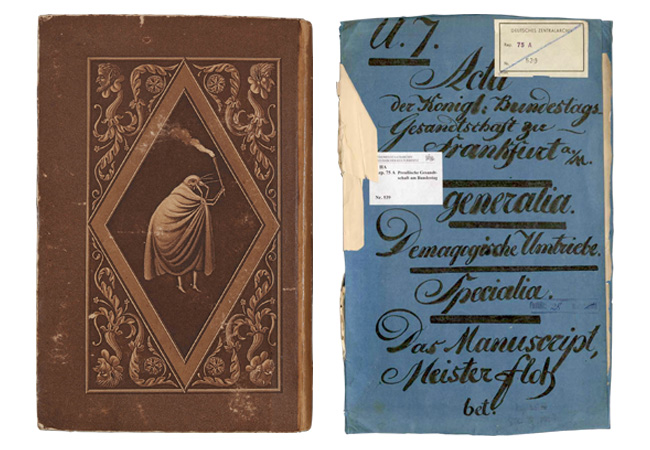

With “Ultraworld”, Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg lead their audience into a simulated world

All photos: Julian Röder

Our everyday life is becoming more and more digital. As a medium that can play with notions of reality and actuality, theater, too, is virtualizing reality, but in an artistic way. Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg confront the audience with a technologized manifestation of theater that at first seems mysterious. In doing so, they repeatedly lead it to the threshold between a physical and a virtual perception of the world.

At the beginning of the play “Ultraworld”, a bodiless voice resounds. It is the voice C/C/A, an acronym for Computer/Child/Animal. It is speaking to the avatar Frank, who is sitting cross-legged on a cube in the middle of the stage, with virtual reality glasses on his nose:

»If the virtual reality apparatus, as you call it, was wired to all of your senses and controlled them completely, would you be able to tell the difference between the virtual world and the real world?«

The question of the difference between the virtual world and the supposedly real world superimposes itself over the entire production – and runs like a thread through almost all the works that Kennedy has created in recent years. What is it like living in a world which constantly spawns new technologies? How does a world develop? Are we living in reality? Is it not rather the case that our notions of reality are meanwhile so permeated by digital experiences that the boundaries between the virtual and the real world are blurred? Is there any self-determined human action at all?

In her works of recent years, Kennedy at times set off in her search for answers along paths that were spiritual, philosophical, hypnotic, psychedelic or inspired by literature. In 2013, she caused a sensation in the German-speaking world with her stage adaptation of Marieluise Fleißer’s “Fegefeuer in Ingolstadt”. Already back then, it was especially the lip synchronization technique that met with a tremendous response. In this technique, other people’s voices are recorded on tape, which the actors mimic on stage like a kind of playback. Since then, Kennedy’s theatrical works, which she brings to the stage with her experienced team, consisting of sound designer Richard Jansen, video artists Rodrik Biersteker and Markus Selg, and other creative personalities, have aroused admiration, but also vehement rejection. For some, going to see a Kennedy production is a must – for others, this kind of theater means little or nothing, they sleep through the performance or else leave.

Construction of hyperreal worlds

Kennedy and Selg’s collaboration began with their project “Medea.Matrix” at the Ruhrtriennale 2017 theater and music festival. In 2019, they created their first joint work for the Volksbühne (“People’s Theater”) in Berlin: the walk-in installation “Coming Society”. Kennedy had already previously staged “Women in Trouble” there in 2017. “Coming Society” was about the construction of a hyperreal world. The audience was able to visit individual stations on the revolving stage and watch the actors perform repetitive, almost ritualistic actions. It resembled an experimental set-up about the acceptance of human finitude and was illuminated by Selg’s large-scale video projections and symbols on the walls. A whispering issued from the speakers: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born.” In January 2020, they staged “Ultraworld” at the Volksbühne theater in Berlin, a play about the emergence of a simulated world. Further collaborations followed with the walk-in VR installation “I AM (VR)” in 2021, “Jessica” in 2022 and the opulent three-and-a-half-hour musical theater production “Einstein on the Beach” in 2022.

Especially with “Ultraworld”, Kennedy and her team have created a theatrical model of modern-day humankind as it wanders, alienated and unfamiliar, between reality and virtuality, between technology and analogy. In so doing, Kennedy and Selg get close to existential questions of life: What is reality? How did the world in which we live come to be, and what does bodily life feel like? What constitutes being human? How can we accept the finiteness of human life?

Kennedy and Selg use a broad repertoire of creative tools to lead their audience into the simulated world of “Ultraworld”. A fluid-like projection, dark on the inside, then bluish to violet and magenta towards the outside, moves across the surface of the movable screen, which hangs at the front of the stage of the Volksbühne instead of the iron portal. The video screen closes off the stage space behind it, which is not yet visible at the beginning of the play. The frame, also projected onto the screen, is reminiscent of computer game aesthetics and ancient Egyptian motifs. Changing projections dance across both the frame and the stage space and seem to be infinitely changeable. The stage becomes a window into another world.

Deep, reverberating, spherical sounds and a gentle hissing can be heard. Then speed is simulated. The images flicker. A maelstrom into the depths of space or a journey into a pre-Platonic cave? A female voice resounds out of the loudspeakers: “In the beginning, there was only darkness everywhere. That was the dormant Universe. Not a breath. Not a sound. The world was motionless and silent. And heaven was empty.” The script contains elements about the creation of the world handed down from the Mayan culture of Central America, from Hindu stories and from Genesis, the first book of Moses. Then another narrative about the creation: “In the beginning, there was only the great self, reflected in the form of a human being. Thinking about themself, they found nothing but themself. And their first words were (at this point the movable screen opens): This am I.”

A simulated world

The play “Ultraworld” does not have a plot in the classical sense. It addresses questions about the creation of the world – the real one and the virtual one – by simulating a world on stage. “Ultraworld” is also the name of the computer game into which the audience is drawn through the scenes acted on stage and the characters. The actors live through and suffer the virtual reality of the game, but also question its rules:

»Ultraworld is a game in which a blond male/female avatar explores a maze filled with different patterns and landscapes. There are choices to be made but regardless of the choices made, across the next 2 hours, the avatar invariably ages, and ultimately dies.«

This is how a voice offstage introduces the game. Earlier, the audience witnessed how the avatar Frank, played by the performer Frank Willens, underwent two so-called “tests”. Frank is the “blond male avatar” of the game and the play’s main character at the same time. He tries to understand the “Ultraworld” rules. In the process, he is also searching for himself, his own identity in this world that seems alien to him. Although he is able to make a few decisions, there seems nevertheless to be no escape for him from the game.

The simulated world on stage is suffering from a severe water shortage, as we learn from the radio positioned on the stage. By undergoing various tests, the avatar tries to save his family, his wife and child called April 1 and 2 and also spoken by recorded voices from offstage, from dying of thirst. But at the end of each test, they die. Dying on stage is not a new motif in Kennedy’s work. “The bodies there die over and over again for us in the play. And we watch and practice,” she wrote back in 2014. In the “Ultraworld” tests, the simulated world is enacted like a model. For the audience, this is also a test that proves to be a great challenge due to the tiring, repetitive loops of the scenes, the booming bass sounds in between and the flickering, garishly colored projections.

Theater as an exceptional place for alienated speech

Kennedy describes theater as a space where an exceptional state prevails, “an exceptional space in which we can test suffering together: via these bodies that stand before us and speak or else do not.” This statement is strongly reminiscent of Aristotle’s Poetics: the theater as a force that can effectuate catharsis, a purging of the spectator’s emotions.

Yet where does the alienated speech lead? Through the technique of recorded voices, which are mimed on stage via lip synchronization, the performance appears to be controlled by others. The pre-produced audio recordings – except for the voices of Frank Willens and Kate Strong, who plays the character M in “Ultraworld” – do not come from the performers themselves. M impersonates the programmer of the game. She has understood the rules. Her name is also an enigmatic reference to the “am” of “I am”.

As in some of the director’s previous works, many of the “Ultraworld” texts were recorded by extras, amateurs or members of the production team without any prior rehearsals, then spliced and reassembled by Richard Jansen, the sound designer. In the process, any slips of the tongue inevitably present during the informal reading of the texts were deliberately amplified in post-production. Accentuated in this way by technical means, these slips of the tongue are very effective. On the one hand, they highlight the artificiality of speaking on stage, and at the same time they point out the unnaturalness of supposedly perfect speech. Talking, crying, breathing, laughing or the child’s singing, a “lalalalala” that resounds at the beginning and at the end – they are all taped. This seems alien and also a little creepy. The alienated speech leads to a radical dissolution of the unity of body and voice within the human representation on stage. The characters do not appear as homogeneous figures, nor as holistic identities, but rather as plastic structures, as body shells.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Theater producer Susanne Kennedy uses new forms of expression and stage techniques to communicate a theatre experience that has a hypnotic effect on the audience. It sucks it in, as it were, and often remains mysterious.

- Her play “Ultraworld” is the theatrical model of a simulated world in which characters speak alienated texts, undergo tests, perform sequences of movements and choreographies, and search permanently for themselves in the process.

- With a perfect composition of stage elements such as the mechanics of the stage background, sampled sound collages of noises, sounds, voices, video and light projections, Kennedy produces a confusing, alienated and at the same time compelling effect.

- All characters are divided into voice, body and role and thus radically de-personified and alienated. The production presents reality as a simulation and shows how humans are entangled in the technologized world that surrounds them.

Watching and listening to the play on stage is strenuous because not all references can be deciphered. In addition, music and video recordings provoke deliberate confusion in time and space. The recorded voices of other people, the psychedelic and symbolically charged stage design and the fact that some performers appear in different roles further contribute to this. Suzan Boogaerdt, for example, plays Cassandra, and Cassandra in turn takes on the role of April 1, and later Gabi. In addition, Boogaerdt is a professional mime artist and can thus narrate stories solely with facial expressions and body movements and without verbal language.

Radical alienation

The complicated, the convoluted, the confusing – all this is intentional because the mysterious itself is part of Kennedy and her team’s artistic strategy. It is not only the unanswered questions that remain enigmatic: Where do the characters come from? What roles are there? Who embodies whom, how? Who is speaking? Is there a plot, or are there merely loose sequences of scenes? Where is the connection? Where is the scene taking place?

The spectators’ unsolved impressions and thus their perception of the events on stage also remain enigmatic. The alienation of speech and movement, the convoluted plot, the simulated world of the computer game, the apparent hopelessness of the game’s progression, but also the droning bass sounds, the flickering video projections and the hypnotic visualizations on the stage create a feeling of unease among the audience.

This feeling of unease, which must inevitably befall the spectators, is bundled in the figure of the avatar Frank. It seems that he does not quite fit into this simulated world, even though he himself originates from it. He is caught in the loop of “Ultraworld”, and he is alone. No escape, perpetual return, perpetual repetition. At the end of the second test, he calls out to M “I want out!”, and M replies “The only way out is in.” All tests end with the screen descending and a pink-and-black flickering projection of an image of a cultic natural deity and booming music. The portal closes, ending the scene, ending the test.

The production presents a simulated idea of the world in which humankind enters the stage as an invented being, as an avatar connected and entangled with their technological environment. Interrupting this alienation of humankind from itself and its environment seems impossible. In this way, the work indeed leads into a simulated world and displays it as a model. It remains open whether our perception of the simulated world then really appears alien due to the technical alienation or rather indicates the extent to which the moments of the present are also determined by feelings of alienation and unease. What is clear, however, is that there is no such thing in the world as an existence that is detached from its environment: just as the avatar Frank is ensnared in the game, so too are the spectators at the fluid transition between a mental and a virtual experience of the world, not only in but especially outside the theater.

Towards the end of the game, Frank can accept the finiteness of life or else capitulates in view of the tiring and merciless recurrence of the same, unchanging situation. Will he find himself as a result? That is rather unlikely. Then the rear portal of the Volksbühne auditorium opens. Rising fog, flickering lights on the floor and resounding chanting set the atmosphere. A colorful crystal, an obelisk hung upside down and in a garish, neon-colored mosaic pattern, descends and illuminates the rearward part of the circular stage as a light and color installation. The obelisk speaks:

»What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning. And the end is where we start from.«

The game can begin again.

The author

Eva Döhne, born in 1989, is a doctoral researcher in theater studies at Goethe University Frankfurt. She studied theater, film and media studies and philosophy in Berlin, Leipzig and Frankfurt. Her doctoral thesis is entitled “The (Un)representability of Women in Theory and Theater”. She is also dealing with historical and contemporary performance art, intersectionality, gender studies and questions of representation.