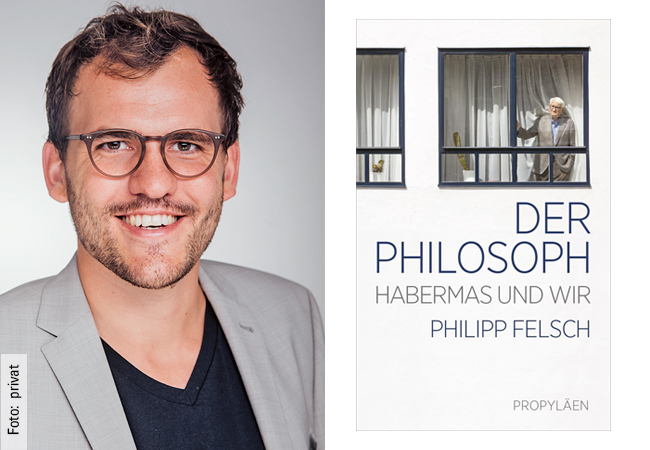

Philipp Felsch’s book Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir, discusses contemporary and intellectual history and its relation to the work of a great Frankfurt philosopher. A review by Felix Kämper

In his new book, cultural scientist and essayist Philipp Felsch paints a philosophical and political portrait of the most important living proponent of Frankfurt School Critical Theory. The 22 sections of Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir [The philosopher: Habermas and us] take the reader on a loosely chronological tour of different aspects of Habermas’ work. At times, the text focuses on his public interventions, at others on his teaching and writing style, and often also on intellectual friendships and enmities – and the transitions from one to the other. While the book does mention some basic theoretical ideas, by shedding light on contemporary political events in Germany, Felsch also looks beyond Habermas as a philosopher. Depending on the angle, he offers readers a flip image describing both the critical theorist’s own intellectual history as well as the political history of intellectual thought in Germany, whereby Felsch explains the different aspects like foreign words whose meaning emerges from the context. He writes about combinations of factors without claiming to be exhaustive.

An unpretentious thinker

Felsch’s previous books focused on Habermas’ antagonists: the French postmodernist authors in The Summer of Theory (2015), and those who prepared the way for them in How Nietzsche Came in From the Cold (2022). After reading the first section of Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir, however, one gains the impression that the author has switched sides. Felsch recalls a visit he paid to Habermas at his house in Starnberg, which left him impressed by the unpretentious manner of this prolific professor of intellectual history. Apart from this initial insight, there is nothing particularly reverential in this portrait. Felsch traces back the reasons for Habermas’ standpoints without adopting a position on them himself. There are only a few places where he allows his own judgment to show through in this analysis of the dual role played by Habermas, “who like virtually no other philosopher targeted the supratemporally general, while responding as a public intellectual … to a specific historical situation” (17).

Felsch follows this with a successful illustration of how the young Habermas’ desire for a new political start that goes beyond satisfying the yearning for normality in post-war society is linked to his turning away from the philosophy of Heidegger and toward Jewish thinking. Like Theodor W. Adorno, for example, he finds himself living in an “upside-down world” (19) that requires detailed explanation. At the same time, the paths Habermas pursued in his social criticism diverge from those of his teachers. Alongside innovative substantive course changes, he eliminates its suggestive and ethical aspects in order to appear less like a “producer of world views” (35). Although this style of thought goes down well in New York, in Frankfurt he becomes alienated from the student movement. Habermas, whose “inclination to confrontation and polemics” (55) is directed against what he calls the movement’s bogus revolutionary drive, is considered too moderate and liberal by many ’68ers.

Communication and criticism

Habermas makes the crucial academic shift to linguistic philosophy several years later upon becoming director of the Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World. The normative reference point in his approach is the ideal speech situation. As Felsch sets out, the idea behind this is not the anticipation of a discourse free of coercion, but the indispensable presupposition of communication. To a certain extent, such an approach could help neutralize the sting in the criticism of insufficient “reality content” (72), on which such disparate academics like Ralf Dahrendorf, Robert Spaemann, Niklas Luhmann, Michel Foucault and Dieter Henrich concur. In 1981, Habermas’ considerations culminate in “The Theory of Communicative Action,” which Felsch sees as very informative, and rates as an attempt to take away “the sovereignty of interpretation” (90) from these conservatives, who view the German Autumn as a reason to agitate against those expressing social criticism. [Editor’s note: The term “German Autumn” refers to a series of events in Germany in 1977, including the kidnapping and murder of Hanns Martin Schleyer by members of the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the hijacking of Lufthansa Flight 181 by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.] Habermas’ diagnosis of a colonialized lifeworld met with strong opposition – from conservative and liberal contemporaries to Marxists, among whom “the motif of the state-supporting thinker” (98) became widespread.

Felsch, however, pursues this motif somewhat too enthusiastically. While the idea that Habermas saw the Federal Republic of Germany increasingly as an “epoch-making success story” (76) and as a result relegated the system question may be correct to some extent, saying “reconciliation” took place in the 1980s (109), and that Habermas actually saw in this a “concrete utopia” (161 f.), is a distorted representation. At this point the author succumbs to pure black-and-white thinking that seeks “security in the false clarity of dichotomies created by force” – a type of thinking that Habermas sharply condemns in his 1983 defense of civil disobedience “against the authoritarian legalism in the Federal Republic of Germany”.

The remark that his attitude is virtually indistinguishable from the “gesture of a right Hegelian” (172) also constitutes a massive exaggeration. As such, the first chapter of “This Too a History of Philosophy” makes it clear that Habermas is still keeping a healthy distance from transfiguring-reconciliatory types of thinking.

Lessons from the past

The debate with which Habermas probably made the greatest name for himself in German intellectual history is the Historikerstreit (“historians’ dispute”) over the singularity and significance of the Holocaust for national consciousness. Felsch interprets Habermas’ broadside fired against the revisionist tendencies of some historians as a “coup” (123) and thus as a shining example of strategic action. This is also the standpoint based on which he analyzes the more recent debate on the effects the violence in the Middle East has had on Germany – a debate in which Habermas has once again taken up a position. Felsch questions whether the singularity thesis can be reconciled with the principle that the dignity of each human being is of equal value. While it is true that, due to the obligations arising from the crimes against humanity during the Shoah, a wrongly understood singularity and solidarity can lead one to neglect other obligations, this does not have to be the case. Acknowledging the horrors of National Socialism and the mandate to prevent a repetition of Auschwitz does not have to make one blind to other crimes, including those committed by Israeli politicians or the Israeli military. As long as historical responsibility is not reduced to an alibi, there is no apparent reason why it should contradict a universalistic attitude.

The problem of German national consciousness acquired new urgency when the Berlin Wall came down. Habermas, who saw constitutional patriotism as the only safe option, spoke out in favor of “an all-German constituent assembly” for reunification (164). To stem future nationalist tendencies, from then on he also appealed for European integration. On both levels, as Felsch correctly points out, he was hoping that deliberation would result in a transformative recursive formation of identity. After considering Habermas’ views on war – primarily the war in Ukraine – the portrait ends with another meeting between the two in the fall of last year. The enlightened philosopher’s gloomy contemporary diagnosis reveals just how frustrated he is with current developments. But contrary to Boethius, who sought consolation from philosophy in his dark hours, Habermas does not find theory a good consolation for tragic events.

Reflections on contemporary history

Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir is a lively book that opens up exciting ways of accessing one of the world’s most important philosophers through contemporary history. Although the texts lack some of the personal insights necessary for a popular portrait, the author skillfully compensates this by describing Habermas’ uneasy relations with other intellectuals, including Martin Walser, Karl Heinz Bohrer and Hans Magnus Enzensberger. An interesting alternative examination of Habermas’ correspondence could have focused less on investigating philosophy and more on connections with contemporary history: what were the conditions that facilitated Habermas’ project? Which structures and coworkers did he rely upon for him to develop such prodigious productivity? Here one might consider, for instance, his statement that he required the security of a “bourgeois life-form” so as “to be able to think without too much fear” (105). There are certainly subtler incentives to adapt than fear (as shown not least by Habermas’ postmodern counterpart Foucault). One way or the other, if one takes these insights seriously, the question arises of what one should make of current developments, including the planned reform of the Academic Fixed-Term Contract Act.

You can hear more about Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir in “Book Talk,” a discussion between the author Philipp Felsch and Martin Saar, Professor of Social Philosophy, which will take place on April 30, 2024, at 6 p.m. in the Eisenhower Room in Campus Westend’s IG Farben Building. The Goethe Lectures Offenbach on the topic of “Democracy in times of regression” will commence in the Klingspor Museum in Offenbach on May 6, 2024, at 7 p.m. with Rainer Forst, Professor of Political Theory and Philosophy and director of the research center “Normative Orders.”

Felix Kämper is a research assistant at Goethe University’s “Normative Orders” research center. His work focuses on normative and contemporary diagnostic questions of society’s relationship with the environment. His dissertation bears the title “Vernunft und Natur: Kritische Theorie der Gesellschaft und ihrer Umwelt” [Reason and nature: a critical theory of society and its environment].