Psycholinguistic study on the acquisition and processing of negation

No, this is not supposed to be about parents seeking advice on how to deal with the terrible twos! The following article instead discusses an innovative psycholinguistic project that asks: Why is a negative sentence more difficult to understand than an affirmative one? The project is part of the Collaborative Research Center “Negation in Language and Beyond” (NegLaB).

In German, the simplest way to negate a sentence is to use the word “nicht” (not). This transforms the affirmative sentence “Die Sonne scheint” (“The sun is shining”) into the negative (negated) sentence “Die Sonne scheint nicht” (“The sun is not shining”). This is certainly a very popular construction: If you count the words in German texts, the negation “nicht” always ranks among the Top 20 – with minor deviations. In the frequency list for the German Reference Corpus hosted by the Leibniz Institute for the German Language (IDS) in Mannheim, “nicht” appears in 13th place, for example (cf. https://tinyurl.com/mr4cfxrm).

In view of the frequency with which such negators occur in spoken or written language, that is, in everyday language use, it is rather surprising that negated sentences are often more difficult to understand than their affirmative counterparts. In a classic experiment by Clark and Chase (1972), test persons were shown simple graphics, such as a star above a plus sign: They found it more difficult to rate the negative sentence “The plus sign is not above the star” as true than the affirmative sentence “The star is above the plus sign”.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Negated sentences (“The sun is not shining”) are often more difficult to understand than their affirmative counterparts (“The sun is shining”). Several psycholinguistic projects within CRC 1629 are examining why that is. Core topics are mental processing and acquisition of negation.

- In German, the negator is often at the end of the sentence, which makes comprehension difficult. By contrast, the negator in Spanish, for example, appears earlier in the sentence, which makes it easier to recognize.

- To study the processing of negation in real time, the researchers use various experimental methods, such as measuring eye movements and EEG. These show that understanding negative statements requires complex cognitive processes that are measurable from visual and motor reactions.

- To examine the complex interdependencies between cognition, language and negation, CRC 1629 promotes interdisciplinary exchange between theoretical linguists, psycholinguists and psychologists.

- This goes beyond previous research by taking the cognitive principles of negation processing and acquisition into consideration.

How are perception and language connected?

To identify the difficulties that understanding and acquiring negation present, two fundamental questions need answering: What mental processes are necessary to understand a negated sentence? In what stages do humans learn negation in early childhood? These two questions are central to several projects within CRC 1629 “Negation in Language and Beyond” (NegLaB). In individual projects, psycholinguists and psychologists are working together to examine the acquisition and processing of negation. Embedding these research projects in the overall CRC facilitates productive exchange between projects dealing with the grammar of negation and projects focusing on acquisition and processing. Through this interdisciplinarity, which was envisaged from the outset, CRC 1629 NegLaB goes beyond previous research on negation in a number of ways. What is particularly new is the consideration of the relationship between general cognition and language, as well as the question of how language-specific negation affects its acquisition and processing.

Every language in the world has instruments to turn affirmative sentences into negative ones. But these instruments vary enormously from language to language. To examine this, Project C06, led by Professor Esther Rinke, Professor Sol Lago and Professor Petra Schulz, looks at the position of the negator in German and Spanish. In German, the negator appears relatively late in the sentence and in many instances is even the last word (see example (1a)). In Spanish, by contrast, the negator occupies a relatively early position in the sentence “Juan does not eat his granny’s chocolate” (see example (1b)).

(1a) Juan isst die Schokolade von seiner Oma nicht. (German)

Juan eats the chocolate of his granny not. (word-for-word English translation)

(1b) Juan no come el chocolate de su abuela. (Spanish)

Juan not eats the chocolate of his granny. (word-for-word English translation)

Juan nicht isst die Schokolade von seiner Oma. (word-for-word German translation)

When you hear the German sentence (1a), you assume until the last word that Juan is eating his grandmother’s chocolate. Only with the last word does it become clear that exactly the opposite is meant. In Spanish, by contrast, it already becomes clear from the second word that the sentence is making a negative statement.

Gaze direction shows the comprehension process

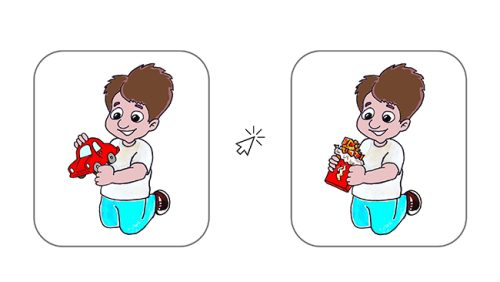

To examine the acquisition and processing of negation, the CRC applies a wide range of methods, with a particular focus on ones that make it possible to record sentence processing in real time, such as the “Visual World Paradigm” (VWP). This method, which is used in several projects, is based on the close connection between seeing and understanding. The researchers analyze the test persons’ comprehension process with the help of a measuring device that records their eye movements. The test persons hear a sentence and at the same time see an image on a computer screen that shows the scene described in the sentence or the objects mentioned in it. The eye tracker is fitted with a high-frequency camera that films the test person’s eyes. From the data obtained in this way, the researchers can calculate, down to the millisecond, which part of the picture the test person is looking at when they hear the sentence.

Experiments that employ this methodology corroborate a close interconnection between the ear and the eye. For example, when we hear the word “chocolate” and there is a bar of chocolate alongside other objects in the picture shown, we immediately and involuntarily look at the chocolate as soon as we have understood the word. This affords interesting possibilities for studying the time course of negation processing. While the test persons listen to the sentences in German and Spanish mentioned above, they are shown the picture just described. In the German sentence “Juan isst die Schokolade nicht”, it can be expected that the test persons will look first at the picture with the chocolate and only look at the alternative picture when they hear the last word “nicht”. But what happens when they hear the Spanish sentence “Juan no come el chocolate” with its early negator? Do they – despite the early negator – look first at the chocolate and then at the alternative object, or do they not look at the chocolate at all? Further experiments will show.

Measuring eye movements is just one of many experimental methods applied in NegLaB. Project C03 (Dr. Carolin Dudschig and Dr. Merle Weicker) uses EEG (electroencephalography) to measure electrical activity in the brain via electrodes attached to the head. This method makes it possible to monitor processes taking place unconsciously in the brain as it digests negative sentences. When a test person hears the negative sentence “Do not press the left button!” and is then asked to press the right button, this takes longer than when they hear the corresponding affirmative sentence “Press the right button!” This observation is not particularly surprising, as the negative sentence only indirectly prompts the test person to press the right button. By measuring brain waves, however, it is possible to study more precisely which processes in the brain cause this delayed reaction. The hypothesis to be validated in Project C03 is that when hearing the sentence “Do not press the left button!”, the motor cortex in the right brain responsible for controlling the left hand is activated first. Due to the negator “not”, this activation must be suppressed and the motor cortex in the left brain responsible for controlling the right hand must be activated instead. The activation of the motor cortex produces familiar patterns in the EEG that make it possible to verify whether this hypothesis is correct.

Most of the psycholinguistic experiments within NegLaB are conducted in one of the psycholinguistic laboratories. The test persons are generally students. The lab experiments are supplemented by online surveys, which are circulated via the internet and run in a browser. In this way, the research teams can reach a far larger target group, with greater variance than the student group in terms of age as well as professional background. This target group is thus more representative of the overall language community.

Literature

Clark, H. H., & Chase, W. G. (1972). On the process of comparing sentences against pictures, Cognitive Psychology, 3(3), 472-517.

The author

Markus Bader, born in 1966, studied German philology, philosophy and psychology at the University of Freiburg and earned his doctoral degree at the University of Stuttgart in 1995. Having been acting professor at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst in 2001/2002, he earned his postdoctoral degree (Habilitation) at the University of Konstanz in 2002 with a dissertation on “Case and Linking in Language Comprehension”. Markus Bader has been Professor of Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics at the Institute of Linguistics, Goethe University Frankfurt, since 2011. His main research interests are language comprehension and language production, with a focus on experimental studies on the grammatical analysis of sentences and calculating their significance.

bader@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding