Mathematics from Ancient Egypt to the coronavirus pandemic

by Annette Imhausen

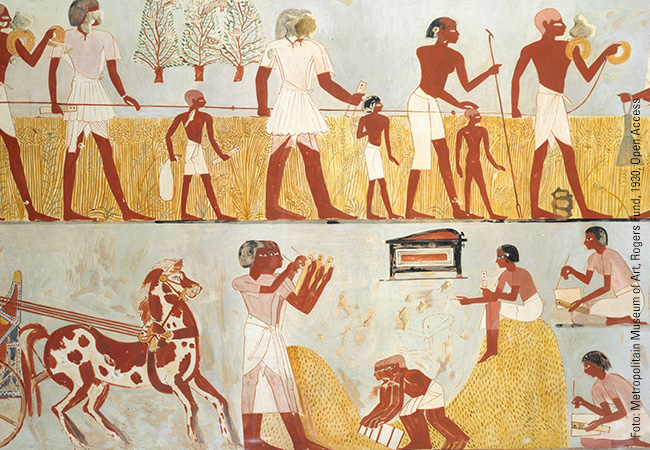

Photo: Metropolitain Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1930, Open Access

We encounter mathematics every day and everywhere. Numbers, units of measurement and structures based on them create fundamental order in our everyday lives. The days of the week, for example, follow a specific order. We expect stores to open (and close) at certain times, just as we hope (at least) that the bus or train will depart and arrive at a certain time. What clothes we put on in the morning depends on how hot or cold it is – a number expressed in °C. We buy, prepare and consume food in certain quantities.

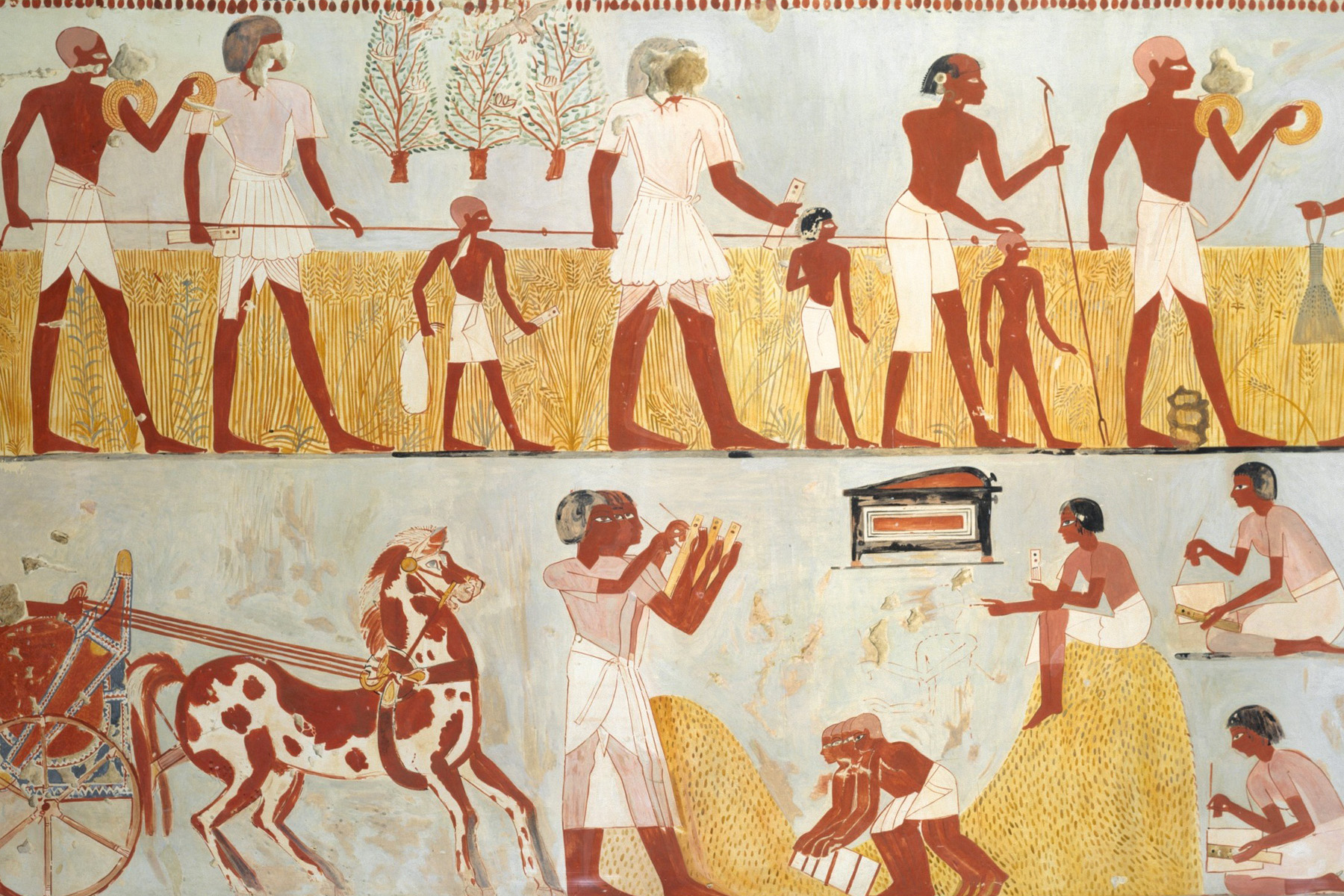

But numbers and the associated systems of measurement that we use to create order in our lives are ubiquitous not only in the modern world. They can be traced far back into history. Scientists have corroborated that numbers and systems of measurement to structure resources of all kinds were used in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, where numbers and letters evolved hand in hand with the development of a hierarchized society in the 4th millennium BCE. In this context, as can be seen in Mesopotamia, the invention of letters was probably only prompted by the development of numbers and units of measurement.

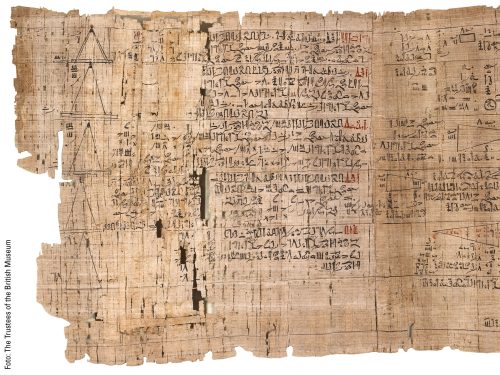

Mathematical techniques were then designed not only to create order with regard to resources but also to control them. These have been preserved in the form of collections of mathematical problems and their solutions from Egypt and Mesopotamia since the second millennium BCE. From such collections, it is possible to draw conclusions about the people living at that time and their values. For example, some problems deal with the allocation of rations, whose amounts are calculated on the basis of social status: The overseer receives a multiple of the amount allocated to the ordinary laborer. Reflected here is the idea of a social order (referred to as Maat in Egyptian) decided by divine intervention, in which everyone had their fixed place and could infer their corresponding obligations and entitlements from this place.

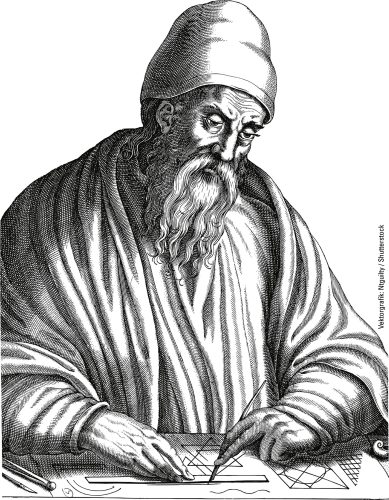

Euclid: As influential as the Bible

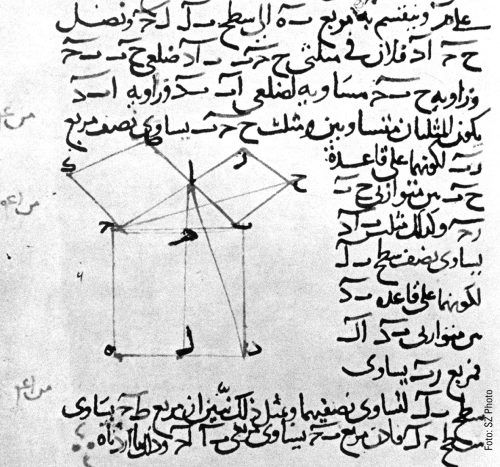

Another development and a new claim to a mathematical order can be found in the mathematical texts of Ancient Greece. The 13 books of the Elements by Euclid (3rd century BCE) are the earliest surviving axiomatic-deductive collection of mathematical knowledge. The term “axiomatic-deductive” describes the structure of this mathematical work: After defining basic objects (such as point, line and circle) and geometric operations (such as connecting two points with a line) in the first book, Euclid first sets down further fundamental requirements for his geometric system in a small number of axioms (principles recognized as correct) and postulates (definitions of further principles). Starting from these principles, theorems and construction tasks follow in the further course of this book, in which only that is used in each case that has already been proven to be correct or possible (in the principles or in preceding theorems and construction tasks). The subsequent books build on this and each deal with specific thematic areas of geometry, such as properties of circles (Book III), proportion (Book V) or geometric series (Books VIII and IX).

It appears that the mathematical system formulated by Euclid was already perceived at the time of its creation as such a clear improvement on other such collections that it dethroned all earlier works, whose existence we only know of through commentators such as the Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus. The excitement about it lasted for centuries, so much so that the mathematics historian Carl B. Boyer, in his comprehensive work A History of Mathematics (John Wiley & Sons, 1991), calculated the number of Elements editions printed since 1482 (work began a long time ago!) to be at least 1,000 and estimated that presumably no other book apart from the Bible has had a comparable influence.

Perhaps it was this success of Euclid’s Elements that gave mathematics a prominent place in the natural sciences – in the words of Galileo Galilei: “The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics.” Those natural sciences whose laws can be expressed with quantitative precision, i.e. mathematically (e.g. physics), were labeled the “exact sciences”. Since then, introducing order into our observations by recording and evaluating data mathematically has become an obvious companion not only in the sciences but also in our everyday lives, as is illustrated, for instance, by the book The Pleasures of Counting (Cambridge University Press, 1996) of the Cambridge mathematician Thomas W. Körner. It begins with a description of how, during the 19th century, the mathematical methods of statistics and mapping helped Dr. John Snow analyze and combat the spread of cholera in London. For the cholera outbreak of 1848/49, he drew up a table of the number of deaths in the various districts, added information about the respective water suppliers and in this way tested his theory that there was a connection between the spread of cholera and drinking contaminated water. During the subsequent epidemic in 1853/54, he mapped the cholera cases and by so doing was able to attribute them to a particular public water pump on Broad Street. On Snow’s recommendation, the pump’s handle was removed – and the number of cholera cases dropped.

IN A NUTSHELL

• Scientists have corroborated that numbers and systems of measurement already existed in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. In the 4th millennium BCE, numbers and letters evolved hand in hand with the hierarchized society. They were primarily used to allocate resources.

• The 13 books of Euclid’s “Elements” (3rd century BCE) are the earliest surviving axiomatic-deductive collection of mathematical knowledge. The excitement about it lasted for centuries.

• Introducing order into our observations by recording and evaluating data mathematically is a matter of course in science and everyday life. Mathematical techniques of statistics and mapping helped Dr. John Snow to analyze and combat the spread of cholera in the 19th century.

• Nevertheless, mathematics also has its limits when it comes to creating order because it gives neither a guarantee nor guidance for its best possible use. This can be seen not least in crises such as the coronavirus pandemic or the climate crisis.

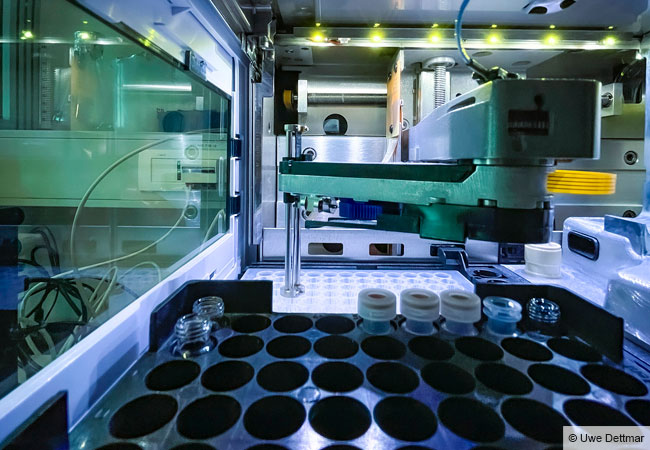

Limits of mathematics in a complex world

Mathematics was also omnipresent during the coronavirus pandemic of the past three years. Many of us still remember how former German Chancellor Angela Merkel explained the exponential growth, or how Lothar Wieler, the then head of the Robert Koch Institute, updated us on the daily incidences and the varying rules and bans associated with them. However, this also revealed the limits of mathematics as a tool for creating order: While, over time, mathematics has delivered increasingly differentiated techniques for recording, introducing order to and thus also interpreting data from our environment, it provides neither a guarantee nor guidance for its best possible use – in the sense of Maat and pharaonic Egypt – because this would have to be negotiated at a different level. These negotiation processes are highly complex and do not depend solely on principles that can be derived from scientific findings and fundamental ethical considerations, but instead also often include an (overly) powerful economic component. This not only became apparent during the coronavirus pandemic, but is also evident in the current handling of the climate crisis.

The author

Professor Annette Imhausen, born in 1970, teaches history of science in the pre-modern world at Goethe University Frankfurt. During a trip to Egypt in the course of her mathematics and chemistry studies (University of Mainz), she discovered her fascination with pharaonic Egypt and began studying Egyptology (University of Mainz and Freie Universität Berlin) in addition to her other subjects. After completing her doctoral degree in history of mathematics (with a dissertation on mathematical papyri, of course!), she was a fellow at the Dibner Institute in Cambridge (Massachusetts) and Trinity Hall at Cambridge (UK) before joining Goethe University Frankfurt in 2009. Annette Imhausen’s research centers on conceptions of mathematics and other areas of knowledge in pre-modern cultures. As Annette Warner, she teaches history of science and ancient history at the Institute of History.