Watching evolution happen – with the help of seed banks

by Andreas Lorenz-Meyer

Photo: Elke Zippel, Dahlem Seed Bank

Evolutionary ecologist Niek Scheepens investigates how plants adapt to climate change. He obtains seeds from seed banks that were stored there decades ago and compares the traits of the plants that germinate from them.

A number of plant species are acutely threatened with extinction, through the destruction of their habitat, climate change or environmental pollution. To preserve biodiversity, seed banks have been established all over the world since the beginning of the 20th century, initially only for crops such as cereals, pulses or fruit trees. Later, ones for wild plants were added so that species will not be lost entirely if the natural populations indeed die out in the future. The stored seeds could then be used to reintroduce a species in nature. Alternatively, stored seeds could be sown in small and endangered populations as a preventive measure – in the hope of increasing their chances of survival.

To observe the consequences of climate change, plant researcher Niek Scheepens has conducted an experiment with seeds from such seed banks. The research project was called “Back to the Future”, inspired by the Hollywood movie of the same name. Although the scientists themselves did not travel back in time in the experiment, they did bring research objects from the past into the present.

Scheepens and his research team took hundreds of seeds from seed banks – most notably the Meise Botanic Garden in Belgium and the Conservatoire Botanique National Méditerranéen de Porquerolles in Southern France – and planted them in a greenhouse at the University of Tübingen. The seeds from the seed banks were between 21 and 38 years old and came from perennial plants from locations in Central Europe, the French Alps and the southern part of the French Mediterranean. In the experiment, seeds of the same species from the present were planted alongside the seeds from the past. The former were collected in 2018 in the exact same natural locations of the plants. Both ancestors and descendants passed through the individual life cycle phases of germination, growth, flowering and fruiting. “Some had difficulty,” reports Scheepens, who conducted the experiment with Robert Rauschkolb, his doctoral student at the time. Many plants did not flower at all or only in the third year, some seeds did not even sprout. But in the end, at least 13 species yielded usable results: Past and present plants differed measurably in their appearance, which was precisely what the experiment was about.

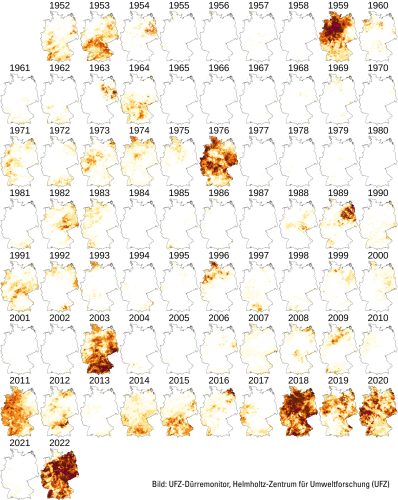

Plants flower earlier

In 5 of the 13 species studied, the plants of today flowered much earlier than the plants of yesterday, including the awl-leaved plantain Plantago subulata, which grows on rocky soils along parts of the Mediterranean coast. Its tiny, sulfur-yellow flowers appeared much earlier in the descendants than in the ancestors. It was a similar story for Clinopodium vulgare, commonly known as wild basil, which thrives on poor, calcareous soils in temperate zones and forms pink to dark pink, lip-shaped flowers. Here, too, the descendants set the pace and were much earlier than their ancestors. Next, the scientists analyzed the climatic development at the original sites for each population. They discovered that the earlier flowering time was consistent with worsening drought in the region. This had turned the plants from the present into early bloomers.

Scheepens explains the mechanism: “It has to do with Darwin’s theory of evolution. Variation in plant traits initially arises by chance, and when trait variation is heritable, those plants whose trait expression is better suited to a new environment can increase in abundance. If the environment gets drier, only the plants that flower earlier will survive. Their seeds then mature before drought makes further plant development impossible. This allows the plants to continue producing offspring.” Annual plants have only one season to adapt, perennials can sometimes afford a bad year. Once the change is genetically anchored, the new trait value is passed on to the next generation. The plants’ offspring also flowered earlier – support for evolutionary adaptation through selection.

The experimental approach that Scheepens adopts for his research is called resurrection ecology. This approach differs from resurrection biology, or de-extinction, which aims to bring back currently extinct species, such as the gastric-brooding frog.

Watching evolution happen

Resurrection ecology examines species that still exist: animals, fungi, bacteria or – as in this case – plants. It shows how quickly populations evolve and how well or poorly they adapt. Time is the dimension that forms the basis for the experimental test: Scientists cultivate organisms that were collected in the past together with organisms collected recently from the same location and examine them for differences in traits. In this way, by comparing past and present, evolution can be measured.

Scheepens’s greenhouse experiment has achieved this goal. “These were rapid evolutionary processes that took less than 40 years,” says the biologist. “We could almost watch evolution happen.” However, there was also a catch: In a greenhouse, it is not possible to demonstrate experimentally whether evolutionary adaptation is behind the changes in a plant’s traits. This is due to the “unnatural conditions”: The plants are regularly fertilized and watered, which does not happen in nature. The light in the greenhouse is also different to that in the natural location. It is therefore impossible to say whether the plant reacted to the environmental changes or whether random processes were involved, for example mutations or other random changes in the genetic makeup of a plant population through the introduction of new gene variants (gene flow) or the random disappearance of gene variants (genetic drift).

Adaptation or coincidence?

To solve this question, from 2021 to 2023 Scheepens conducted another experiment with his doctoral student Pascal Karitter, this time in the field. At four locations in two regions in Belgium, the 23 to 26-year-old ancestors and the descendants of four wild herbs were planted together at their original location: Clinopodium vulgare (wild basil), Leontodon hispidus (a kind of dandelion commonly known as bristly hawkbit), a species of grass called Melica ciliata (hairy melic) and the flax Linum tenuifolium. “In their original habitat, all natural environmental influences, everything they are familiar with, affect these species. Then we see how fit they are, the plants of yesterday and those of today. In this way, we can find out whether the changes came about through selection and if we are actually dealing with evolutionary adaptation.”

The researchers were the first to combine resurrection ecology and plant cultivation at the place of origin in this way. Unfortunately, the two summers of 2022 and 2023 were very hot and dry, which is why the plants of three of the four species under study died before flowering. “If they had flowered, we could have measured whether the descendants produce more seeds than the ancestors. Then all three aspects of fitness would have come together: survival, growth and reproduction. Unfortunately, experimental research in the field is anything but easy.” Nevertheless, there were some revealing results. For the hairy melic, Melica ciliata, for example. The descendants of this delicate species of grass were much fitter than their ancestors in the hotter, drier present: They grew taller and had more leaves. Their mortality rate was also lower.

Scheepens’s conclusion: This greater fitness is the result of evolutionary adaptation through natural selection. There are several factors that substantiate this. “Firstly, the differences between ancestors and descendants are statistically significant. It is unlikely that these were coincidental.” In addition, there is the combination of changes in Melica ciliata: less mortality AND better growth. “This means that we have two plant responses from very different stages in the plant’s life, both of which show a pattern of greater fitness. This lends credibility to our interpretation of evolutionary adaptation.”

It is also important to remember that mortality itself is a strong indicator of selection, as it is a matter of survival for the plant. The dandelion-like Leontodon hispidus was also interesting. The seeds of its descendants had a higher germination rate than those of the ancestors. “However, this result is not easy to interpret in terms of adaptation,” says Scheepens. Allowing only part of the seeds to germinate could also be an advantage for plants. If the next heatwave completely eradicates these seeds, the population still has some in reserve.

What can we expect next in this still relatively young field of research? Scheepens is certain that resurrection ecology will become an integral part of the evolutionary ecologist’s toolbox. He outlines how this approach can lead to useful insights: “If a plant population has adapted well so far, then it will probably continue to be able to do so. If, on the other hand, the population has adapted poorly, it may not survive. We can even make such statements for the whole species – insofar as several spatially separated populations show the same inability for evolutionary adaptation.” It is then clear

that this species relies on migration. For example, it would need to spread to cooler areas because conditions have become too hot at the place of origin. Resurrection ecology results can be used to make better predictions about how global changes – climate change, but also changes in land use or the decline of pollinators – influence the evolution of organisms. “And not just how they could do it, which can be simulated in evolutionary experiments, but how they actually do it.”

However, such comparative studies also need a solid foundation, i.e. seed banks that provide good, reliable material. Scheepens sees considerable room for improvement in Europe as a research location. “Seed banks usually only store seeds from a single population. It is therefore impossible to make statements about the evolution and adaptation of a particular species as a whole. We can only say something about the evolution and adaptation of this one population.” In addition, it is often not known how early or late in the season the seeds were collected. Individual plants in the same location can flower at different times, which resurrection ecology studies must take into account. And seed banks do not always store the seeds in exactly the same way, which could lead to plants developing different trait expressions. That is why Scheepens is proposing a European seed collection project based on “Project Baseline” in the US. In Colorado, millions of seeds, collected at hundreds of locations according to clear specifications, are stored in a vault at – 18° C. The material is intended for future resurrection ecology studies that should shed light on how plants respond to climate change and other environmental problems. According to Scheepens, if we had something like this in Europe, we would in future have the best possible biological material at our disposal.

Environment and genes

Evolutionary ecologist Niek Scheepens is also investigating changes in the genetic code itself as part of the resurrection ecology studies. To this end, he is looking at single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. SNP is the term for variations of individual base pairs in DNA. The vast majority of SNPs have no effect on plant traits, they are only subject to neutral evolutionary processes. Many SNPs can be used to determine FST, a measure that expresses neutral genotypic differences between populations. Analogously, QST, a measure of phenotypic differences between populations, can be calculated on the basis of the traits measured directly on plants. Resurrection ecology studies compare these two values over time. “If the QST value is greater or less than the FST value, we can deduce that natural selection has occurred,” explains Scheepens. A greater QST value means “divergent selection” – traits diverge. A smaller QST value means “stabilizing selection” – traits remain stable despite neutral evolutionary processes. In the case of the greenhouse plants, for example, the values measured in Leontondon hispidus indicated a strong divergent selection. “This supports our hypothesis that the population has repeatedly adapted to the changing climate over the decades.” The data from the field experiment are yet to be analyzed.

About Niek Scheepens

Evolutionary ecologist Niek Scheepens has been a professor at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2020, where he heads the Plant Evolutionary Ecology Working Group at the Institute of Ecology, Evolution and Diversity. Scheepens holds a Bachelor’s degree in philosophy of science and a Master’s degree in biology from the University of Groningen, Netherlands. In 2011, he completed his doctoral degree at the University of Basel and worked there for a year as a postdoctoral researcher. After a two-year research stay at the University of Turku in Finland, he joined the University of Tübingen

in 2014 as an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow, where he led a junior research group from

2017 to 2020.

About the author

Andreas Lorenz-Meyer, born in 1974, lives in the Palatinate and has been working as a freelance journalist for 13 years. His areas of specialization are sustainability, the climate crisis, renewable energies and digitalization. He publishes in daily newspapers, specialist newspapers, university and youth magazines.