On the investigation of cosmic catastrophes

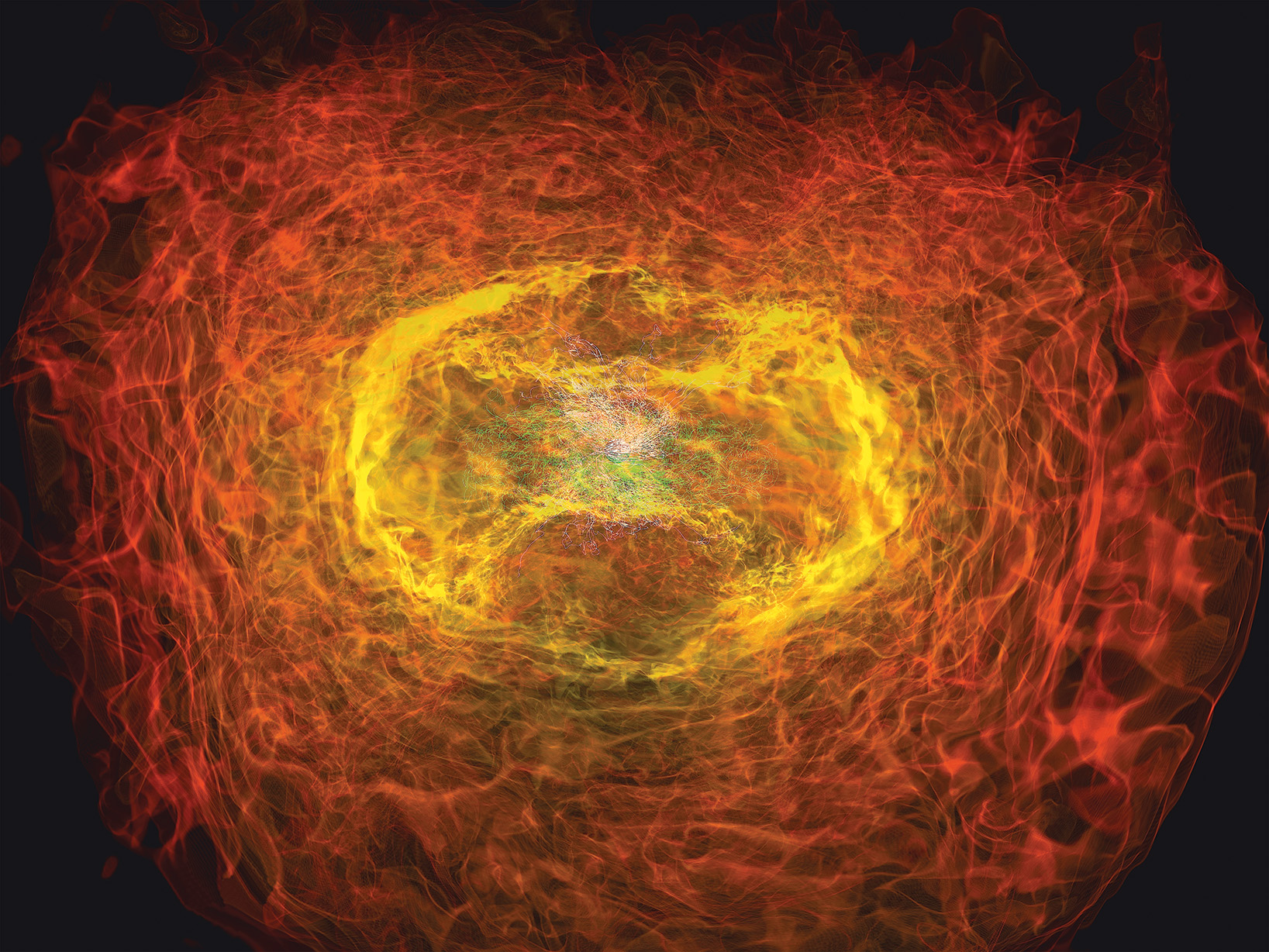

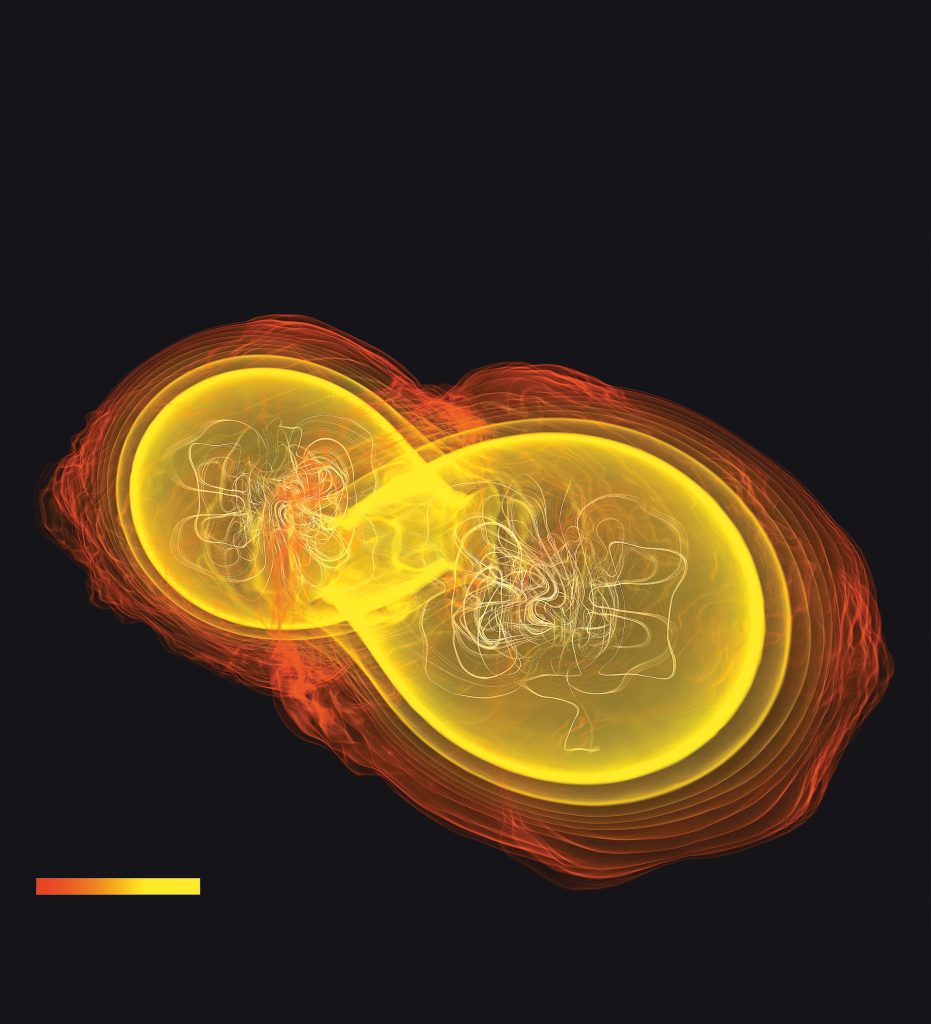

This simulation-based calculation shows that the magnetic field (white and green lines) is still chaotic a few milliseconds after two neutron stars have merged. In the following milliseconds, it forms a jet, which is the prerequisite for emitting a short gamma-ray flash, known as a blitzar. Photo: L. Rezzolla, M. Koppitz, GU/AEI/Zuse

When neutron stars or black holes collide, they change the fabric of space and time. The gravitational waves emitted by such collisions are measurable on Earth. Luciano Rezzolla at the Institute for Theoretical Physics of Goethe University Frankfurt is investigating what such signals from the depths of space reveal about our world.

16 October 2017 could have been a day of perfect triumph for theoretical astrophysicist Luciano Rezzolla. Why? Because on that day researchers at LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in the USA, and Virgo, its European counterpart, announced that they had once again recorded gravitational waves – strong deformations in the fabric of space and time that reach the detectors on Earth as tiny ripples in the fabric of space and time – from the depths of space. In the case of the first signal ever detected and all signals measured during the previous two years, the gravitational waves could be traced back to the merging of two black holes, that is, to the collision of two objects that constitute the largest concentration of mass in the smallest area.

This time, however, the signal measured represented the first gravitational waves from the collision of two neutron stars, two objects whose mass is also extremely condensed, although not as extremely as in the case of black holes, but that are made of matter and have a hard surface. Making use of complex theoretical calculations based on Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, Luciano Rezzolla (and other scientists) had already predicted such gravitational waves back in 2010. Measured data were now finally available which confirmed the theoretical models.

Colorful and aesthetic

Something, however, rather dampened Rezzolla’s good mood: just two weeks before that day, his elaborate research proposal, which would have helped him to launch a major project on neutron-star research, had been rejected. The reviewers argued that it was highly unlikely that measuring the gravitational waves of colliding neutron stars would be possible in the near future. “Really unfortunate,” says Rezzolla – if only the authors of the review had been a bit more optimistic!

IN A NUTSHELL

- The existence of gravitational waves, which were measured for the first time in 2015, was predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years earlier in his general theory of relativity.

- Collisions of extremely dense celestial bodies (such as neutron stars and black holes) emit gravitational waves.

- The interaction of theoretical calculations and actual measurements is used to study cosmic catastrophes as well as the origin of heavy elements such as gold.

Neutron-star collisions are key to our understanding of how matter behaves under extreme conditions of density and gravity, and how the heavy elements are produced that make up our world. It might be the case that in these collisions matter is compressed to such an extent that it disintegrates into its elementary components. This can be seen, for example, in Rezzolla’s simulation calculations, which he performs with the help of supercomputers: on his screen, the cosmic catastrophes unfurl a lively, colorful and aesthetic display of vortices and multiform spheres in shades of yellow, orange and red. “What we’re seeing here is math,” explains Rezzolla, “it’s just a different way of presenting things than rows of numbers.” With these simulations, Rezzolla was able to show that certain features in the gravitational waves coming from the collision of two neutron stars could prove the possible production of a “soup” of elementary particles, known as quark-gluon plasma.

Einstein is the starting point

Two years ago, Rezzolla, together with colleagues from Goethe University Frankfurt, TU Darmstadt, GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt and Giessen University, launched the ELEMENTS Research Cluster to study neutron stars. They want to know: What does the interior of neutron stars look like? In which state is the matter during the collision? Does it exist as a plasma of elementary particles (quarks)? Are collisions a precondition for the formation of heavy elements such as gold or platinum? Rezzolla and his team want to contribute to answering these questions.

Their starting point was Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which was presented as long ago as 1915. “That of general relativity is a beautiful theory,” says Rezzolla. “It is beautiful in terms of mathematics, and it is beautiful because it explains the effect of gravitation under only one assumption: there is an upper limit to propagation velocity and thus light has a maximum speed.” To Rezzolla, this assumption seems logical because “otherwise we would expect things to be able to change instantaneously. We humans would then probably be more like ghostly apparitions that could appear everywhere and at any time.”

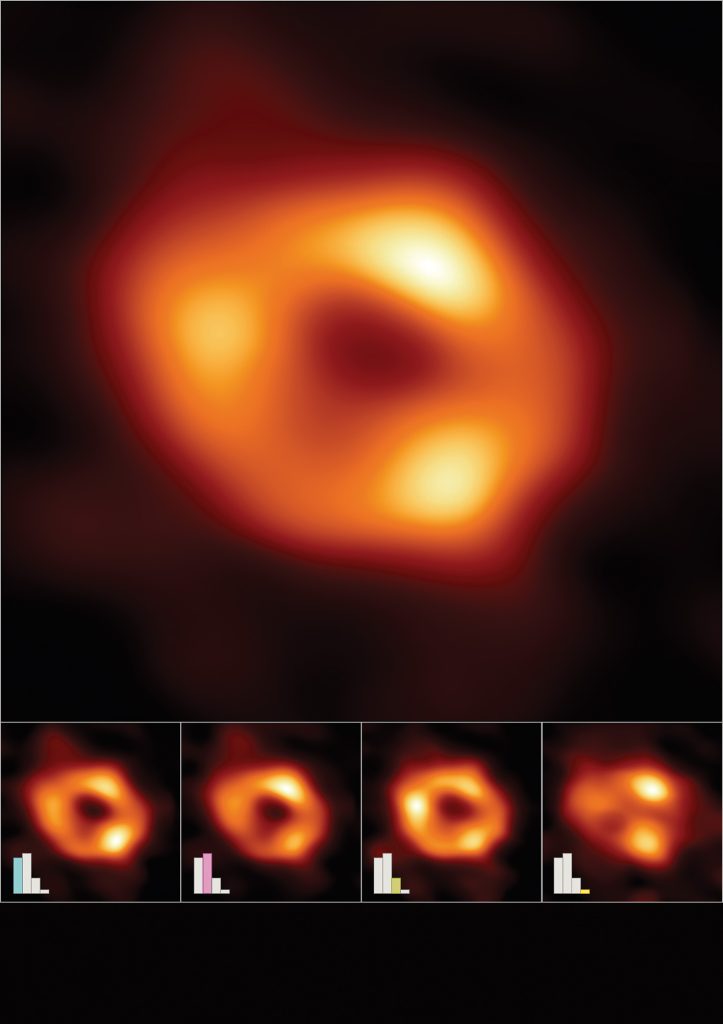

For the first image of the black hole at the center of our Milky Way (top), Luciano Rezzolla and his colleagues from the international “Event Horizon Telescope” (EHT) research collaboration analyzed vast amounts of radio wave data and calculated thousands of images that all matched the data. The images were averaged and divided into four groups (small images). Most of the images showed a ring around the black hole, as expected from theoretical calculations. Photo: EHT Collaboration

Movement along the curvature

Some of the implications of Einstein’s theory, however, cannot be understood so intuitively: that space and time are inseparable and that masses distort this spacetime fabric. From this it follows that gravitation does not derive from the mutual attraction of masses – a theory developed by Isaac Newton in the 17th century and which for 250 years splendidly explained almost all observable motional phenomena. Only when astronomers measured Mercury’s orbit exactly did small cracks appear in the facade of Newton’s theory: its orbit deviates slightly but significantly from the path it is supposed to follow according to Newtonian principles. Einstein’s theory, on the other hand, was able to explain this phenomenon.

According to Einstein, the distortion of spacetime causes masses to move along its curvature. Rezzolla compares spacetime with a bed sheet. If you place a heavy stone on it, the stone deforms the sheet to form a sort of “bowl”, curving the “spacetime sheet”. A marble placed on the edge of the bowl would follow the curvature of the sheet and roll towards the heavy stone. What Newton had interpreted as attraction through the mass of the heavy stone, Einstein attributed to the curvature of spacetime (that is, the spacetime bowl).

Flashes from space

However, not only masses but also light and time are influenced by gravitation. The best way to illustrate gravitational waves is to replace the bed sheet with a rubber one, like the children’s trampolines we have in our gardens: when the heavy stone is set in motion, the rubber sheet will start to oscillate, just like gravitational waves vibrate when neutron stars and black holes move. The greater the stone’s mass and the more its speed increases, the stronger the vibrations and hence the gravitational waves. Therefore, when binary systems of neutron stars or black holes orbit around each other faster and faster, they emit increasingly strong gravitational waves, which, in turn, reveal something about their mass and motion.

Since measuring gravitational waves is now possible, they could in future also possibly corroborate another of Rezzolla’s theories, one of his favorites. Of course, this one also has to do with neutron stars and black holes. The starting point of the whole story was a coffee break during an astronomy congress in 2014 in Bonn, to which he had been invited by his colleague Heino Falcke from Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands. Shortly before, Rezzolla and Falcke, together with astronomer Michael Kramer from Bonn, had laid the groundwork for a global collaboration which aimed to take the first pictures of black holes (which they later indeed succeeded in doing).

That coffee break, however, was devoted to another newly discovered phenomenon in astronomy and hotly debated: “fast radio bursts”, or FRBs. He had never heard of them, Rezzolla said, when Falcke mentioned them to him. Falcke explained that they are short, one-off signals in a narrow frequency range, which radio telescopes occasionally receive. The fact that the signal’s higher frequencies arrive slightly before the lower ones indicated, Falcke continued, that they originate very far away and outside our galaxy. FRBs were first noticed in 2007 by Duncan Lorimer, a British astrophysicist, who interpreted them as real signals and not as interference, etc.

Artefacts from the microwave

Lorimer’s theory was slightly discredited, however, when it emerged that a number of the signals measured by an Australian radio telescope stemmed from microwave ovens at the visitor center where lunch was being heated up for guests. But because FRBs were also detected when the visitor center was closed, as well as by other radio telescopes, the question remained, said Falcke, of where they came from. While Falcke did not have any reasonable explanation, Rezzolla said that they could be neutron stars collapsing to black holes. “The explanation,” said Rezzolla, “is as follows: a black hole cannot have a magnetic field, while neutron stars are known to have very strong ones. When a neutron star collapses to a black hole, the magnetic field lines must break away and propagate through space as radio waves. Because the collapse of a neutron star lasts just a few milliseconds, only a short, one-off signal is produced.”

Rezzolla knew this would happen because shortly before the meeting in Bonn he had done some calculations for precisely this scenario in order to study the fate of the magnetic field of a collapsing neutron star. After the discussion, he and Falcke finalized the details and wrote a scientific paper in only one week. Finding a name for the phenomenon demanded considerably more time because they could not agree on the right one. This changed three weeks later, when Rezzolla was driving in the car with his wife, who warned him to slow down because of a speed trap: in German a “Blitzer”. That warning was the inspiration for the phenomenon’s present name: Blitzar – a flashing star! – in analogy with other fascinating names like pulsar.

Not disproved so far

The blitzar scenario has become one of the most popular explanations for FRBs, at least for those observed only once. “So far, no one has disproved the blitzar theory,” Rezzolla is pleased to say. “It is also clear that when neutron stars with a magnetic field slow down and gravitation takes over, they collapse to a black hole, for example immediately after a neutron star collision. In the process, they will emit a radio wave signal. There is no doubt whatsoever about that.”

Rezzolla is particularly proud of the blitzar theory because its development was quite accidental. He is convinced: “This is how ideas are born. By linking existing information and findings. Einstein did no differently. He used the differential geometry developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss, Bernhard Riemann and other mathematicians to explain gravitation.” The hope remains that Rezzolla and his colleagues will continue to find explanations for the secrets of our universe in many inspiring coffee breaks in the future.

They don’t come any denser than this: neutron stars and black holes

Neutron stars are probably – after black holes – the most compact objects in the Universe: in them, the mass of our Sun is compressed into a sphere with the diameter of a large city. They consist mainly of neutrons. Most neutron stars rotate at several hundred revolutions per second, have a tremendously strong magnetic field and emit an extremely powerful electromagnetic beam in the radio frequency range along both their north and south poles. The rotational axis of a neutron star mostly deviates from its magnetic axis, causing the electromagnetic beam to spin. This can be observed on Earth as rhythmic flickering or blinking, which is why such neutron stars, also known as pulsars (“pulsating stars”), are often popularly referred to as cosmic lighthouses.

A neutron star owes its formation to a huge stellar explosion, a supernova, of which it is the remnant. During the explosion, it might experience a recoil which will shoot it through space. If two neutron stars are in a binary system – and sufficiently close – they begin a deadly dance: they orbit each other in an increasingly narrow spiral, at the end of which the neutron stars collide and merge. As a result of the fusion, a more massive neutron star is produced, which will eventually collapse to a black hole. When neutron stars orbit each other and finally merge, gravitational waves are produced that are so powerful that they are still measurable millions of light years away on Earth.

A black hole is the most extreme example of spacetime curvature and can reach enormous masses. The black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, for example, has an incredible mass of 6.5 billion solar masses. Independent of its mass, the gravitational pull near a black hole is so strong that it is increasingly hard to escape as one gets closer. The boundary of the region where not even light can escape the gravitational pull of the black hole is referred to as the event horizon. In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, a global research team led by Luciano Rezzolla, among others, published the first image of a black hole. It shows the black hole’s shadow: a dark region surrounded by a ring of light that just manages to escape the black hole’s gravitational pull. What does the inside of a black hole look like? We don’t know. This is the point where even Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity reaches its limits: we do not have even a mathematical understanding of the very center of a black hole.

About

Luciano Rezzolla, born in 1967, earned his doctoral degree at the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati, Trieste, in the field of Relativistic Astrophysics, where, having spent time as a postdoctoral researcher, for instance in the USA, he became director of its computing center. From 2006 to 2014, he led the Numerical Relativity Group at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics before being appointed as Chair of Theoretical Astrophysics at Goethe University Frankfurt. He published the first images of black holes with the global Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) research collaboration in 2019 and 2022. Together with Nobert Pietralla (see p. 24), he is the spokesperson for the “ELEMENTS Research Cluster: Exploring the Universe from Microscopic to Macroscopic Scales”.

The author:

Dr. Markus Bernards, born in 1968, is a molecular biologist, science journalist and editor of Forschung Frankfurt.