicable to everyday scenarios, such as when an average person moves their hand to a light switch and applies pressure with their fingers to illuminate a room. These insights shed light on fundamental mechanisms of movement control.

Training science also benefits from Zentgraf’s research, including athletes seeking to organize their training efficiently and sustainably to optimize their physical fitness. However, her primary focus remains on competitive and elite sports. “Especially for women and girls,” Zentgraf emphasizes, adding that, “Similar to medicine, sports science has predominantly focused on male subjects for decades.” Zentgraf wants to help close the resulting “gender-data gap”. Her research also considers aspects of physiology, such as the female cycle, along with nutrition, anatomy, and biomechanics.

Zentgraf also comes across gender differences exploring psychosocial aspects: “In German elite sports, we’ve encountered a surprisingly high number of female athletes who feel burned out and experience what’s known as a gratification crisis,” she explains. “This means they perceive an imbalance between effort and reward, which our research has identified as a burnout risk factor.” Another contributing factor is that female athletes often feel externally controlled. Gymnasts on the German national team, for instance, were required until recently to perform their routines, including splits and leaps, in prescribed competition attire consisting of short, tight leotards. They are now allowed to wear long pants.

A Successful Athlete

When Zentgraf studies phenomena related to the psychology of competitive athletes, her own experience in the world of competitive sports proves invaluable: She was a German youth champion in heptathlon and played in the volleyball Bundesliga. But it’s not just her sports career that has benefited her work in sports science – it’s also her first field of study. Zentgraf initially began studying medicine and decided after completing her preliminary medical exam to simultaneously enroll in sports science. “Even in high school and during a sports scholarship in the U.S , I was fascinated by biological processes in the human body, so it was quite clear to me that I would study medicine. At the same time, I came from competitive sports, so it made sense to pursue sports science as well,” she recalls.

While studying sports science, she already saw her medical studies and athletic career as valuable for shaping relevant research questions. Even now, her approach to sports science topics is strongly influenced by her background. “How can I better support elite athletes in enhancing their performance while staying physically and mentally healthy? That’s where we offer evidence-based approaches,” Zentgraf explains.

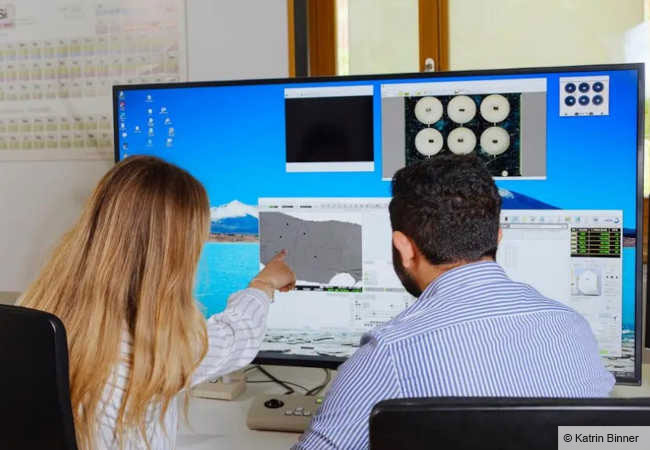

Discovering these is part of the collaborative project “in:prove – Performance Reserve Individualization,” in which her department and the computer science faculty at Goethe University have joined forces with Justus Liebig University Giessen and the German Sport University Cologne. The project, which has been running since 2021, was recently extended for another three years until 2028. “We take into account that all elite athletes we study are individuals – they bring different motor and cognitive abilities, each has their own psychosocial background, their blood micronutrients, their genetic makeup, and their gut microbiome are uniquely configured,” says Zentgraf. The aim is for each individual to enhance their athletic performance as much as possible in a healthy and sustainable way. “It is important to keep in mind that everyone has different performance reserves. Some benefit from specific training adjustments, others from improving cognitive flexibility or working memory, optimizing their diet, or changing their training group.” With the help of “avatars”, Karen Zentgraf and her team develop tailored interventions for everyone.

Stefanie Hense