On the humming tasks of the translator

to the “second body” of a poem that feeds a translation: “the body that drifts back and forth over the text, as it were, between the source and the target language, a construct of sound, rhythm, similarities, silhouettes shaped from letters, chance and latent multilingualism.”

No one knows better than Buster Keaton the delights, horrors and opportunities that translating poetry presents: This surprising hypothesis was the starting point for poet and translator Uljana Wolf in the lecture she gave to inaugurate the new Monika Schoeller Lectureship for Literary Translation at Goethe University Frankfurt in the 2024/25 winter semester.

The title of my lecture indirectly echoes a prose poem from Ilse Aichinger’s collection “Schlechte Wörter” (“Bad Words”) published in 1976. Due to the contiguous, partly multilingual prose poems in this volume, I assumed for a long time that its title – “Surrender” – was an English verb, meaning “to give up”. It was only later that I realized – perhaps because of the first sentence – “Ich höre, dass mit Tricks und Kniffen gearbeitet wird, Membranen, durchlässiges Zeug, hell, hell.” (“I hear that tricks and ruses are in use, membranes, permeable stuff, light, light.”) – that the title might speak another language, too. Or rather, that it speaks a German which simultaneously translates itself into another language. And in that case, we could read the title as “(ein) Surrender” (“someone who whirrs”), an unusual noun made from the German verb “surren”. And so, I want to dedicate this lecture to Aichinger’s other-language, but also to all other-languages of the future.

When I was racking my brains yet again about how I, as a translator, could save my own language from the predicament of our times and say something substantial for this lecture, I decided to distract myself with a silent movie. This move was not inspired by some ingenious conceptual translation – the association of “writer’s block” with “non-talkie” occurs here more by chance – but instead by my predilection for diversions and the catastrophic offerings of slapstick.

Fotos: Szenen aus The Balloonatic (1923), Regie: Buster Keaton und Edward F. Cline. Verwendung im Rahmen des Zitatrechts (§ 51 UrhG) zur Erläuterung der filmischen Metaphorik im Beitrag von Uljana Wolf. Quelle: https://archive.org/details/the-balloonatic-1923

And this is why I would like to speak to you today about a previously unknown translator: Buster Keaton. I would like to claim that no one has captured the delights, horrors and opportunities of the kind of poetry translation we urgently need for our times better than Keaton in his silent movie “The Balloonatic” (1923). Already the title – a portmanteau of balloon and lunatic – is a word translators can easily identify with, reminding them, as it were, of their foolish, often hardly adequately compensated infatuation with language, their hours spent chewing over an expression which for others is just hot air.

As the film begins, we see a man in a room with several doors, a kind of chamber of horrors he’s desperately trying to escape from. Yet behind each door lurks a new menace: skeletons, weird creatures, swirling mist. Helplessly the man finds himself in the middle of the room again, when suddenly a trapdoor opens, and he is catapulted down a slide into the street. And now we see that he is at a fairground, and the labyrinth of doors is called “House of Trouble”. Its entrance looms so dark and large and is so big that its throat could easily swallow the whole world, or perhaps it has already swallowed it, but we don’t know it yet (Buster presumably knows!).

Strolling around in search of other attractions, the man finally climbs into a hot-air balloon, which takes off without him knowing, and with a bottomless gondola – something translators are very well acquainted with. Yet this gondola turns out to have all kinds of useful equipment in bags attached to the sides, including a canoe. Soon after a crash landing on the bank of a river, the countryside, too, becomes a “House of Trouble” for Keaton’s fool. First, he assembles the canoe incorrectly so that it sinks, then he catches himself with the fishing rod that leaves him dangling in the air. The fish, on the other hand, don’t want to do what he presumably wants them to do, and as for the bears – well, let’s not go there –, and finally his encounter with a strong, nature-savvy camper (Phyllis Haver) leads first to more disaster and finally to a – rare for Keaton – happy ending.

Buster Keaton – the unknown translator

Fotos: Szenen aus The Balloonatic (1923), Regie: Buster Keaton und Edward F. Cline. Verwendung im Rahmen des Zitatrechts (§ 51 UrhG) zur Erläuterung der filmischen Metaphorik im Beitrag von Uljana Wolf. Quelle: https://archive.org/details/the-balloonatic-1923

The happy ending reveals that the Balloonatic has been a translator all along. That while he was struggling with the things life presented him with, he was working on a method to grasp them differently, and to piece them together anew. For in the end, the canoe floats after all. And since it also turns out to be equipped with a canopy, it simultaneously manages to serve as a romantic bower for the enamored campers. And when the small concoction floats towards a steep waterfall but, instead of falling over the edge with the two lovers onboard, simply keeps floating onwards through the air, it turns out that the balloon from the beginning of the movie is also here again, this time tied to the canoe. Et voilà – a portmanteau boat gliding through the clouds. In it, the two lovers resort to doing the only right thing one can do in a canoe held aloft by strings on a balloon: They canoodle. The movie doesn’t “say” this, but at this point something in me has begun to pick up Keaton-the-translator’s thread. The etymology of the verb “canoodle” is murky. There are various folk etymologies, one of which, evidently the decisive one for this translator, assumes that it originated in the Victorian era, when a two-seater canoe was the only way to evade the chaperone’s watchful gaze. In the last scene of the movie, the two outer parts of the canoe break away. It is now completely transformed and fulfills its new purpose as a loveseat in the air. As if “can” and “dle” have fallen off the ends of the word and only the two “O” remain, like the heads of two people in love.

Non-understanding as creative, hallucinatory rewriting

“The first principle of all Keaton’s comic personae,” the poet Charles Simic wrote, “is endless curiosity. Reality is a complicated machine running in mysterious ways whose working he seeks to understand.” In my interpretation, this curiosity goes even further. It seems to me that the comical attempts through which Buster Keaton’s characters want to understand the machine – that is, the world – are in fact also attempts to build another machine. In reality, he is busy translating what Novalis called “the strange interplay of the relations of things”; his non-understanding is a creative, hallucinatory, literal, childlike rewriting of the world. It shows how one can fail at the established order of the world and fall against it, act against it by rearranging its parts – with more obscure rules, a sense of nonsense, physical poetry, acrobatic melancholy, a whirring play on words (in a silent movie!) and perfectly timed punchlines that Keaton never bungles. In my opinion, this is no different than translating a poem.

Keeping the melancholic acrobat in mind, I would like to talk today about how one of the most important skills required for translating poetry is not to get everything right, but to get everything right in the wrong way. About how feeding the translation from the second body of the poem, with precise timing and a furious playfulness wrested from despair, with slapstick and wordplay, is what matters. By “second body” (a term which I borrow from Daisy Hildyard) I do not mean the version in the target language, but rather the body that drifts back and forth over the text, as it were, between the source and the target language, a construct of sound, rhythm, similarities, silhouettes shaped from letters, chance and latent multilingualism. A construct that is constantly changing, that connects, planned or unplanned, with all things and bodies surrounding it. What matters is less the poem that can be disassembled word for word according to all the rules of linguistic reason, measured in terms of its ambiguity of meaning, and reassembled in the target language. What matters more is the poem whirring around in the air, with a silly canopy and a balloon clumsily affixed to it, calling

out “OO”.

The poem’s “second body”

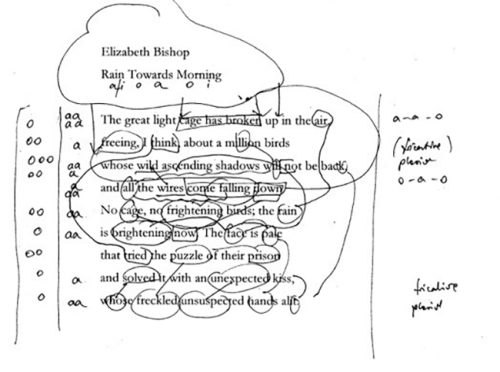

I want to read a poem by Elizabeth Bishop to explain what I mean. It is one of her shorter ones and part of the collection “A Cold Spring” (1955). The poem evokes a rain shower at dawn, it’s a poem about how everything is relational, connected – sky, rain, flocks of birds, observer, bodies, love, desire, loss.

Monika Schoeller Lectureship for Literary Translation

In the final analysis, all poetry is translation” – this claim by Novalis marked the launch

in the 2024/25 winter semester of the new Monika Schoeller Lectureship at Goethe University Frankfurt. Created in memory of the publisher Monika Schoeller, the aim of this lectureship is to reflect on and promote the theory and practice of literary translation once a year in lectures, workshops and readings, especially in view of the increasing advance

of machine translation. The lectureship was sponsored by the S. Fischer Foundation and the Freies Deutsches Hochstift, one of the oldest cultural institutes in Germany and a non-profit research institution, in cooperation with the Institute of German Literature and its Didactics and the Institute of General and Comparative Literary Studies at Goethe University Frankfurt. The inaugurating lectureship was curated by Frederike Middelhoff and Caroline Sauter; supervising the event with Eva Schestag in the winter semester are Frederike Middelhoff and Judith Kasper. All three are professors of literary studies at Goethe University Frankfurt.

Uljana Wolf, born in Berlin in 1979, one of the most prominent contemporary German poets and translators, is the first lecturer. Her most recent publications are the poetry collection “muttertask” (2023) and a collection of essays and talks entitled “Etymologischer Gossip” (2021).

Uljana Wolf has translated numerous poets from English and Eastern European languages into German, including works by Christian Hawkey, Eugene Ostashevsky, Valzhyna Mort, Don Mee Choi, and recently – from Korean, together with Sool Park, the poetry collection “Autobiography of Death” by Kim Hyesoon, awarded with the International translation prize of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt 2025.

Uljana Wolf has received numerous scholarships and awards, including the Peter Huchel Prize (2006), the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize (2016), the Berlin Art Prize (2019), the Prize of the City of Münster for International Poetry (2019 and 2021), the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in the non-fiction/essay category (2022) and the Ernst Meister Prize of the City of Hagen.

Rain Towards Morning

The great light cage has broken up in the air,

freeing, I think, about a million birds

whose wild ascending shadows will not be back,

and all the wires come falling down.

No cage, no frightening birds; the rain

is brightening now. The face is pale

that tried the puzzle of their prison

and solved it with an unexpected kiss,

whose freckled unsuspected hands alit.

What happens in the poem? The rain from the title trickles down into the first line, prepares us with a setting, a downpour of questions. Is this more of a great cage of light (“Lichtkäfig”) or also a bright cage (“lichter Käfig”), or a little more of a light-weight cage (“leichter Käfig”)? Do we see a cloudburst, a downpour? And if so, are “a million birds”, introduced by the hesitant “I think”, a metaphor for raindrops? But how, then, can their “wild ascending shadows” depart and disappear in the next line? Perhaps the raindrops, conversely, are a metaphor for birds? A flock startled by a cloudburst; the shadows of the birds, themselves as ephemeral as cloud formations, spreading their wings as dawn breaks? And what, then, falls down in the fourth line, which with precise timing induces a break: “and all the wires come falling down”? Here, the subject of the sentence changes; it is no longer the cage from the first three lines, but “all the wires” – the wire bars of the imagined cage, like streaks of rain, perhaps. Like something big that broke apart and about which we cannot say exactly, even after reading the second part, whether this breaking is met with sadness or relief, or both. This state of limbo alone would, however, hardly be worth mentioning, and we would not get ecstatic about the interpretation outlined here, if the linguistic structure of the poem itself were not like a cage that both exists and breaks open, with both birds and bars, a shower of trickling vowels and wiry threads of consonants.

Busy structuring the world

The tonal counterparts and patterns of letters are closely meshed and distributed in the poem – almost like a grid. There is the string of four gerunds: “freeing-falling-frightening-brightening”. There is a second string of four words with double “l”: “million-will-all-falling”. There are the varying strings of “a” and “o” in “cage has broken” and “come falling down”, each introduced by a “c”, open on one side like a cupped hand, or an open link in a chain. There are the twin echoes of the softly humming “wild-wire” and the creaking “unexpected-unsuspected”. There is the abundance of the vowels “a” and “o”, which, if you were to string them together, would visibly thin out towards the bottom of the poem, like easing rain. Wherever I look, listen or touch, a new thread of sounds or sight unfurls and joins up with another thread; little by little, the strings starts to hum (“surren”), the poem takes off, becoming a humming thing (“ein Surrender”), and I climb around in its ropes like a balloonatic.

This reading, obsessed with sound and texture, happily drifts towards nonsense and at the same time shows us a path towards translation. Because just like Buster Keaton, we are constantly busy rebuilding the world. But it is not meaning that we pursue. We hover over (“sur”) the “rendering” of meaning, we have surrendered and delivered ourselves to the humming (German: “surrenden”) being-there of the text. And via this approach through the material aspects of the poem, in other words: the walls of the gondola rather than the semantics of its bottomless floor, I think we will be able to better grasp the sensual nature of the linguistic machine that this poem represents, perceiving how a word in a poem is most likely than not motivated not by its meaning, its content, but a relational echo, a proximity, a similarity or a variation. This precise, humming, hallucinatory reading enables us to break open the cage of our own language and – “I think” – to unleash a million possible sounds in its inherent multilingualism, to start playing, to let the translation – a new language – emerge from the second body, from the childlike mimetic mood of sounds and poetic speech.

This text is an excerpt of the lecture given by the author as part of the newly created Monika Schoeller Lectureship for Literary Translation at Goethe University Frankfurt. The full text will be published by S. Fischer Verlage. English translation by Sharon Oranski and the author.

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Sprache, wir verstehen uns!