How supercomputers of the future will look

The Center for Scientific Computing at Goethe University Frankfurt is currently operating a cluster with 25,000 CPU cores (processors) and 880 AMD MI50 GPUs (graphics processing units). The CPU performance is two petaflops per second, the GPU performance is six petaflops per second. A petaflop is equivalent to one quadrillion operations per second. An upgrade is planned for 2023, the procurement process is underway. Lippert: “Our expansion philosophy is clear: we will continuously renew the high-performance system in line with the needs of research and maximum energy efficiency, instead of completely replacing the system in cycles of four to five years, as is otherwise usual with supercomputers.” Photo: Jürgen Lecher

When many processors are grouped together to form a supercomputer, we call this a high-performance computer. Goethe University Frankfurt has such a computer cluster and will soon be adding a quantum computer, with the perspective of tackling computing tasks which are currently unsolvable.

Leonardo, Fugaku and JUPITER are their names, and they have enormous computing power. They are all supercomputers, rack upon rack of IT cabinets housed in bare rooms in university buildings, flashing mysteriously while doing their gigantic computing jobs. Together, they form a high-performance computing cluster. In the world of high-performance computing, new records are set on a regular basis. The current No. 1 on the Top500 list, the Frontier supercomputer at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the US, was the first to officially break the legendary 1 exaflop speed barrier. An exaflop is one quintillion – 1 000 000 000 000 000 000 – computing operations per second (or one trillion in the European numbering system). Some of the most complex computations can be performed with this immense processing power: climate models that reach well into the 21st century, or simulations of the spatial structures that the coronavirus spike protein is able to assume. Supercomputers are often set to work on the big issues. How can we save the climate? How can we fight pandemics? However, the complexity of the tasks continues to grow, which is why it takes more than just ever more operations per second. High-performance computing needs new ideas for using the combined processing power of several supercomputers in a smart way.

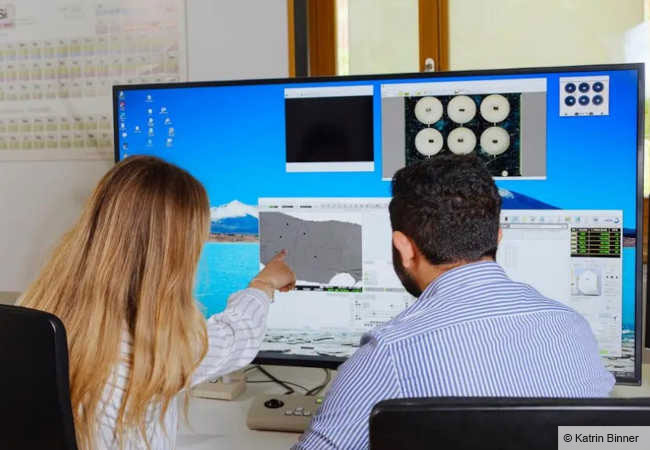

Such an idea is currently being put into practice at the Centre for Scientific Computing (CSC) of Goethe University Frankfurt. This is part of the National High Performance Computing (NHR) alliance established in 2021 to bundle the resources and competencies of university high-performance computing – something like the elite of German supercomputers. The CSC computing facility currently has a performance of a few petaflops – a petaflop equates to one quadrillion operations per second. Rather than sheer computing power, the fundamental concept is more important. This is known as Modular Supercomputing Architecture (MSA). Thomas Lippert, physicist and computer scientist, who is one of the trailblazers of this concept, wants to build a high-performance computer of a special kind in Frankfurt. He explains what MSA can basically do as follows: “It enables the parallel processing of computational problems at the system level, we also call this functional parallelism.” But why is it useful? Imagine that a computing task consists of two parts that can only be easily solved on two parallel computers in sequence or at the same time, but which have a very different system architecture.

Quite spectacular: in 2021, IBM’s “Quantum System One” at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering in Ehningen was inaugurated as Germany’s first quantum computer. Photo: Andrew Lindemann/IBM

Mixing and matching computer architectures

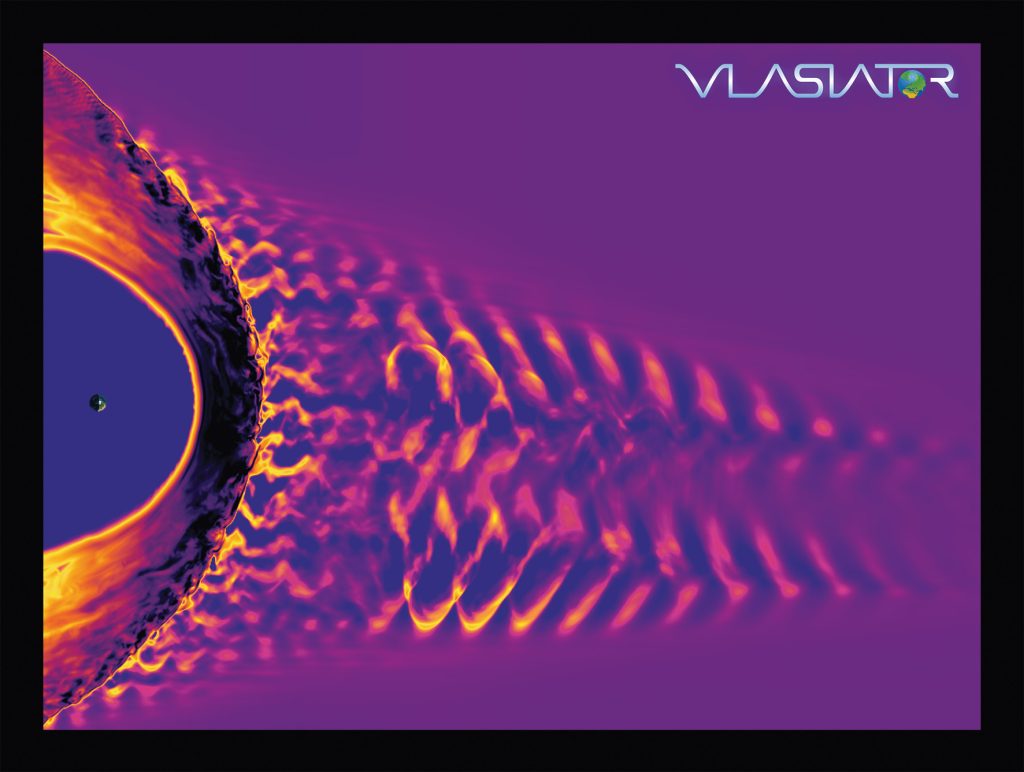

A CPU cluster and a GPU cluster, for example, have such different architectures. CPUs, central processing units, have a limited number of cores and are less suitable for highly parallel data processing.By contrast, GPUs, or graphics processing units, consist of thousands of very small cores that work on a problem at the same time. Two fundamentally different ways of working, but the modular architecture brings them together. “It is a simple concept and provides the necessary tools and software environments so that both systems can be used at the same time,” explains Lippert. “This optimizes the entire process in terms of time and energy consumption.” How this works in practice can be seen from computer simulations for the European Space Agency’s space weather observatory that model solar winds – charged particles (plasma) ejected in solar flares – and how they interact with Earth’s magnetosphere. The simulation system’s workflow requires two solvers. The field solver calculates the development of Earth’s electromagnetic field – this part is done by a CPU cluster. The particle solver calculates the motion of the charged particles in the electromagnetic field calculated by the field solver that runs on a GPU cluster.

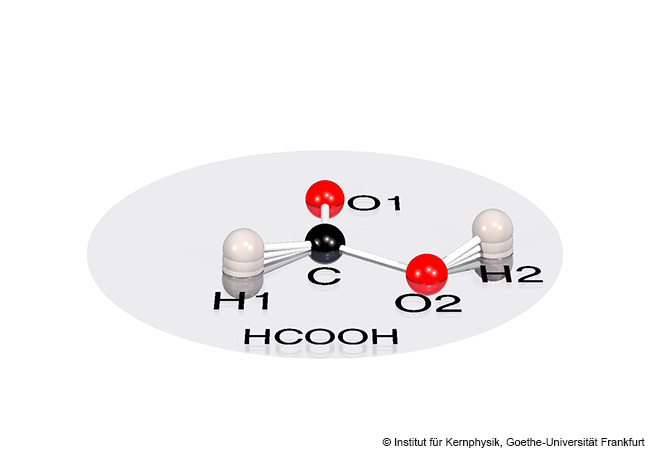

Back in Frankfurt, the CSC plans to divide computing tasks in a similar way: a first pilot quantum computer module will be installed this year, teaming up classic high-performance computing and quantum computing in the future. But this cannot be achieved without further ado, as quantum computers work differently to classical computers. The latter process information as bits (binary digits) which are always in exactly one of two possible states: 0 or 1. Quantum computers, on the other hand, make use of the seemingly bizarre laws of the quantum world, that is, a world with the smallest of particles: photons or quarks. Quantum computers process information in quantum bits or qubits. These can be 0 and 1 at the same time, allowing for an infinite number of possible states in between. The coefficients can even be complex numbers that go beyond real numbers. Qubits are comparable to a rotating coin: it shows not only heads or tails, but all possible “faces” at once.

IN A NUTSHELL

- Very complex computations need powerful supercomputers, for example for global climate models, models of flexible biomolecules or large-scale AI applications.

- In the future, quantum computers and conventional computers will be combined to form supercomputers.

- Modular architecture draws together the strengths of both types of computers.

Modular architecture

This feature is known as superposition and forms the mathematical basis for the potentially exponential growth of computing power inherent in quantum computers. While in classical computers the computing power increases linearly with the number of computing modules, the computing power of a quantum computer increases exponentially with the number of qubits used. Lippert explains this in numbers: “For a state with two qubits, you need four complex numbers for characterization, but for a state with three qubits, you don’t need six, you need eight. And 50 qubits do not encode 100 numbers, but 2^50 complex numbers, that is, 1 125 899 906 842 624, over a quadrillion states.” In principle, this allows quantum computers to solve highly complex problems that classical digital computers would fail to solve on their own. It would take a “normal” computer 10,000 years to calculate the same thing that a quantum computer needs only 200 seconds to do – as the result of a spectacular experiment revealed.

Despite all their differences, both types of computing can be easily coupled, which is the task of the modular architecture. “This will allow our quantum computer and our supercomputer to work together on a problem – and for each computer to tackle the tasks that are most suitable for its architecture,” says Lippert. Hybrid algorithms are used that are based partly on classical high-performance computing and partly on quantum computing. “In the future, we will need quantum algorithms wherever very difficult optimization problems need solving. For example, when planning traffic routes or flight schedules. The key advantage lies in the fact that quantum optimization can be repeated very quickly. We are then able to re-optimize and control the traffic situation in a city with millions of inhabitants every few seconds.” This will lead to energy savings and protect the environment, he says.

Supercomputers of the future

Lippert makes an important distinction: “Quantum computers are not built to replace conventional high-performance computers. They are quite weak in the field of classical arithmetic and can only be used to a very limited extent. Rather, we are building them to gain access to areas where we simply cannot compute yet.” The classic supercomputer will continue to take on most of the tasks, he adds.

It is not yet known which quantum computing technology the CSC will use. After all, qubits can be generated in different ways, for example with trapped ions. In this process, the charged particles are trapped in electric fields, irradiated with microwaves or lasers and thus brought into different states. This is how the qubits are created. The decision at the CSC has not yet been made, but there are “very interesting candidates”, and Lippert can already reveal a unique benefit: the targeted pilot system can be operated at room temperature. A major advantage over the quantum computers that only run at temperatures close to almost absolute zero, that is, -273.15 °C.

It will take a while to complete the modular architecture at the CSC, but for Lippert it is already clear that the future of high-performance computing lies in this approach. “We urgently need MSA to meet computing demands that are growing exponentially in the field of simulation, digital twins or large-scale AI applications like the foundational language models.” This would hopefully allow researchers to find solutions to the major challenges facing society today, he says, such as pandemics, the climate or energy.

About

Thomas Lippert, physicist and computer scientist, has developed and patented the modular architecture for supercomputers. He has been Professor for Modular Supercomputing and Quantum Computing at the Institute of Computer Science of Goethe University Frankfurt since August 2020. He is also director of the Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC) at Forschungszentrum Jülich, which is collaborating with the CSC in Frankfurt. Jülich will be home to JUPITER, Europe’s first supercomputer in the exaflop range. Lippert is also on the board of directors of the John von Neumann Institute for Computing (NIC), which provides supercomputer capacity for research projects. Goethe University Frankfurt is due to become a member of the NIC.

The author

Andreas Lorenz-Meyer, born in 1974, lives in the Palatinate and has been working as a freelance journalist for 13 years. His areas of specialization are sustainability, the climate crisis, renewable energies and digitalization. He publishes in daily newspapers, specialist journals, university and youth magazines.

andreas.lorenz-meyer@nachhaltige-zukunft.de