How different proteins are produced from the same template

by Larissa Tetsch

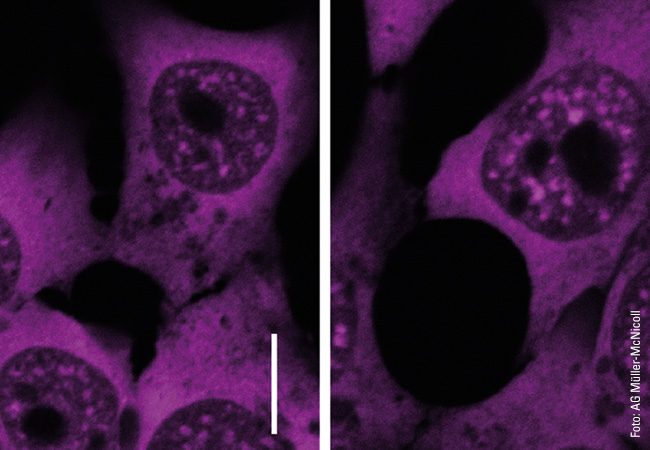

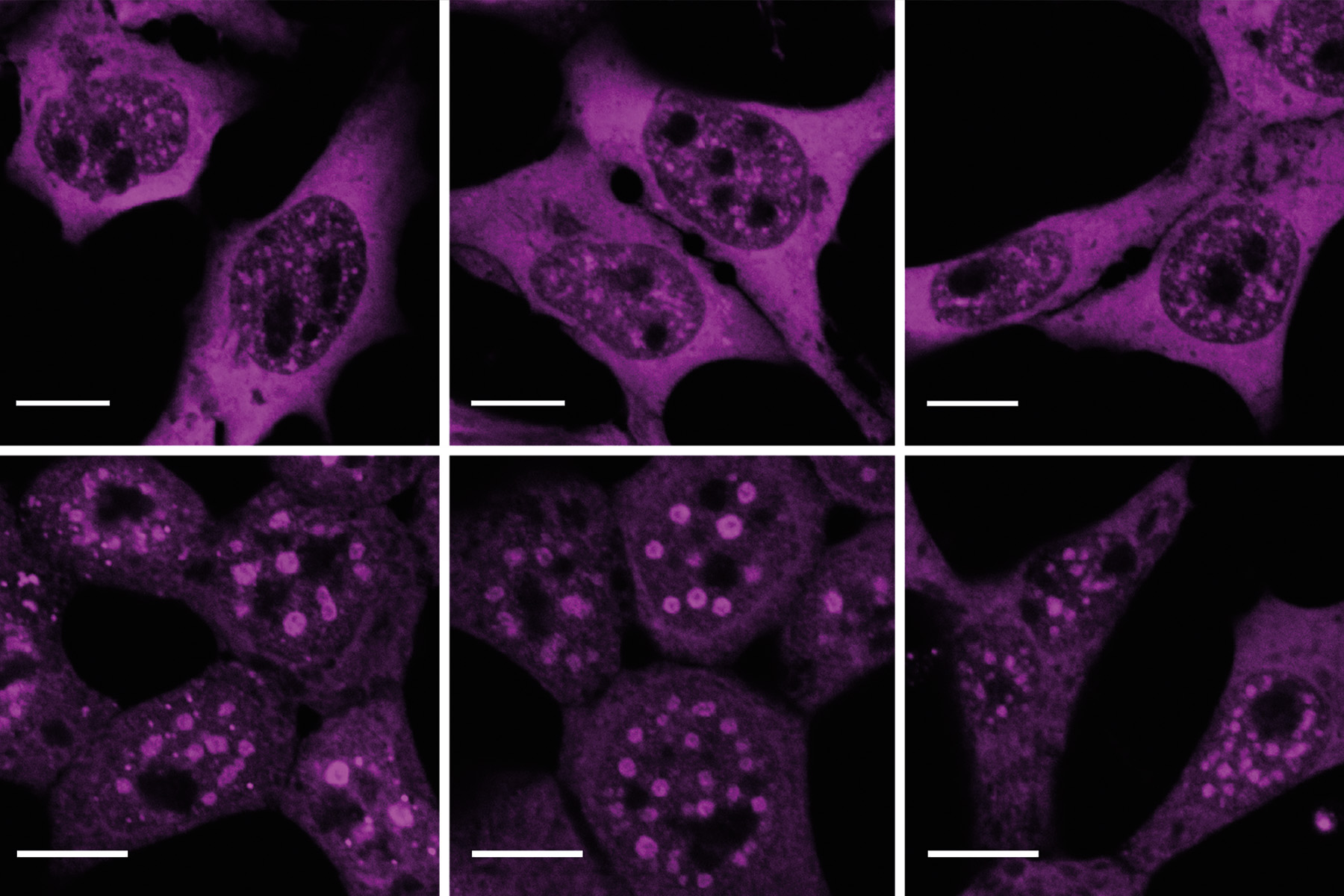

Photo: Müller-McNicoll WG

The human genome contains around 20,000 genes that serve as instructions for building proteins: a surprising contrast to the 100,000 proteins that our cells actually produce. Michaela Müller-McNicoll is investigating how the cell does this.

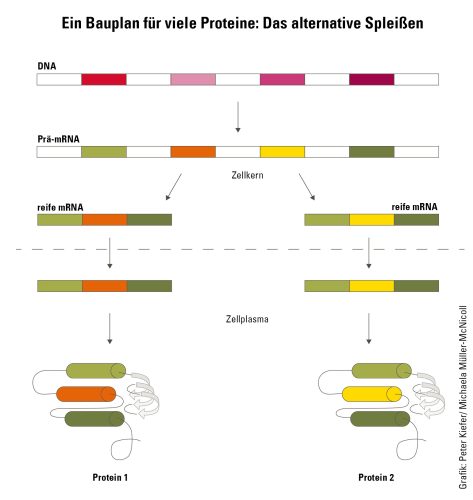

Proteins are the cell’s “workhorses”: They are required for almost all tasks – from metabolism and the assembly of cellular building blocks to energy production and the formation of a wide variety of structures. No wonder, then, that a cell is bustling, as it were, with an enormous variety of proteins, whose building instructions are encoded in the genome in the form of genes. However, in humans and many other living organisms, there are significantly more proteins than genes. To produce this diversity, a process known as alternative splicing comes into play. Alternative splicing makes use of the fact that genes have a modular structure: They contain sequences that make up parts of the protein – the exons – and ones that are no longer contained in the protein – the introns. Exons often code for an area of a protein. This is called a domain and performs a specific function in the protein. During splicing, the exons can be combined in different ways so that different blueprints for protein production are created from the same template. Michaela Müller-McNicoll, who as a professor at the Institute for Molecular Bio Science at Goethe University Frankfurt is conducting research on the regulation of alternative splicing, explains: “During splicing, the cell chooses which areas of a gene a mature RNA should contain. This modulates or completely changes the function of a protein.” For example, two splice variants can differ in whether or not they possess a specific domain for binding to other proteins, or whether they remain inside the cell or are incorporated into the cell envelope.

“The decision as to which exons will later remain in the protein is already made while the gene is being read in the cell nucleus,” says Müller-McNicoll. During transcription, the messenger RNA, also known as mRNA or transcript, is produced. After splicing and further maturation processes, the transcript is transported from the cell nucleus to the cell interior (cytoplasm), where it serves the ribosomes as a blueprint for the production of a protein.

“I am interested in the role that subcellular architecture plays in splicing decisions,” says Müller-McNicoll, describing her field of research. She explains how “subcellular architecture” can be pictured: “You can imagine a cell as a house with different rooms. Like these rooms, a cell has different compartments or organelles, such as the cell nucleus with the genome as the command center, the mitochondria for energy supply and ribosomes for protein production. In addition to static architecture such as biomembranes or pores, through which a regulated exchange of substances can take place, a cell also has dynamic architectural elements that form or degrade under changing circumstances. Like sliding room dividers, proteins that are important for splicing decisions can be spatially separated from the mRNA and released again as required.” Such dynamic architectural elements that perform regulatory functions are at the center of Müller-McNicoll’s research.

Protein group with many tasks

Müller-McNicoll already discovered her “love” for RNA – as she herself says – during her doctoral studies at Laval University in Canada – back then, she was still working on the parasite Leishmania, which causes the tropical disease leishmaniasis. “Leishmania exhibits a particularly fascinating gene regulation,” she says. “Unlike most other organisms, it is not transcription that is regulated, but all the processes that follow – starting with the stability of the transcripts

to splicing and protein production in the ribosomes, that is, translation.” However, during her time as a postdoctoral researcher that followed, Müller-McNicoll wanted to switch to a different model system. “When you work with a model system as exotic as Leishmania, you have to develop all the techniques and molecular tools yourself,” she recalls. Switching to a vertebrate such as a mouse or the human being as a model system, by contrast, opens up many more possibilities because a wealth of established techniques already exists, she says. As a young researcher, she found what she was looking for in Karla Neugebauer’s group at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden. “That is where I started to study alternative splicing in human cells.”

Her work soon focused less on RNA and more on the RNA-binding proteins that control alternative splicing. There are many variants of these serine and arginine-rich (SR) proteins, which are very similar in structure and involved together in many tasks. In addition to alternative splicing, these tasks include the export of the spliced transcripts from the cell nucleus and even translation, which takes place outside the cell nucleus. Here, several SR protein variants usually perform the same task. From a biological perspective, this makes good sense, as Müller-McNicoll explains: “Gene regulation has to be robust, which is why it is good if a protein can step in as soon as another one malfunctions. However, some SR proteins appear to have additional domains for other functions that have not yet been studied in full.”

SR proteins are crucial for survival, which is underlined by the fact that virtually no mutations are known. “A loss of function in the proteins probably leads in most cases to the death of the organism,” says Müller-McNicoll. If, by contrast, SR proteins are produced in excess due to dysregulation, cancer often develops because “all alternative splicing decisions are altered.”

Rapid adaptation to stress

However, SR proteins not only influence which protein variants are formed from a gene. They can also prevent certain proteins from being formed at all, for example by ensuring that certain transcripts are degraded before they can be translated into proteins. Or they prevent the transcripts from leaving the cell nucleus. “We know that the SR proteins can shuttle back and forth between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm,” says Müller-McNicoll. “As this shuttling can be switched on and off, it can function as a regulatory signal.” The researchers in Frankfurt were able to show that shuttling changes during cell development. In differentiated cells, i.e. ones that have already developed into a specific type of cell, such as a lung cell or a skin cell, the SR proteins are no longer shuttled. “The transcripts that they normally transport out of the cell nucleus then remain in the cell nucleus, which allows quick decisions on differentiation,” explains Müller-McNicoll.

While she initially concentrated on individual SR proteins, Müller-McNicoll now wants to find answers to overarching questions: “For me, it is important to keep sight of the bigger picture. There are many demarcated areas in the cell nucleus where different proteins are waiting to go into action. They work together there as a group and form functional units. This is the focus of our research. SR proteins are found, for example, in nuclear speckles. They are only released when required, that is, when the decision has been made to splice a certain exon. This enables a rapid response to a change in environmental conditions.”

Müller-McNicoll’s team is investigating this rapid response mechanism using the example of oxygen deficiency, which represents a significant stress factor for cells. “We can see great momentum in the assembly and degradation of nuclear speckles and the release of SR proteins, which is important for the adaptation process,” says team leader Müller-McNicoll, summing up. She plans to use these results to collaborate with researchers investigating diseases in which oxygen deficiency plays an important role, such as cardiovascular diseases. “We have a broad portfolio of methods that we can use to shed light on underlying mechanisms, and scientific teams working in cardiovascular diseases can try them out in test systems relevant to such diseases, for example in the form of organ-like cell cultures or mice with corresponding clinical pictures. In this way, both sides can benefit from each other’s results.”

Blueprint for many proteins: Alternative splicing

Active participation in research cluster

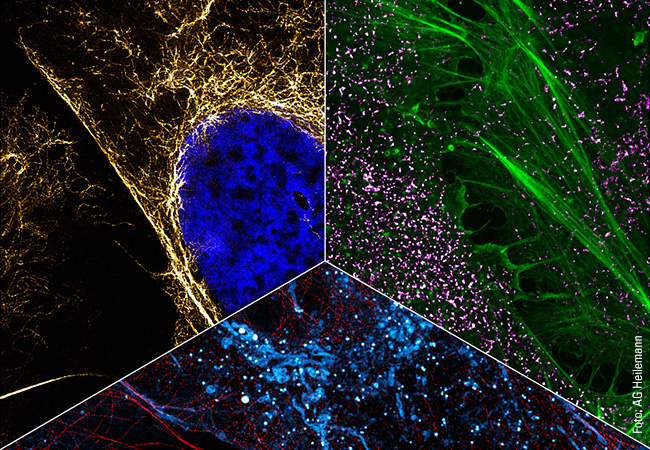

Although conducting research on SR proteins is not easy, Müller-McNicoll is convinced that the work is worthwhile. Because the nuclear speckles cannot be isolated from the cell nucleus, researchers are obliged to find other ways of studying them. Among other things, she is counting on super-resolution microscopy. For this purpose, she is collaborating with Mike Heilemann’s group at the Institute of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry (see p. 68). “To gain a better mechanistic understanding of cellular compartments, we are also working closely with scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics in Frankfurt,” says Müller-McNicoll. This interdisciplinary collaboration is also at the forefront of the SCALE (Subcellular Architecture of Life) research cluster, which is currently submitting an application for funding to the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments and which Müller-McNicoll represents as one of the spokespersons. “Within SCALE, we are working on overarching questions that cannot be tackled by one team alone,” she is convinced. “Among other things, I would like to see structural research pay more attention to protein variants produced through alternative splicing. I am also contributing my expertise to the study of protein areas that do not have an ordered structure. Such areas are difficult to explore, but immensely important especially for interactions with other biomolecules and therefore for the formation of subcellular structures.” That Michaela Müller-McNicoll is delighted at the thought of being able to answer such complex questions in the SCALE cluster in the future is clear to see. Fortunately, there are more than enough such questions in her field of research to last a lifetime!

About Michaela Müller-McNicoll

Michaela Müller-McNicoll is a professor at Goethe University Frankfurt, where she heads the “RNA Regulation in Higher Eukaryotes” research group at the Institute for Molecular Bio Science. She studied at Humboldt-Universität in Berlin and earned her doctoral degree at Laval University in Quebec, Canada. She was then a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden before joining Goethe University Frankfurt – first as a junior professor and then as a full professor from 2020 onwards. Müller-McNicoll is one of the three spokespersons for SCALE, an interdisciplinary research cluster at Goethe University Frankfurt, and one of the elected directors of the RNA Society for the term 2022 to 2024. .

The author

Dr. Larissa Tetsch studied biology and earned her doctoral degree in microbiology. She then worked in basic research and later in medical training. She has been working as a freelance science and medical journalist since 2015 and is also the managing editor of the science magazine “Biologie in unserer Zeit”..