How to better understand and create networks

Illustration: Yuichiro Chino/Getty Images

Synthetic networks are booming. Today, computer simulations of networks are used to study things as diverse as neural connections in the brain, internet traffic or power grids. A team of researchers led by Ulrich Meyer from the Institute of Computer Science at Goethe University Frankfurt has now taken an important step forward by improving standard methods for creating such networks

Our whole life is embedded in a wide variety of networks. This includes not only our social relationships, which today are partly influenced by algorithms via social media. The everyday products we buy also require a complex web of supply chains and logistics before they end up on the shelf. The electrical power that comes out of the socket depends on a complex grid that is being continuously expanded and reconfigured as renewable energies are used more and more.

The more complex networks are, the more difficult it is to predict how information will be disseminated or how fluctuations or disruptions will have an impact on the flow of goods or electricity. However, because the basic structure of all networks is the same – they are composed of elements (nodes) that are linked to each other via connections (edges) – all networks can be represented and analyzed in an abstract way. To describe them, theoretical computer science and mathematics have created a powerful tool called graph theory. An important focus of current research is synthetic networks, which are generated in the computer and are not true reproductions of a real network. In this form of representation, the elements, e.g. things, actors or events, are simulated in the form of nodes that are connected to each other via edges. This resembles the way nerve cells are connected via synapses. On the one hand, this makes brain research an important source of inspiration for theoretical computer science – and on the other hand synthetic networks are an efficient tool for studying real nervous systems. But such networks can also be used to simulate infrastructures, such as road, electricity and water networks.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Anyone wanting to better understand electricity, financial, viral or supply networks, for example, or to make them more secure must test how information is disseminated and the impact on them of disruptions and fluctuations.

- If technical or data protection reasons complicate the analysis of real networks, they can be simulated using synthetic networks.

- Researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt are developing synthetic networks that do not require supercomputers but instead can run on off-the-shelf PCs.

Tests on artificial networks

“There are many applications that require synthetic networks,” says Ulrich Meyer, Professor of Algorithm Engineering at Goethe University Frankfurt and a fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies (FIAS). In some applications, data protection plays a role, which is why, for example, people often use only simulated data to study contacts between users on social media. Or researchers want to play through different scenarios that do not yet exist in order, for example, to introduce new functions in social media and examine possible links between people beforehand. Sometimes, it is also extremely difficult to obtain exact data, such as in the case of neural connections in the nervous system. In physics, too, large amounts of synthetically generated data are needed to train algorithms for many different applications. In some network analyses, the real-world datasets are so vast that it would take a long time to feed them into a supercomputer.

But such an “electronic brain” can generate a comparable synthetic network itself in a short time. This is because supercomputers not only have thousands of processors, which enable extremely fast computing operations, but also the enormous memory capacity that is needed to access and process the many gigabytes or terabytes of data that larger networks can produce. On the downside, computing time on supercomputers is expensive and limited in terms of availability. “That’s why we’ve been working with our research team for years to optimize the processes for generating synthetic networks,” says Meyer. The goal is to make working with larger synthetic networks feasible on ordinary computers. So far, however, the 8 to 16 gigabytes of RAM available on most computers are not up to the task, as computer scientist Meyer explains: “This is where the difficulty lies because the computer has to transfer data from RAM to the hard disk, which significantly increases loading times for unstructured access patterns. This slows down the computer significantly – by several orders of magnitude – and can quickly make working with such networks impossible.”

PC instead of supercomputer

Another member of the team is Manuel Penschuck, whose doctoral thesis dealt with the generation of synthetic networks. He is now working as a postdoctoral researcher in the Frankfurt group. As he points out, the scalability of such processes is crucial. “If it were possible to create large networks on ordinary computers in a reasonable amount of time, then this could make many applications possible that today we cannot even anticipate,” he says. This has often been the case in the past: new technical possibilities lead to new applications. When the first personal computers came onto the market, no one could have imagined that private individuals would ever need more than a few megabytes of storage space. But today, video games, image processing and video editing require many gigabytes of data.

The fact that so many unstructured access operations occur when creating synthetic networks is due to the networks’ architecture: “In many network models, if you add a new node to a network, it can be linked to random other nodes from the existing network,” explains Penschuck. “If the old node is not in the main memory but located on the hard disk, it must be read from there first.” The Frankfurt researchers have therefore developed special systems for mitigating slow hard disk or SSD access.

Performance savings through smart structures

“Our process is based on smart data structures,” says Meyer. In smart structures, the nodes are pre-sorted and then stored in structured blocks in the memory. Sufficiently complex networks can also be divided into smaller sub-networks. Adding new nodes and connections can then be parallelized – that is, spread over several processor cores in the computer. To process a variety of tasks more quickly, today’s computers have several processor cores on the central chip. This also speeds up the generation of synthetic networks accordingly.

“With the help of all these tricks, we can prevent computing speed from being brought to its knees as soon as the network no longer fits into the computer’s main memory,” says Penschuck. “Indeed, we pay for that because our method – due to the way that the data are structured – is somewhat slower in smaller networks than the equivalent standard process for generating synthetic networks. But while the standard methods on large networks are roughly a thousand times slower once the memory is filled up with the network data, the network generators we have developed lose hardly any speed.”

Networks for the next epidemic

In the future, the researchers want to make synthetic networks more accessible. So far, handling them still requires a high level of skills in computer science and a certain amount of practical training. The aim is for such networks to be easier to use in the future, particularly in areas that are important to society, such as simulating infection chains in epidemiology or analyzing contacts in social networks in the context of social informatics. “That’s why we want to develop a kind of toolbox for synthetic networks that you can use without much previous knowledge and that nonetheless provides all the important tools,” explains Meyer.

This toolbox will include not only the new network generator but also many other processes developed by the global research community in recent years. This software package could then be used in many fields – in epidemiology and socioinformatics, but also in physics and the analysis of power grids. “We are curious ourselves to see how these networks will be used,” says Meyer. The possibility of working with large networks on off-the-shelf PCs without having to apply (and pay) for computing time on supercomputers and outsourcing sensitive data is likely to be interesting for researchers from a wide variety of disciplines.

About

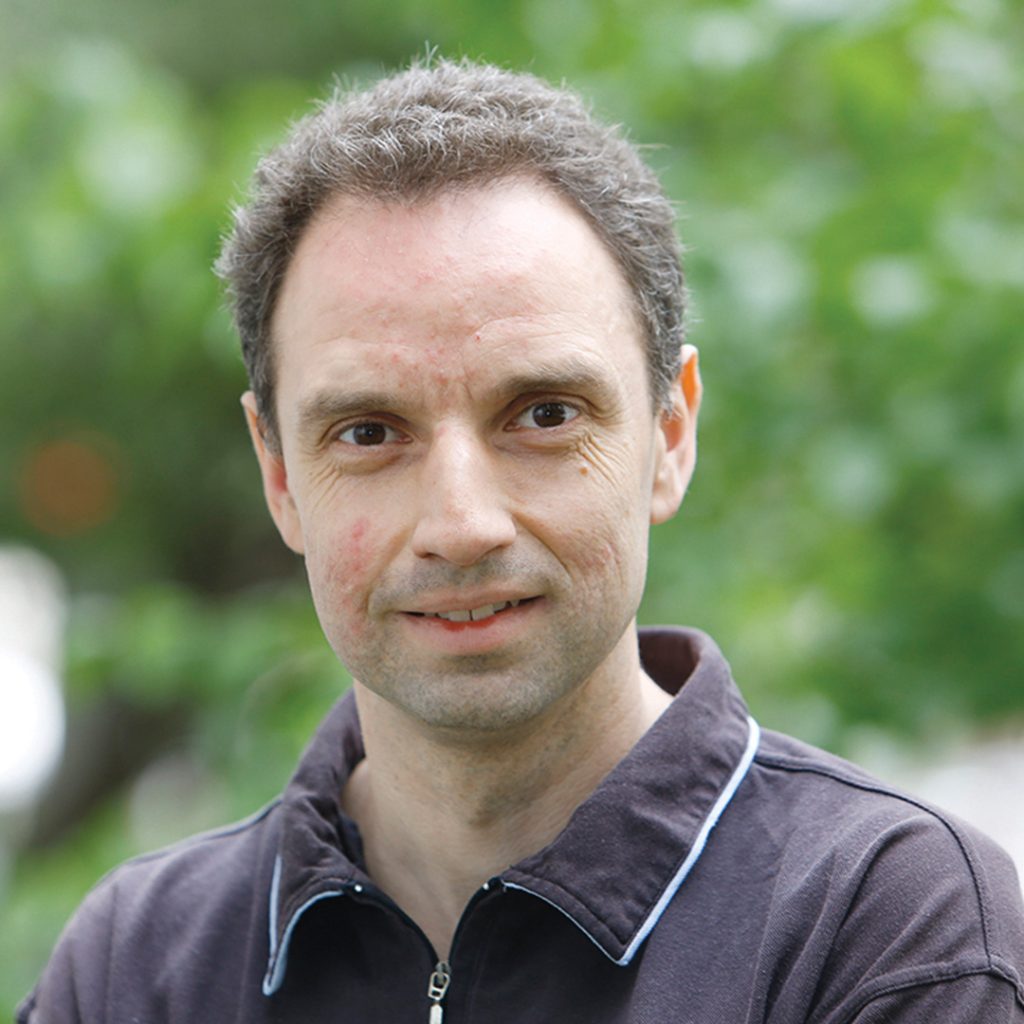

Ulrich Meyer, born in 1971, earned his doctoral degree in computer science at Saarland University and the Max Planck Institute for Informatics in 2002. After working in Hungary and the US, he was appointed as Professor of Algorithm Engineering at Goethe University Frankfurt in 2007. From 2014 to 2022, he was spokesperson of the “Algorithms for Big Data” priority program of the German Research Foundation. His current research covers both theoretical and experimental aspects of processing big data with advanced calculation models.

Manuel Penschuck, born in 1988, earned his doctoral degree at Goethe University Frankfurt in 2021 with a thesis on the scalable generation of random graphs. He is now working at Goethe University Frankfurt as a postdoctoral researcher, focusing on parallel graph algorithms in the presence of storage hierarchies for large networks.

The author

Dirk Eidemüller