On the handling of confessional differences in the early modern period

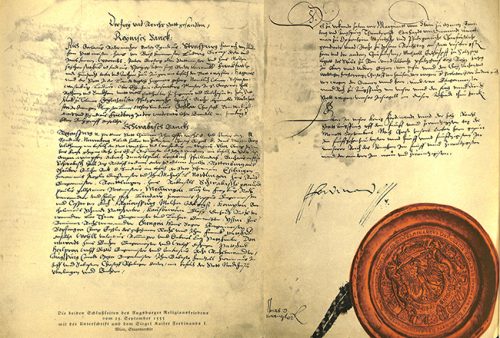

Photo Augsburger Religionsfriede: Source (Wikipedia): Propyläen

In the period following the Protestant Reformation of the early 1500s, religious affiliation played an important role in the Holy Roman Empire – the patchwork of territories that covered much of what is now Germany. And the range of religious groups was vast. Yet even under strict rules and the conviction that one’s own faith was the only true one, people often found ways to live together in peace.

Diversity is one of the positive values of modern society. Whether coffee varieties or cultural events, people or points of view: We like things to be diverse.” These were the opening words of a lecture Birgit Emich, Professor of Early Modern History at Goethe University Frankfurt, delivered in 2014. Now, over ten years later, she observes: “People’s positive attitude toward diversity and the desire for cross-cultural understanding have come under increasing pressure over the past decade. This underlines that they are by no means unwavering goals, not even in the so-called West.” As a historian, Emich is keenly aware of the contextual nature of values: “In the period I study, the years between 1500 and 1800, cross-cultural understanding would have been a rather alien concept to most Europeans, especially in religious matters. Bloody conflicts even arose between the various Christian confessions. And yet, there remained spaces for social interaction across confessional boundaries. I would even argue that cooperation, or at least peaceful coexistence, predominated.” How did people at the time manage to get along despite rejecting one another’s beliefs in a matter as essential as religion? How was religious diversity handled in the early modern period?

Conflict-ridden confessional differences

of the time.

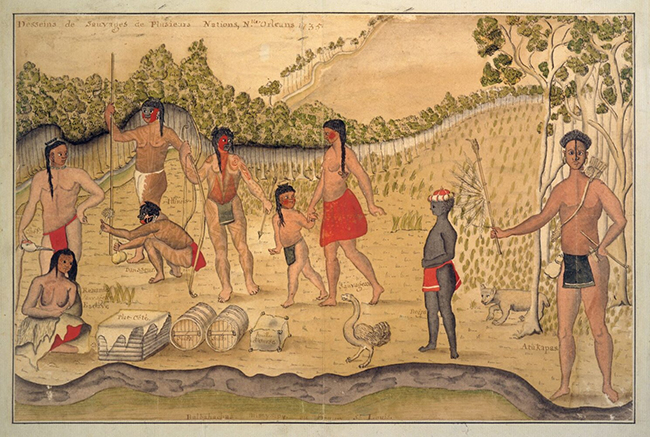

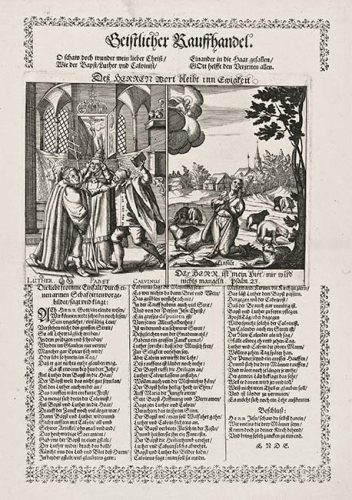

Photo: Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg

The Holy Roman Empire provides a useful case for discussing these questions. Most of the people in this vast empire, stretching from Pomerania to Milan, were Christians. However, with the Reformation of 1517 the question of how to handle religious differences within Christianity gained unprecedented importance. The emergence of the Lutheran Church, and shortly thereafter the Calvinist-Reformed Church, confronted Catholicism with a novel and challenging form of competition. Moreover, tensions arose within the reform movement itself. Numerous smaller and more radical groups emerged, calling into question the increasingly institutionalized Reformation Churches and their hierarchical structures. Among the most prominent of these were the Anabaptists. They rejected the notion of infant baptism and insisted on the conscious acceptance of the Christian faith through baptism in adulthood.

The religious dynamics sparked by the Reformation led almost immediately to bloody conflicts such as the Peasants’ War of 1524/25 and the Thirty Years’ War that raged from 1618 to 1648. “Several factors contributed to the Reformation’s disruptive force, of course – but the violence of these outbreaks is also due to the matter at stake: Religion in the early modern period was a question of either right or wrong,” says Emich. Those who adhered to what was considered the “wrong” faith risked falling victim to eternal damnation. From an early modern perspective, they posed a threat to the entire community should they succeed in convincing others of their beliefs. “This made it both impossible and impermissible to understand those who held different beliefs,” says Emich.

Rulers dictating their subjects’ religion?

However, religion was not only a matter of enormous individual and social significance. The Reformation also triggered specific political development, referred to as “confessionalization”: Secular and ecclesiastical authorities worked hand in hand to advance the development of clearly distinct Christian denominations, also known as confessions. Their aim was that Lutherans, Calvinists and Catholics would not only differ in their teachings but also in their forms of worship, their way of life and their affiliation with specific institutions and hierarchical structures. On top of that, the ruling princes were bent on creating confessional uniformity within their territories, explains Emich: “The core message of the 1555 Religious Peace of Augsburg, an essential document for religious coexistence prior to the Thirty Years’ War, is paradigmatic of this: ‘Cuius regio, eius religio’.” According to this principle, the prince had the authority to dictate the confession of all his subjects. Anyone who refused to submit to the confession of their ruler and who was unable to leave the territory was from then on exposed

to religious persecution – at least potentially.

“That ought to have settled the question of how to deal with the confessional other, as theoretically the problem should not have figured in people’s everyday lives.” On closer inspection, however, it becomes clear, first, that the Peace of Augsburg itself was inconsistent. Imperial cities, for example, were granted the right to observe multi-confessionalism. Secondly, pragmatic considerations made the princes gradually give up their strife for a confessionally uniform territory. As Emich puts it: “Although confessional coexistence was largely prohibited on paper and strictly rejected by doctrine, it was a reality throughout the entire 16th and 17th centuries.” People of the time thus faced the challenge of navigating contradictory and, for confessional minorities, also dangerous waters.

Between belief and obedience

“The most natural coping strategy was presumably that of dissimulation. Once the authorities began to tighten the reins, it was often the only recourse available to those who were not tolerated for their religious beliefs,” says Emich. This is, for example, what happened in the “Lutheran model state” of Württemberg: From 1534 on, pastors had to report anyone who did not attend sermons and communion. Inquiries were conducted with the purpose of identifying dissenters and leading them back into the fold. At worst, dissenters faced imprisonment, confiscation of property, banishment and – at least in theory – the death penalty. Many Anabaptists living in Württemberg thus saw their only chance in keeping a low profile. This often meant a balancing act between obedience toward the authorities and their personal beliefs. A common way to straddle the line was to avoid Lutheran communion by offering innocuous excuses, such as being confined to bed.

At first glance, dissimulation has little to do with religious coexistence or even mutual understanding. “There are, however, two things that I find noteworthy,” says Emich. On the one hand, successful dissimulation required a certain degree of goodwill from the other party: It required that not every excuse would be scrutinized, and that there were unsuspicious individuals willing to cover for the others’ pretexts. “The complaint of a Lutheran pastor who maintained that it was impossible to deal with the Anabaptists in his village because the entire village court was sympathetic to them, shows that cross-confessional solidarity did indeed exist,” observes the historian. On the other hand, Anabaptist doctrine explicitly allowed dissimulation, even outward recantation, in emergency situations. “In so doing, the doctrine took account of the fact that the reality of life sometimes necessitated a certain degree of ambiguity – of operating in gray areas. For me, it is precisely this willingness to accept ambiguity and to navigate those gray areas that represents the key to peaceful religious coexistence in the early modern period,” says Birgit Emich.

IN A NUTSHELL

• After the Protestant Reformation, religious affiliation played an important role in the Holy Roman Empire. This led to conflicts such as the Peasants’ War and the Thirty Years’ War. Belief was regarded as a question of right or wrong, which provoked deep religious tensions.

• The rulers enforced confessionalization. By virtue of the 1555 Religious Peace of Augsburg, they had the right to dictate their subjects’ religious orientation. This principle, known as “Cuius regio, eius religio”, could lead to the persecution of religious dissenters.

• To escape persecution, people living

in religiously homogenous territories were in many cases obliged to dissimulate. Anabaptists and other minorities often kept their religious beliefs to themselves and adjusted their behavior in order to avoid conflict.

• Although there was no genuine religious tolerance or understanding

for other denominations, there were nevertheless moments of cross-confessional solidarity in people’s everyday lives and a willingness to cooperate.

The rosary as a means of disguise

Traveling, of course, also required navigating gray areas. This is why Protestants venturing into Catholic territories often carried a rosary as a means of disguise. Even the Enlightenment thinker Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a Protestant himself, is said to have occasionally disguised himself in this way while traveling. More striking still, some travelers engaged in the practices of another confession even when there was no pressing need to do so. A well-documented case is that of a Calvinist from Alsace who visited Catholic pilgrimage sites in Italy without this compromising his self-identity as a Reformed Christian. “Perhaps we can understand this as meaning that despite all the efforts by the authorities to draw firm boundaries, these boundaries were not equally important to believers in all situations,” surmises Emich: “When away from home, the crucial point may sometimes have been that one was among other Christians whose religious practices one could resort to when those that suited one’s own confession were unavailable at that precise moment.”

In other situations, a very clear awareness of confessional differences might have been present, yet it was not considered crucial at that moment because of other shared convictions. In Emden, for example, a Reformed woman asked the church council in 1560 whether she should still participate in communion even if her Catholic husband did not allow it. The church council supported the woman’s position insofar as it replied that she should obey Christ more than her husband. However, an additional statement softened this apparent encouragement to attend communion by noting that it would be best if her husband also agreed to her attendance. If he did not, the woman was advised to stay at home. Confessional interests evidently did not carry as much weight as gender hierarchy, even for the Emden church council. “We might find this questionable today. But it is important,” emphasizes Emich: “Even in a society in which religion held such a central place as in early modern Europe, there were other frameworks of social order that also held the community together and could serve as a bridge.”

Anabaptists as guarantors for newly-converted Lutherans

Equally curious is the case of Jan van Bellen, an Emden citizen who converted several times throughout his life: In order to be accepted into the Lutheran Church, he asked the church council to make inquiries about his way of life with his former Anabaptist congregation – which the council indeed did. “This means that the church council recognized the Anabaptists as an authority when it came to deciding whether someone was a ‘decent person’ – despite their confessional differences. This suggests that there were fundamental values which were shared despite religious differences.”

The willingness to operate within gray areas or to emphasize commonalities while setting aside dividing issues should not, however, be mistaken for religious tolerance – or even religious understanding, warns the scholar. For as soon as the authorities became involved and insisted on compliance with the rules, there was only right and wrong in religious matters, as has been shown time and again. It would likewise have been unthinkable to admit that one considered confessional matters “not particularly important” – or that one was religiously undecided. And of course, one must not lose sight of the difficult position of all non-Christians.

Nevertheless, for Emich, the examples demonstrate that it was possible to get along with people whose beliefs one did not share – and consequently did not want to understand. Cooperation of this kind succeeded because there were other interests and values people had in common, as well as areas that were at least implicitly excluded from the strict rules. “As ideological trenches are currently growing again, I think it is important to keep these possibilities in mind – especially if we also become aware of the fragility of maneuvering within gray areas,” says Emich. That is why she wants to gain a better understanding of the specific situations in which this willingness toward ambiguity dwindled. A future project on confessional tipping points in the early modern period aims to examine when and how peaceful cooperation gave way to violent conflict – and what factors, beyond the authorities’ insistence on compliance with the rules, contributed to these shifts.

About Birgit Emich

As Professor of Early Modern History, Birgit Emich has taught and conducted research at Goethe University Frankfurt since 2017. Among other tasks, she is one of two directors of the DFG-Centre for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences “Polycentricity and Plurality of Premodern Christianities”, a Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Her current research explores how religious plurality

was possible in the early modern period even though different religious groups claimed exclusive rights to the truth and attempted to assert these claims through legal means and political power.

emich@em.uni-frankfurt.de

The author

Louise Zbiranski is Outreach Officer for the research group “Dynamics of Religion” and coordinates the work of the “Schnittstelle Religion”, a platform for research communication.

l.zbiranski@em.uni-frankfurt.de

To the entire issue of Forschung Frankfurt 1/2025: Language. The key to understanding